When Stargate Infinity premiered on September 14, 2002, it was the first chance fans of Stargate SG-1 had to see how MGM planned to expand the franchise on TV. If those fans were hoping a Saturday morning kid’s show on Fox was going to give them more of the same, though, SGI’s short life suggests many were disappointed.

Set 30 years after the Stargate movie and bereft of anything familiar to fans aside from the titular portal, Stargate Infinity took place in a Stargate universe all of its own. It is no wonder the show is generally regarded as too far removed from the rest of the franchise to warrant more than an honorable mention. Still, every series has its story, and Stargate Infinity’s sounds like one of its great missed opportunities.

Speaking to The Companion, key people involved in making it remember a project that might have been more epic but for MGM’s disinterest, an inadequate budget, and a well-intentioned initiative by the US government.

As Told By

The Genesis of Stargate Infinity

Stargate Infinity had its origins at the confluence of production deals involving MGM, Fox, and at least two independent companies that supplied networks with programs. Ironically, though, it was probably Fox, not MGM, that set things in motion.

Early in 2002, Fox announced that it was outsourcing production of its Saturday morning kids’ shows to a third-party production company, 4Kids Entertainment. Starting with the 2002/2003 television season, the $100 million deal allowed 4Kids to lease a four-hour programming block on Fox, which it later named FoxBox, and fill that with programming.

According to the trade magazine Broadcasting & Cable, one of 4Kids’ competitors for the deal was animation studio DIC Entertainment. Although DIC lost out, 4Kids made its own deal with the cartoon maker to supply programming for FoxBox. The show they got was Stargate Infinity and they scheduled the premiere episode to kick off FoxBox as the first show in the block.

Stargate attracted the attention of DIC President Andy Heyward because the brand had an established fanbase, suggests Eric Lewald, DIC’s Executive in Charge of Story and Development on Stargate Infinity. Heyward was always hunting for “presold properties” because that made it easier for him to sell DIC series around the world, Lewald tells us. Moreover, MGM may have given DIC a license to make an animated Stargate show because the Hollywood studio couldn’t make it themselves.

“DIC, unlike major studios like Disney or Warner Brothers, didn’t have a huge library or the money to pay for name brands like famous movies,” Lewald says.

“MGM, the weakest major studio, didn’t have much of an animation division, so they seemed open to selling rights to some of their hit properties – RoboCop, Stargate, etc. – for the very small price that Andy could afford.”

Heyward was already an animation veteran by the time Stargate came onto his radar. After spending five years as a writer and story editor at Hanna-Barbera, he would become one of the most influential figures in American children’s television at DIC, producing a plethora of shows, including Inspector Gadget, The Real Ghostbusters, G.I. Joe, Dennis the Menace, and The Adventures of Sonic the Hedgehog.

As with many DIC shows, Heyward set up Stargate Infinity as a co-production between companies spread across the globe. According to the show’s end credits, Hong Ying Universe Company provided the animation. This Taiwanese company had worked on several American animated series, including other DIC co-productions, such as Sherlock Holmes in the 22nd Century. Meanwhile, the credits name Seahorse Productions and Studio 352 as suppliers of unspecified pre-production services. These two companies are linked by writer and producer Stephan Roelants. Roelants created Studio 352 in Luxembourg in 1997 and is named President and CEO of Seahorse in SGI’s credits.

