Martial arts have been infiltrating Hollywood cinema since it began, whether it’s Charlie Chaplin kicking a bully up the backside or James Cagney training in judo for a fight scene in Frank Lloyd’s 1945 drama Blood on the Sun. But the genre will always be associated with the Golden Age of Hong Kong cinema, that being everything from King Hu’s wuxia classic Come Drink with Me (1966) right up until Jackie Chan hit the mainstream with Drunken Master (1978).

It’s no coincidence that, if you watch the credits, you’ll see the same names pop up time and again. The industry was much smaller then, and films were churned out like a production line. This meant that the same people were recruited to arrange the action, and one name that is now synonymous with quality fight sequences is director Yuen Woo-Ping.

All this brings us to The Matrix (1999), a film that is responsible for a thousand parodies of that slo-mo scene. But it wasn’t just the effects that were revolutionary. When the Wachowskis hired Yuen to direct and choreograph the action sequences, they were also imbuing the film with his wealth of expertise and experience in filming action. And that is the most important element because, prior to this, many Hollywood filmmakers had little understanding of how to film fight sequences in a way that was coherent and easy to follow as well as being dynamic and kinetic. Look at the vast majority of Hollywood fight scenes, you’ll see that their emphasis is on brute strength and brawn. Schwarzenegger, John Wayne, and his roundhouse punches.

Speaking around the time of the risible sequel The Matrix Reloaded (2003), Yuen recalled:

“Before shooting The Matrix, the [Wachowskis] watched lots of Hong Kong movies, in order to look for someone who suited their style and they found me. This doesn’t imply that that the others were not good; it was because my style was more in tune with their ideas.”

It’s not just that Yuen choreographed a series of intricate fight sequences for The Matrix. The Hong Kong style was woven into the fabric of the film. Neo’s journey from idealistic young upstart to hero mirrors a multitude of martial arts films from Hong Kong’s Golden Era, perhaps most notably Yuen’s own Drunken Master. An immature man (Jackie Chan’s Wong Fei-hung) is brought sharply into focus by a wizened old martial arts master (Yuen Siu-Tin’s Beggar So).

Introducing Wuxia and the Hong Kong Method

Although The Matrix may have been groundbreaking in Hollywood, its origins, at least from a structural standpoint, go back to the very beginnings of Hong Kong cinema. Wuxia is a genre that has been popular with Chinese audiences since the invention of film – stories of melodrama, oppressed heroes, and balletic, as opposed to bone-crunching, fight sequences, usually involving swordplay. Literally meaning ‘sword fighting’, the wuxia genre draws on China’s rich cultural history to tell tales of good vs evil, often with archetypes rather than full-blooded characters. Wong Fei-hung, for example, is a hero of Chinese folklore whose identity is so intertwined with that of his film counterpart he has become a kind of shorthand when talking about a certain type of hero – that is, strong, stoic, and silent, always standing up for the little man or woman.

The late Kwan Tak-hing is most closely associated with the role, to this day holding the record as the longest-serving actor playing a single character, appearing in over a hundred films as the character in 32 years between 1949 and 1981. So synonymous was he with the role, that audiences would only accept another actor – like Jackie Chan in Drunken Master – if he was explicitly playing the character in his youth.

