Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) enters the scene in all leather, an indication of how The Matrix will go. Already, the 1999 film pushes back against what female protagonists were expected to be during that time: beautifully charming homecoming queens in The Breakfast Club (1985), and bubbly blonde cheerleaders in Bring it On (2000).

In grittier films, such as Pulp Fiction (1994) or Basic Instinct (1992), female leads were slanted in the male gaze, created to fight crime and dabble in backdoor drug deals while being sexually appealing in slinky outfits. The ’90s offered a prototype of what strong women were, long-haired, curvy actresses that were approachable but intimidating all at once. With one image of femininity being pushed, it felt hard to know where I fit in.

Growing up, the idealized woman never matched my self-image.

When The Matrix came out, all I knew about gender was that I didn’t want to be a “girly girl.” My limited eleven-year knowledge correlated “girly girl” to everything I hated about being a woman: dresses, fuzzy pens, and being excluded on the playground when it was time for boys to pick their soccer team. Tomboy was a status I desired, a rejection of “woman” for a young, highly confused third grader. This wasn’t a deviation from the norm, most people in my grade also loved leaning into tomboy but being branded a “girly girl” seemed a death note, an acceptance of being weaker than the boys in my grade. I had a nasty bowl cut, basketball shorts, and high, white socks, the epitome of toting the line between man and woman.

Of course, I didn’t have the tools to psychoanalyze my existence this deep at the time, but now, as a 27-year-old far removed from the pain of my youth, I consider this to be a good summary of my struggle with gender growing up.

Gender on the Big Screen

Drawing inspiration on what made a “good woman” in the early 21st century was hard, considering how small the pool of representation was in mainstream media. Rolling into the 21st century, male directors, producers, and actors dominated Hollywood. Little female representation existed behind the scenes, resulting in a distorted image of female representation on screen, where women lived up to men’s expectations at the expense of themselves. Especially in the ’90s, when media streaming and downloadable content increased the number of movies produced, female visibility faced a sharp decrease on-screen.

Per the study Sexism on the Silver Screen: Exploring Film’s Gender Divide, the proportion of movies starring female characters fell 55% between 2005 and 2009, from a record high of 17,403 movies in 2005 to 7,884 movies in 2009. In terms of relative proportions, males held between 72% and 84% of leading roles between 2000 and 2009. Hollywood saw a rise and fall of women in films, remaining stagnant in expanding female representation. It’s a narrative we hear all too often, Hollywood is a man’s world with women at the fringes.

And it wasn’t simply in movies, either.

The Transformation of Gender in English-Language Fiction, published in the journal Cultural Analytics found that the presentation of gender was a paradox in the 20th century. As rigid gender roles dissipated in literature and film, indicating more equality between sexes, the number of women characters, and the proportion of women authors, decreased. The further mainstream media moved away from what it had constructed to be traditional femininity, i.e. wives scrubbing the kitchen waiting for their husbands to come home à la the 1950s, the fewer people seemed to understand how to present women.

Then came the Wachowskis.

The Roots of Carrie Anne Moss’s Trinity

When Trinity came on screen, she was unlike anyone I had ever seen. Maybe it was the pure shock of seeing a hot woman with incredibly short hair (unheard of in grade school) or maybe it was the fact Trinity defied what I expected a woman to be but for the first time, I felt an incredible draw to what I wanted to emulate in life. Unlike the 2003 Daredevil, a film I was also obsessed with at the time, her leather outfit never felt intended to grab men’s attention the way Jennifer Garner’s did. This point was only strengthened when every member of Nebuchadnezzar, the hovercraft captained by Morpheus, also donned the same leather ensemble when operating within the real world. They were equal, not separated by binary, and the charge felt spearheaded by Trinity.

Spearheaded by nonbinary icons that paved the pathway before her.