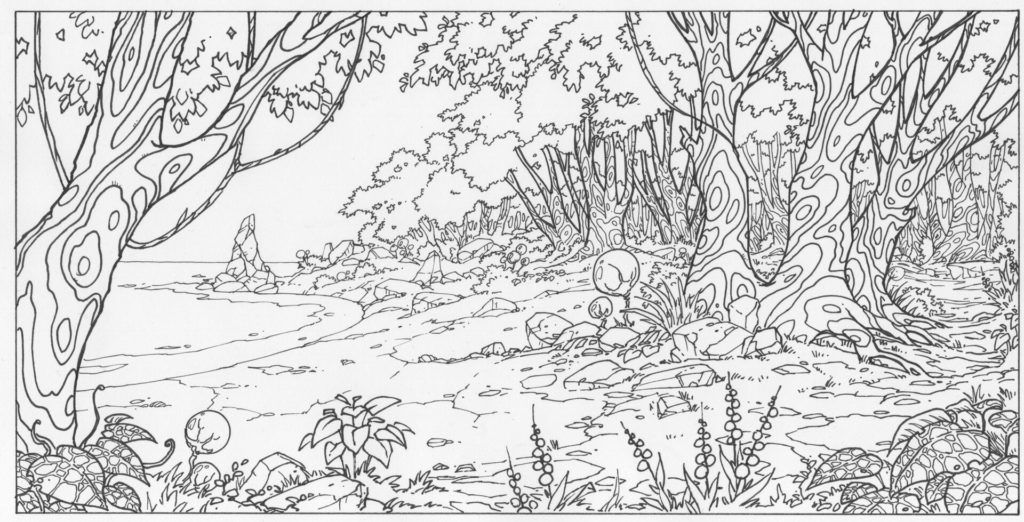

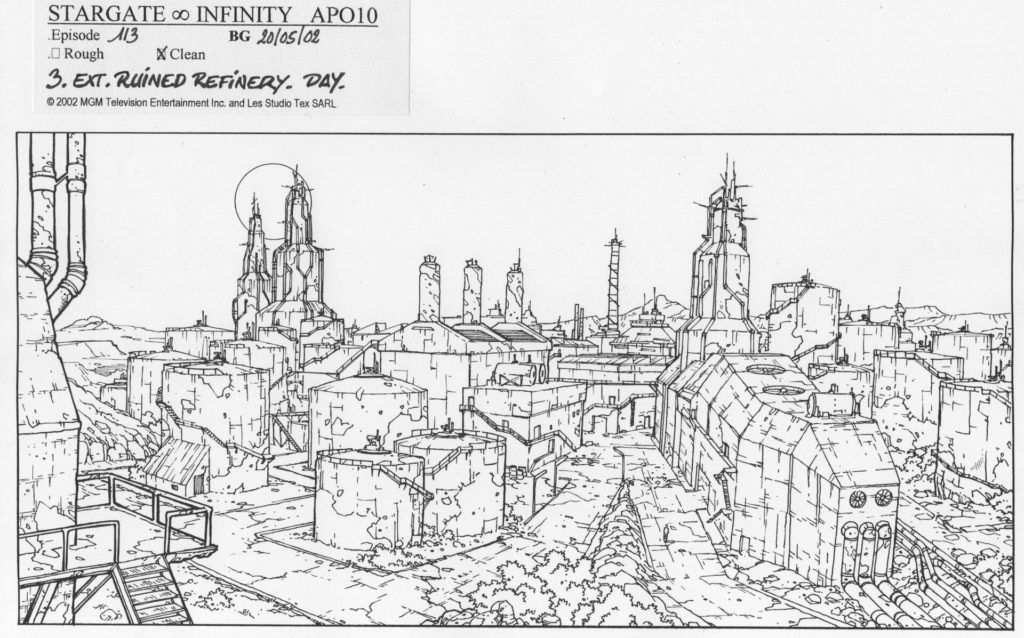

David Pellet, now art director on videogames like the Ghost Recon and Assassin’s Creed series for Ubisoft Bordeaux, offers some insight into his role as master background artist for the mysterious Seahorse Productions: “I produced master environment line art concepts from the script, for the storyboard and the layout teams. I worked at the Seahorse studio in Paris in 2001 for 13 weeks producing two episodes per week. I did almost 150 line art concepts on this project, ink on paper work – the traditional way!”