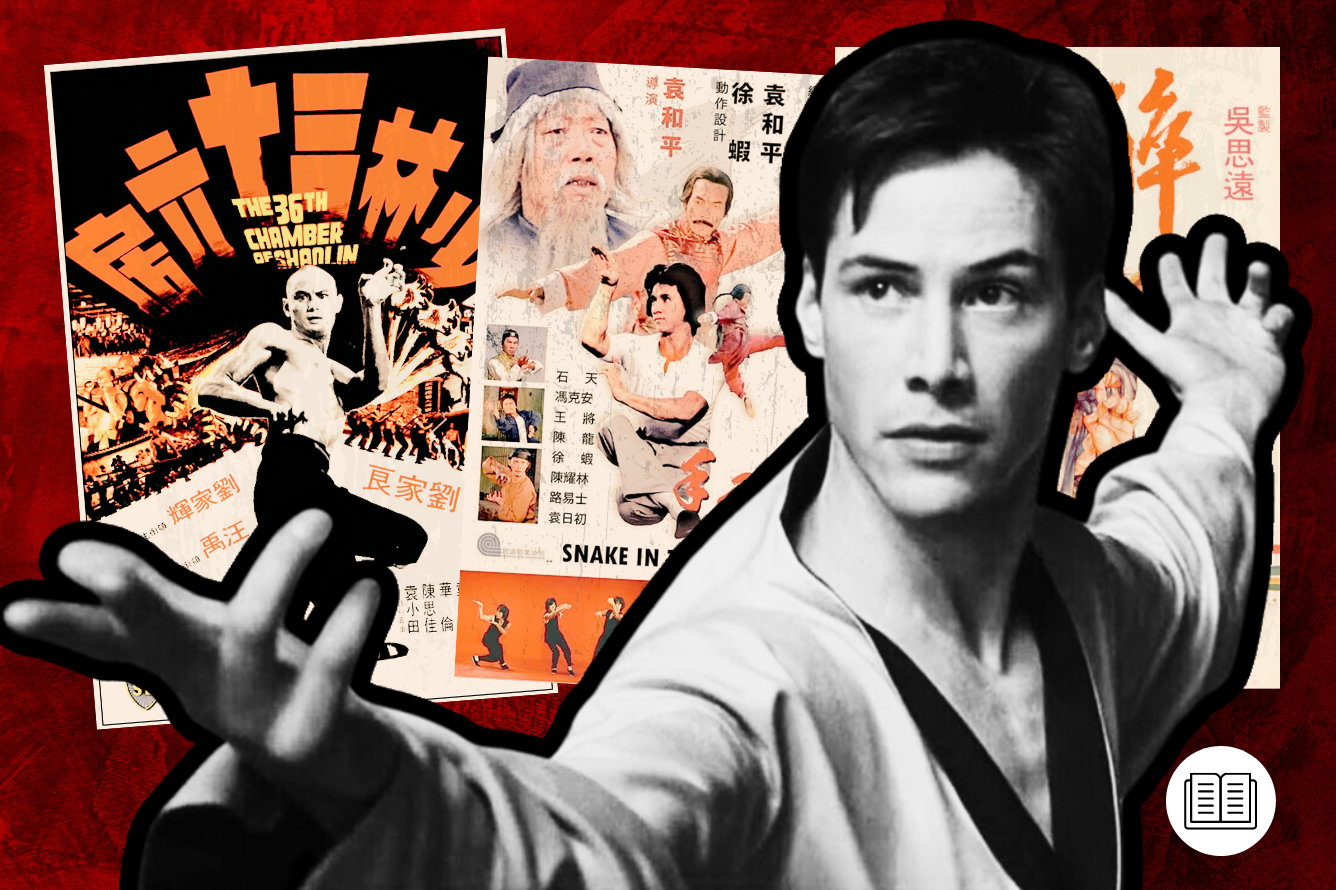

Yuen Woo-ping grew up in these productions, often working alongside his father, Yuen Siu-tien, himself a legend of Hong Kong cinema. A veteran of the Wong Fei Hung films, Tien was often responsible for choreographing and stunt doubling in the fight scenes and would achieve international stardom in his later years for playing Jackie Chan’s sozzled sifu in Snake in The Eagle’s Shadow (1978) and Drunken Master, both of which Yuen Woo-ping directed, and which have come to be regarded as classics of the genre.

It is difficult to understand the Hong Kong method without first knowing the lengths to which individual performers go to achieve peak fitness in their prime. Yuen grew up in a culture where many young children were sent to notoriously demanding Peking Opera Schools – part stage school, part boot camp where martial arts and acrobatics were as big a part of the curriculum as song and dance. Yuen attended Yu Jim-yuen’s China Drama Academy, as did Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, and Yuen Biao, the iconic triumvirate of ’80s Hong Kong action cinema. It wasn’t just something you did to train and enrich your life – it was your life.

From dawn to dusk, children would undergo training methods that today would be illegal, but then were simply par for the course. Hours spent punching, kicking, squatting in the unimaginably painful ‘horse stance’ (imagine a sitting position, your back perfectly straight but you are on your feet, often for hours) and made to do whatever their sifu demanded. Those methods may be unimaginable to the modern eye, but like them or loathe them it was these brutal practices that produced the greatest action directors in film history.

Yuen started working alongside his father, which was where he developed his keenly attuned eye not just for choreography, but camera movement and physical geography. What many prospective directors fail to understand, especially when it comes to action sequences, is that there is a rhythm. Jackie Chan put it best when he said that you don’t know the rhythm’s there until it’s not there. As you watch more Hong Kong films, you begin to understand what they are talking about.

“What was to be learned,” Yuen told Kung Fu Magazine, “was the movie language, the camera positions, the character personality, and how the chemistry of two people in terms of the fighting styles would mingle together. That's not teachable, that’s something you have to watch.”

The first thing you notice is that, unlike Hollywood action films, the takes in Hong Kong films are long.

Very long.