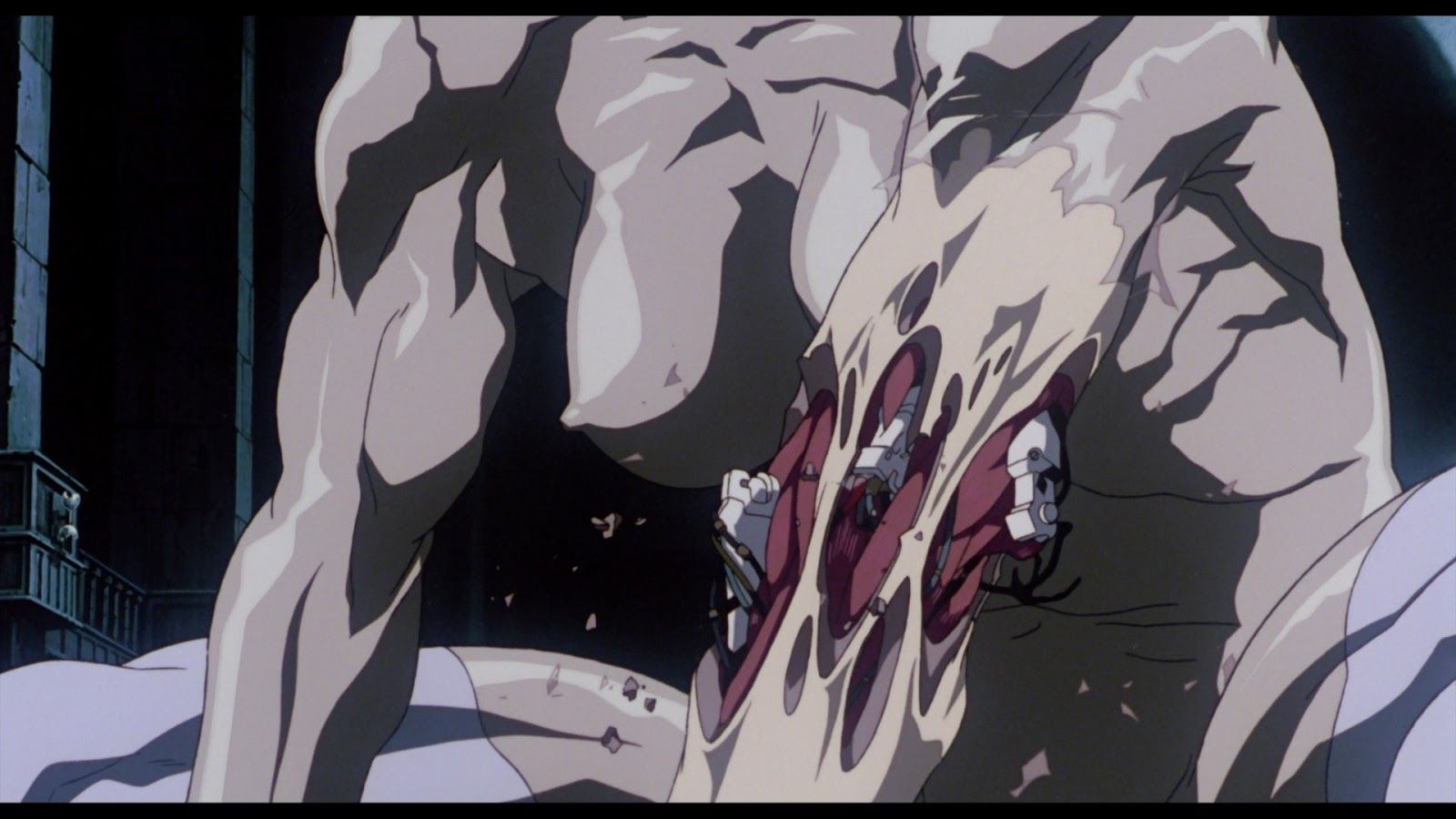

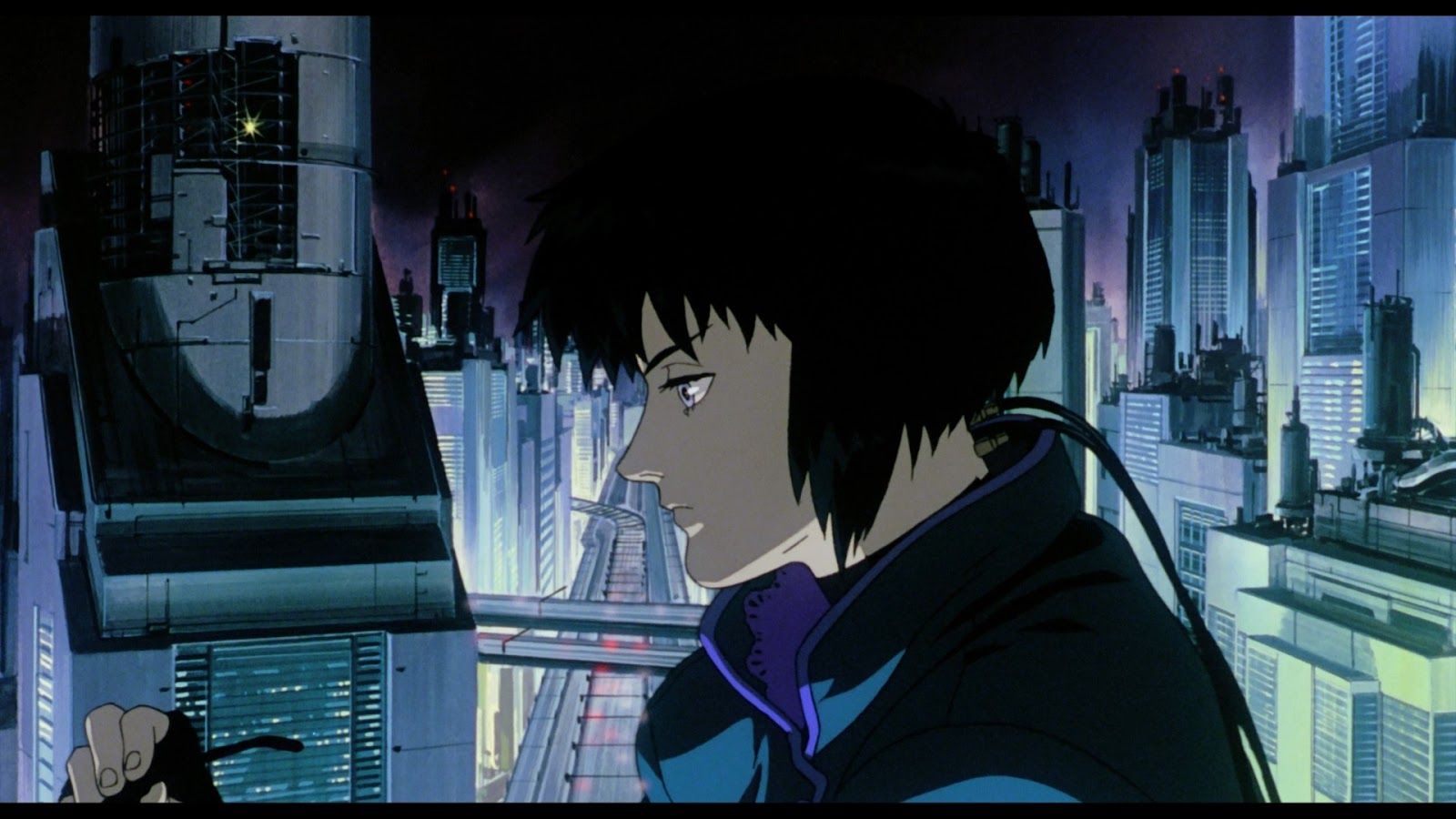

According to the Wachowskis, a big part of The Matrix was inspired by the 1995 Japanese cyberpunk anime Ghost in the Shell. Based on the manga series of the same name, Ghost in the Shell follows Major Motoko Kusanagi on their quest to stop a cybernetic terrorist from infiltrating various networks. As confusing as The Matrix, this cyberpunk dystopia features computer technology that has advanced to the point that many citizens have cyber brains, technology that lets them plug in their brains with various networks. Essentially, people are now able to import themselves into the worldwide web and explore it as if they are Wreck-it Ralph (2012) experiencing Wi-Fi for the first time.

If you need to visualize most scenes in Ghost in the Shell, this is likely the easiest way to describe it.

I initially watched Ghost in the Shell as a means to impress a boy (embarrassing) whose virginity I’d later take (impressive). Similar to grade school, high school was a time of feeling disconnect lingering below the surface, growing larger and inexplicable the more I watched films where people toted the line between gender neutrality. By the time 2011 rolled around when I first watched Ghost in the Shell, I had expanded my palate to include more media that fed whatever feelings made me uncomfortable in my body. I wanted to get out constantly, going to extremes to reshape and repurpose how I saw myself, putting my body through pain for the pain it gave me.

Why love something that brought so much confusion to me?

Movies with strong female protagonists that didn’t necessarily present as what translated to woman in my head, the best example being Amanda Bynes in She’s the Man (2006), and movies that dealt with body as an entity outside of self, like with body horror in the Jackass franchises. I couldn’t possibly process the plot of the film but loved the fact Major Kusanagi existed outside her body, a cyborg hosting a brain incredibly powerful and strong.

How I could translate this analysis of the film to my crush was a moot point.

The Female Body as a Tool

This focus on female body as nothing but a holding cell is most present in Major Kusanagi than Trinity. Despite Trinity being what one might consider the human replica of Kusanagi’s character, The Matrix allows limited room for manipulation of body than Ghost in the Shell can, given the fact it is animated. At the end of the film, Kusanagi, after one and a half hours of exploring what it even means to be human, merges with the main antagonist of the film Puppet Master, a hacker who seems to be an all-powerful benevolent God. In one move, she abandons her body completely, elevating her intelligence for the sake of giving up her being. The end, after posing many philosophical questions, sends the message that we are truly more than the vessel we inhabit, more than societal norms have conditioned us to be.