Seahorse was instrumental in getting the show off the ground creatively, as Pellet explains: “The studio role was to handle the artistic creation pre-production part: characters, creatures, environment, props, VFX, storyboard, and also all the 3D assets in the show. It was quite a lot, so maybe 80 artists in the studio worked on the project.”

DIC Entertainment’s co-production partner on Stargate Infinity was a company called Les Studios Tex SARL. Yet, LST’s contribution to SGI is unclear. Based in Paris, the company was named after cartoon legend Tex Avery and was launched by Heyward in 1997 with major investment from DIC. DIC was then owned by Disney but was originally an independent French company. Although LST was also an animation production studio and co-produced other shows with DIC, Lewald doesn’t recall it being responsible for anything in Stargate Infinity that appeared on screen.

“On SGI, we at DIC in California did the creative work,” Lewald explains. “There may have been some sort of financial connection with the French studio – I wasn’t involved in the business side of things – but they didn’t write or draw anything that I was aware of.”

LST’s role in Stargate Infinity may, indeed, have been business-related as the company would have facilitated access to the European market. Some European governments, including France, had instituted regulations and incentives to ensure their citizens watched at least some locally produced material. By the time SGI was made, DIC had split from Disney, but LST was still around to give Heyward a French connection he could leverage off.

“He took advantage of his European contacts to ‘presell’ series overseas,” Lewald says. “He would often make ‘co-productions’ with European studios, especially French ones because there were large subsidies available for series deemed to be a certain percentage ‘European content’ (creative staff), or ‘French content’. Canada had similar deals to get their people work, including some which allowed them to be counted in with Europeans.”

French funding sources that Heyward may have taken advantage of through LST include the Centre National de la Cinématographie (now the Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée), an agency of the French Ministry of Culture. Mandated with supporting French-made entertainment, the Centre’s name appears as a participant in the production of Stargate Infinity in the show’s end credits.

It wasn’t just overseas that Heyward could call up people he had previously relied on, though. The creative team at DIC’s offices in Burbank included a well-established group of production professionals that Heyward had worked with on other shows. These included Lewald and Heyward’s long-time associate Michael Maliani, who oversaw design and production at DIC.

“All of the artists worked for him,” Lewald explains. “He was the major creative force for DIC for 20 years. On most shows, Mike was hands-on in charge of developing, designing, and producing the series.”

Working alongside Maliani as story editors were brothers Michael and Mark Edward Edens. Mark remembers contributing outlines and a couple of scripts to Stargate Infinity but says his brother was more involved. Michael, on the other hand, recalls them working together on the show’s premise, which involved a group of heroes, mostly from Stargate Command, using the Stargates to evade a villainous lizard-like race called the Tlak’kahn.

“I worked with Mark to come up with the episodes and the general direction of the show,” Michael recalls. “We came up with the idea of having them being sent to an unknown area of space by a traitor at the main Stargate base. It was a way to get them lost and roaming from unknown Stargate to Stargate as the series progressed. It also explained why they couldn’t just go back – they had to discover who the traitor was.”

Building the World of Stargate Infinity

As a creative executive, Lewald worked closely with the Edens on Stargate Infinity’s series bible. Yet, neither Lewald nor Michael Edens recalls MGM having much to say about what they were doing with the Stargate concept. Once Heyward had signed the deal with MGM, the Hollywood studio made a few suggestions but otherwise mostly left Heyward’s team to it, Lewald says. One exception was the name, Stargate Infinity, which probably came from higher up the chain of command.

“Andy was always intensely concerned with marketing decisions like series titles, and I’m sure MGM had a veto over any names they didn’t like,” Lewald says.

Michael Edens remembers only one meeting with MGM and his recollection shows that the studio intended to further expand the Stargate franchise. Yet, as Michael remembers it, Stargate Infinity wasn’t in those plans as MGM did little to insist on continuity with Stargate SG-1 or the spinoff they were working on.