Applying the Hong Kong Method to The Matrix

If you ever have the inclination, find a classic Hong Kong fight sequence on YouTube and time the length of some of the shots. To put it in context, most Hollywood action will cut in under two seconds, often even more than that (I refer you to the now infamous clip from Olivier Megaton’s Taken 3, in which a sequence showing Liam Neeson jumping over a fence cuts 14 times in six seconds). This is allegedly to make the scene punchy, giving it pace. The reality is usually that the director is having to cut around stunt doubles, often shooting them from behind and cutting before we can see their face. In Hong Kong productions, this isn’t a problem because the actors are the stunt performers. This means that in any given shot, two martial artists could exchange anywhere from five to 20 blows, remembering complex choreography and performing it to perfection each time.

The second thing you notice is that the blows many of these performers take are brutal. And I’m not talking about the odd bruise, I’m talking about performers doing take after take being slammed into metal railings, kicked in the face, slamming onto hard floors, and smashing through glass. Of course, there are the tricks of the trade to help them (at this point I must recommend the superlative 1999 documentary Jackie Chan: My Stunts if you want to know more about this), but by and large, they are taking the knocks for real.

So where does this all tie in to The Matrix? Well, when The Wachowskis first conceived the idea for the film, they wanted to draw extensively not only on Hong Kong storytelling but the Hong Kong filmmaking method – so they went straight to the source. They tracked down Yuen and flew him to America, where they pitched him the story. Initially, Yuen was hesitant, because a story on this scale, which this budget, was something new and there was a lot of risk.

Speaking around the time of The Matrix Reloaded (2003), he said:

“Although the movements in science fiction need not belong to any specific sects or styles, they basically need to carry the notions of action. To choreograph The Matrix, I let go of Eastern, Western styles of fighting. What I sought for was realism in the fights, eliminating decorative movements – this is the contemporary fighting style. When two persons fight, it’s one punch followed by another continuously, no swerving of the body after every blow.”

His main concern, though, involved the actors. Yuen knew that to do justice to Neo’s story, Keanu Reeves would have to perform the fight sequences himself. Indeed, it was an intrinsic ingredient of his’s character’s arc, and in many ways, Keanu’s journey during production mirrored that of Neo’s. Yuen was surprised at how unfit the actors were and immediately started them on a rigorous training scheme.

“How do you tell an actor that they're going to have to spend four months training and learning kung-fu when they could make another movie in that same time?” the Wachowskis told Kung Fu Magazine.

“That’s what impressed us about Keanu. He understood why it was necessary and the dedication it required. In fact, the whole cast has amazed us with their dedication to the training regime – it‘s been incredibly rigorous.”

For months on end, the actors endured pain they never imagined as they discovered what it takes to be a top-level stunt performer. Nowadays it is commonplace to see actors boasting about doing their own stunts. But back then, aside perhaps from Jackie Chan, very few film stars took the risk, not least because any injuries would have meant shutting production down and putting people out of work. It’s common sense apart from anything else. Keanu in particular took to stunt performing, forming a close bond with his stunt double Chad Stahelski, who not only doubled for some of the more complex shots but also became stunt coordinator on the sequels and went on to direct John Wick (2014).

What is it about Yuen’s choreography that makes it stand out? A punch is a punch and a kick is a kick, right? Well, aside from the aforementioned rhythm and editing techniques, there is an undeniable beauty to his fights that are quite unlike anybody else. Just as John Woo’s films are often described as a ballet of bullets, Yuen’s action scenes are similarly fluid, literally in the case of The Matrix where many of the scenes required actors to be attached to wires, a process that later became known as ‘wire fu’. Yuen would take this technique to further heights, literally, when he designed the action for the Oscar-winning Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) the following year.

The Hero’s Journey in Wuxia and The Matrix

The other link to martial arts cinema, aside from the martial arts themselves, is more intrinsic. Baked into the story itself, the Wachowskis drew upon the long lineage of Hong Kong cinema to create their template for what would become The Matrix, beginning with Neo himself. The archetypal hero, The Wachowskis, for all their genre-smashing inventiveness, was surprisingly traditional when it came to creating the characters.

Neo can be discussed alongside the likes of Gordon Liu in The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978) or Wong Fei-hung from Drunken Master, that is, an underdog, a shorthand for gaining the sympathy of an audience. To draw upon film theory for a moment, the structure of The Matrix is as tight as a drum and conforms almost beat for beat to Joseph Campbell’s ‘Hero’s Journey’, a systemic approach that can also be applied to the protagonists of the vast majority of martial arts films. For simplicity, the basic elements of the Hero’s Journey are thus:

- The Call To Adventure and The Refusal Of The Call

Neo is, or at least he thinks he is, an ordinary hacker. When Morpheus shows him the truth, he is aghast and refuses to believe.