“Other than the one meeting with the MGM executives, where they discussed a couple of plotlines they were going to use in Stargate Atlantis, which we were warned to stay away from, we didn’t have much direction,” he tells us. “Since we were set in the future of the Stargate franchise, we were given free rein to do what we wanted.”

In an ideal world, the writers might have familiarized themselves with what had come before to avoid digressing too far from canon. They had all seen the feature film, Lewald says, and Michael Edens recalls having seen a few episodes of Stargate SG-1. But MGM seemed happy to let them run with their interpretation, and no one at DIC had time to watch the 100 or so episodes of SG-1 that had already aired. DIC had a busy production schedule, and it was all the writers could do to keep up with that because they were often working on more than one show.

“It was definitely typical to work on multiple shows at once,” says Kaaren Lee Brown, who as DIC Vice President was also part of the team that developed Stargate Infinity. “I managed with abundant amounts of coffee and an amazing team of in-house creatives and freelancers.”

Among the DIC shows that Lewald and the Edens worked on before SGI were several that were targeted at a relatively mature child audience. One example was X-Men: The Animated Series, which ran from 1992 to 1997. X-Men got high ratings and positive reviews from critics and fans for its intelligent, involving storylines. When DIC tasked several X-Men personnel with developing Stargate Infinity, the team wanted to use the same approach.

“Mark and Michael and I had done the five-part ‘The Phoenix Saga’, a space epic, for the X-Men animated series in the mid-‘90s,” Lewald says. “Will Meugniot, our SGI director, had designed the X-Men series. We all were imagining something of that scope.”

Mark Edward Edens tells a similar story:

“Eric Lewald, Michael, and I had all been involved with the X-Men animated series and similar relatively adult-themed action-adventure projects, like Exosquad and Wing Commander Academy. We would have done Stargate Infinity in a similar vein, as basically an animated sci-fi series for general audiences, with some simplification and toned-down violence to make it more kid-friendly, but otherwise doing the same stories you’d do in a live-action series.”

The writers sought to achieve that kid-friendly tone by using characters who would appeal to an “older boy demographic,” as Mark Edward Edens describes it. Except for SGC veteran and square-jawed team leader Gus Bonner, most were therefore young adults.

“Animated shows were always using heroes from ‘academies’ as a way to get ‘relatable’ young characters involved in the kind of dangerous action that no responsible adult would normally let a child anywhere near,” Mark remembers.

To voice these characters, Heyward may have taken advantage of the Canadian incentives Lewald previously alluded to as Stargate Infinity’s cast included several actors from that country. Among these was Dale Wilson, whose deep voice gave Bonner his commanding presence. A few months after SGI premiered, Wilson would have a small role in the Stargate SG-1 episode ‘Smoke & Mirrors’ (S6, Ep14).

Other regular characters in Stargate Infinity included Bonner’s niece, Stacey, played by Tifanie Christun, R.J. Harrison a cocky, young human recruit voiced by Mark Hildreth, Ec’co, a hybrid between a human and an alien race called the Hrathi, played by Cusse Mankuma, and Draga, a powerful winged female character voiced by Kathleen Barr. The Tlak’kahn want Draga because they believe her to be an Ancient. This implied uncertainty about the appearance of Ancients in Stargate Infinity is one of the show’s most significant inconsistencies with official canon as the live-action series would establish different lore around the gate builders.

Like Star Trek: Voyager, Stargate Infinity also included a Native American character – although unlike Star Trek: Voyager, the actor had First Nations heritage. Her name was Seattle Montoya, and she was performed by American voice artist, singer, and presenter Bettina Bush. Bush’s credits go back to the 1980s when, as a kid, she was the voice of Rainbow Brite in the show of that name, Megan on My Little Pony ‘n Friends, and Lucy Little on The Littles. Bush says playing Montoya excited her because they shared a personal connection and she rarely got to play Native American characters on screen.

“I dug her because I had been in a film when I was 15 called Journey to Spirit Island,” says Bush. “I played a Native American girl, and I am part Native American. Filming that movie kind of immersed me in the Native American culture and so I did a lot of charity work on reservations and a lot of speaking to Native American kids. That never stopped, I just always continued doing it. So, when I got this character, I was like, ‘Wow, I’ve never actually had the opportunity to voice a Native American animated character in my 20-year career.’”

When Stargate Infinity was cast, Bush also had the advantage of being well-known to Heyward and good friends with DIC’s Casting Director, Marsha Goodman. It also helped that Montoya and Bush had similar features, the actress explains.

“Every Christmas time I would go visit Marsha Goodman at DIC and I would bring her cookies and we would go to lunch. We just always stayed friends… When she was starting Infinity, she called me and said, ‘You know, it’s so funny because everybody in the office sees the Seattle character and they’re like, ‘Oh is that Bettina?’ because she looks just like me. They didn’t even bother to audition anybody. Everybody in the office would see this picture and they were like, ‘Oh, they clearly drew that with Bettina in mind.’”

In addition to her impressive voice acting credits, Bush is now recognized as a mentor for working mothers. Consistent with these values, Montoya’s character appealed to Bush because she was a female role model with talents that made her as strong as the male characters in the show.

“Seattle was a welcome breath of fresh air,” Bush remembers. “I love that she had the psychic ability, she had these visions. I thought that was super cool. And I thought that the show was really intelligently written. I really enjoyed it. I thought it was great… I loved how intuitive she was. I loved that she was not afraid to speak her mind. There was a lot of standing up for what she believed in inherent in the character. She had kind of a core strength that was not necessarily always present in the female characters. Nobody was going to boss her around and I loved that about the character.”

With her diverse heritage, Bush has also become an advocate of multiculturalism. Accordingly, she praises Stargate Infinity for having underlying themes that promote discovery and interracial understanding.

“I loved the fact that part of the show was the [characters] immersing themselves in a new culture and having to learn and appreciate a new culture before they could move on,” she says. “I thought that was brilliant and it’s one of the reasons I’m very proud of that show. I feel as though what it was teaching was acceptance and celebrating diversity. That was not a lesson that was being taught very heavily during that timeframe, and it needed to be. So, I thought it was fantastic the way that they did that. There was biodiversity as well as cultural diversity that was emphasized, which I thought was extremely cool.”

Stargate Infinity’s Moral Message

The positive messaging Bush refers to was not just a side-effect of stories involving heroes who frequently meet new races. Since the US Government passed the 1990 Children’s Television Act, which is enforced by the Federal Communications Commission, TV networks have been required to provide programming “that furthers the positive development of children 16 years of age and under.” This ‘pro-social’ policy was implemented to make networks provide more “educational and informational” TV shows for children while promoting socially desirable behavior, such as altruism, friendship, helpfulness, and self-control.

The Act was revised in 1997 to make broadcast stations dedicate at least 15 percent of their daily airtime to “educational, value-laden and age-appropriate” children’s shows. Under these stricter regulations, several networks decided to air pro-social material on Saturday mornings. On Fox, this was Stargate Infinity because DIC’s deal with 4Kids was specifically to supply a half-hour of educational programming that met FCC requirements.

“For a time, Andy had a deal to provide ‘educational content’ to network TV,” Lewald explains. “We had to have a child psychologist – nice enough gentleman – okay every idea and then every script to show that every episode was in fact a learning tool for small children.”

The lessons the writers hoped to leave kids with included “don’t be afraid of, or look down on, people because their traditions and customs are different from yours,” Michael Edens recalls. Still, while the policy objectives were commendable, having every script reviewed for content was a headache for the writers. Furthermore, each episode’s “life lessons” had to be obvious to children of an age where make-believe would appeal more than moral dilemmas. The result might not have been what existing fans of the franchise wanted but it was unavoidable, Lewald admits.