2. Crossing The First Threshold – Test, Allies, and Enemies

It is at this point that Neo meets the people who will become his closest allies throughout the story, and also when Morpheus begins his training, thus his evolution can begin, but first, he has to face his first challenge, here represented by Hugo Weaving’s Agent Smith.

3. The Road Back, Resurrection, and Return With The Elixir

Essentially act three. This is where Neo is forced into action to save Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne) and must confront the ultimate obstacle, in this case by fighting Agent Smith in the subway, before he can attain enlightenment, as it were, and become the hero of his own story.

Look at the plot of the standard martial arts picture, and you will see that the protagonist will go through the same journey, although it is especially prevalent in sifu/student films like Yuen’s own directorial debut Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow, to the extent that there are entire scenes and story beats that could be played side by side One such scene is the dojo fight, in which the sifu humiliates his student and shatters his ego, which he must do before Neo can reach his full potential. Yuen Siu-tien does the same with Jackie Chan in Snake… and Drunken Master, though of course those scenes are played much more for laughs.

Hing Kong Cinema’s Influence on Hollywood

In many ways, The Matrix is the perfect coalescence of East and West, and although Yuen may have choreographed more complex fight sequences in his earlier films (anybody who hasn’t seen his 1979 Sammo Hung vehicle The Magnificent Butcher is missing out on an absolute feast of frenzied fighting) when The Matrix was unleashed upon the world in 1999 it stunned Western audiences. John Woo brought Hollywood the forgettable Broken Arrow (1996) and Hard Target (1993), a Van Damme vehicle that, while there was a lot of impressive action, failed to stick in the memory. Face/Off (1997), meanwhile, failed to live up to what was admittedly a fantastic premise. Jackie Chan had just hit big with Rush Hour (1998), a heavily sanitized version of his Hong Kong schtick, but it wasn’t until Yuen unleashed his brand of fantastical fisticuffs that America and the world at large could really understand what Hong Kong action cinema was about.

John Woo would eventually break through in Hollywood the following year when he directed Tom Cruise in Mission: Impossible II (2000), but his influence was felt to arguably greater effect in The Matrix as well courtesy of his frantic, slow-mo-laden style of gunfighting dubbed ‘gun-fu’ – but that’s a story for a later article.

The legacy of The Matrix is still being felt to this day. A slew of early noughties action films tried to ape the style, which in turn gave work to a plethora of performers and choreographers from Hong Kong. Prime examples of this are McG’s Charlie’s Angels films (2000, 2003), which made use not only of another Yuen in Woo-ping’s elder brother Yuen Cheung-yan but also copied The Matrix’s bullet-time technique, to much lesser effect. It even made its way into Hollywood comedies, with the Scary Movie franchise frequently taking aim at the film’s propensity for pomposity, as well as using the slow-motion technique in order to mock it.

Keanu Reeves, meanwhile, has become something of a doyen of mainstream action pictures. After a career lull in the mid-2000s, he reteamed with Chad Stahelski for an extraordinary comeback as the titular character in John Wick. Utilizing every skill they acquired from The Matrix, Stahelski, and Reeves made a Hollywood action film on their terms – and were richly rewarded for it. Training extensively with Stahelski’s stunt team Alpha Stunts, they set a new standard in screen action, employing the gunplay of a classic Western and coalescing it with Eastern martial arts techniques and gun-fu. Reeves also took his love of stunt work to its natural conclusion when he made his directorial debut with Man of Tai Chi (2013), which showed his considerable prowess not only in front of the camera as the principal antagonist but in staging combat sequences with flair and style. Man of Tai Chi starred Tiger Chen, a protege of Yuen Woo-ping and a member of his fight choreography team on The Matrix.

The John Wick sequels took their mantra of martial arts to even higher levels of creativity and flair, staging fistfight sequences that utilize everything from motorbikes to horses and dogs. Incidentally, Tiger Chen managed an uncredited cameo as a Triad assassin in John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum (2019).

There is a reason that The Matrix stands up so well over 20 years later. Obviously, the effects are a huge part of that, but even they will age eventually, overtaken by whatever new technology is developed over the next few years. What will not age, however, is Yuen Woo-ping’s boundless creativity, willingness to take risks, and insistence on perfection from his cast. Jackie Chan put it best in an interview when he explained that the reason why he is such a perfectionist is that film is forever. Any mistakes that end up on the screen are there for eternity.

Equally, the magnificence of martial arts is also etched into the higher echelons of cinema forevermore, and, for that, Yuen Woo-ping is a name that deserves to be known and spoken of with reverence, both inside and outside the film community.

This article was first published on November 17th, 2021, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