“Stargate the movie is pure action-adventure storytelling – something glorious and valuable when done right,” he says.

“Having to shoehorn 26 ‘age-appropriate lessons’ into what fans expected to be a spin-off of a PG-13-rated, grand adventure movie was an unfortunate condition of being able to do the project at all. In effect, we had to pretend we were teaching life lessons to second graders.”

Mark Edward Edens goes further, suggesting that the requirement to provide pro-social content damaged the show:

“Instead of exploring strange alien worlds and fighting for survival, our heroes were shoe-horned into situations in which they learned valuable life lessons and educational content suitable for pre-adolescents. The result was an anemic action show that alienated Stargate fans.”

Ultimately, though, it may not have just been the compromises the writers made that hurt the finished product. According to Lewald, their ambitions for a series that had the content and scope to appeal to a broad audience had to be watered down because there wasn’t enough money to realize that vision.

“While we wrote with an Imax screen image of action in our heads, what DIC paid to produce was something iPad-sized,” says Lewald. “The writing budget was fine – it was the production/animation budget that was a problem. We writers, in crafting the stories, were imagining Stargate-like spectacle, or at least like animated series we’d done like X-Men. But Mike [Maliani] and the overseas animators were given maybe 30 percent of the time and money to do it. If we’d known beforehand, we might have written simpler, smaller stories.”

Perhaps it was predictable under these circumstances that Stargate Infinity had only one season. After DIC had completed the contract for 26 episodes, the writers didn’t expect to do more, Lewald explains. “At this level of production, unless a series is a breakout hit, often the financing is only there for the initial order.”

Naturally, this left room for regret among Stargate Infinity alumni who believe the show could have expanded Stargate’s fanbase instead of causing those who already knew the franchise to change channels.

“One thing we showed with X-Men is that you can do a show that satisfies fans of an original property and still appeals to kids seeing the franchise for the first time,” says Mark Edward Edens.

“Stargate Infinity was kind of a lesson in how to waste a property’s popularity by ignoring what fans liked about it.”

Even so, it would be unfair to give the impression that Stargate Infinity didn’t please anyone. Bettina Bush recalls getting mail from happy viewers and our interview brings back a fond memory of one particular fan.

“I do remember at that time there being an influx of fan mail from Stargate fans, and it was all positive,” she says. “Oh, my gosh, you just totally sparked something. I remember a girl had somehow obtained some kind of coloring page of my character and she had colored it herself and asked me to sign it and I did. I don’t know where that is now.”

On this positive note, it is fitting to give the last word to Michael Edens, who sadly passed away in 2021 a few months after we interviewed him for this article. When reflecting on Stargate Infinity, Michael expresses measured satisfaction about the finished product and believes viewers should judge the series on its own merits.

“I didn’t think it was as bad as hardcore Stargate fans say,” he tells us. “It was different, but it was a different medium – animation – aimed at a different audience, the eight-year-old and older crowd. Since we were set in the Stargate future, we thought the original fans would cut us some slack, but apparently, they didn’t. We did the best we could do, especially since we were out there operating on our own with very little input from MGM, so the fan reaction came as something of a surprise. It’s maybe not my best work, like X-Men or Exosquad, but I don’t think it’s anything to be ashamed of. If you just watch it for what it is, it’s a pretty entertaining show.”

Dedication

This article is dedicated to the memory of Michael Lynn Edens, who passed away in Kentucky on May 7, 2021, at the age of 69. Aside from Stargate Infinity, other animated shows he worked on include Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Exosquad, X-Men: The Animated Series, Wing Commander Academy, and RoboCop: Alpha Commando. As a writer and editor for DIC, he was respected by his colleagues and was remembered as a pleasure to work with.

When we interviewed Eric Lewald before Michael passed away and asked him what he enjoyed about working on Stargate Infinity, Lewald said, “Mark and Michael Edens are old friends of mine. Writing with them is always fun.”

This article was first published on April 20th, 2022, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