It is now almost impossible not to think of The Matrix (1999) in tandem with the plethora of parodies that followed its release. The slow-motion dodging of bullets, so revolutionary at the time, was mocked mercilessly in Hollywood thereafter, from films as diverse as the Scary Movie (2000) franchise to Charlie’s Angels (2000).

But before Hollywood hailed the Wachowskis for revolutionizing the action genre, another director had been making what was dubbed ‘gun fu’ epics since the 1970s. John Woo is a name that has become synonymous with slick, stylized violence. Precisely what it is that makes Woo unique is evident both in his finished films and also through each individual action scene, which when compared and contrasted to his Hong Kong contemporaries shows a true auteur at work. Woo is in many ways as distinct a subgenre as any in Hong Kong cinema, complete with cliches and stereotypical elements such as heavily stylized slow-motion and symbolism.

But before delving into that, we need to understand what the action cinema landscape looked like before Woo came on the scene. Shaw Brothers were the top production company in Hong Kong, churning out kung fu flicks on a production line, that was so slick that films could be written, shot, and edited in a matter of months, sometimes even weeks. That is not to denigrate their work in the slightest, indeed many of their films are now classics of the genre. The 36th Chamber Of Shaolin (1978), One-Armed Boxer (1972), and One-Armed Swordsman (1967) are signifiers of kung fu cinema. Crucially, they are all period pieces focusing exclusively on combat either unarmed or including medieval weaponry.

It is oft-quoted that Woo originated what became known as the ‘heroic bloodshed’ subgenre. However, just as they pioneered martial arts cinema, Shaw Brothers also spearheaded the gun-fu craze with the release of Hua Shan’s The Brothers in 1979. Serving as a direct inspiration for Woo’s first entry into the genre A Better Tomorrow, which was released over five years later in 1986, the central conflict of the film focuses on the complexities of criminality as two brothers, one a cop, the other a top mobster, play out a tragic tete a tete as their fates inevitably intertwine. It makes for a fascinating companion piece, not just from a plot point of view, but the directorial differences. This is not to denigrate Shan’s work, as his film still stands up as a terrific slice of genre storytelling.

How John Woo Honed His Style

Woo’s directorial debut was actually a straight-up kung fu film, featuring none other than Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung in supporting roles, along with veteran villain James Tien. Hand of Death (1976), although not in the gun fu genre, still saw Woo direct fight scenes with flair and style, long shots, and creative use of the camera. It is worth watching not only for early examples of Chan and Hung but to see Woo’s eye for action in full force years before his most well-known films.

Though it was Yuen Woo-Ping who was responsible for the fight scenes in The Matrix, it was Woo’s aesthetic the Wachowskis were paying homage to, perhaps most notably in the scene in which Neo (Keanu Reeves) fights with Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne) the first time. Utilizing many of the hallmarks of Woo, including slow motion and long takes, the scene is an amalgam of Woo’s wizardry and the Wachowskis’ own action style.

It’s very easy to say Woo is a magnificent action director – that is a given at this point – but what is it exactly that has cemented Woo’s output as classic of the gun-fu genre? To try and quantify what makes an action scene ‘great’ is so subjective as to be impossible to pin down. His films are often called stylized, but what that means in practical terms is that Woo makes use of symbolism to tell the story, this being most often parodied through his liberal use of white doves.

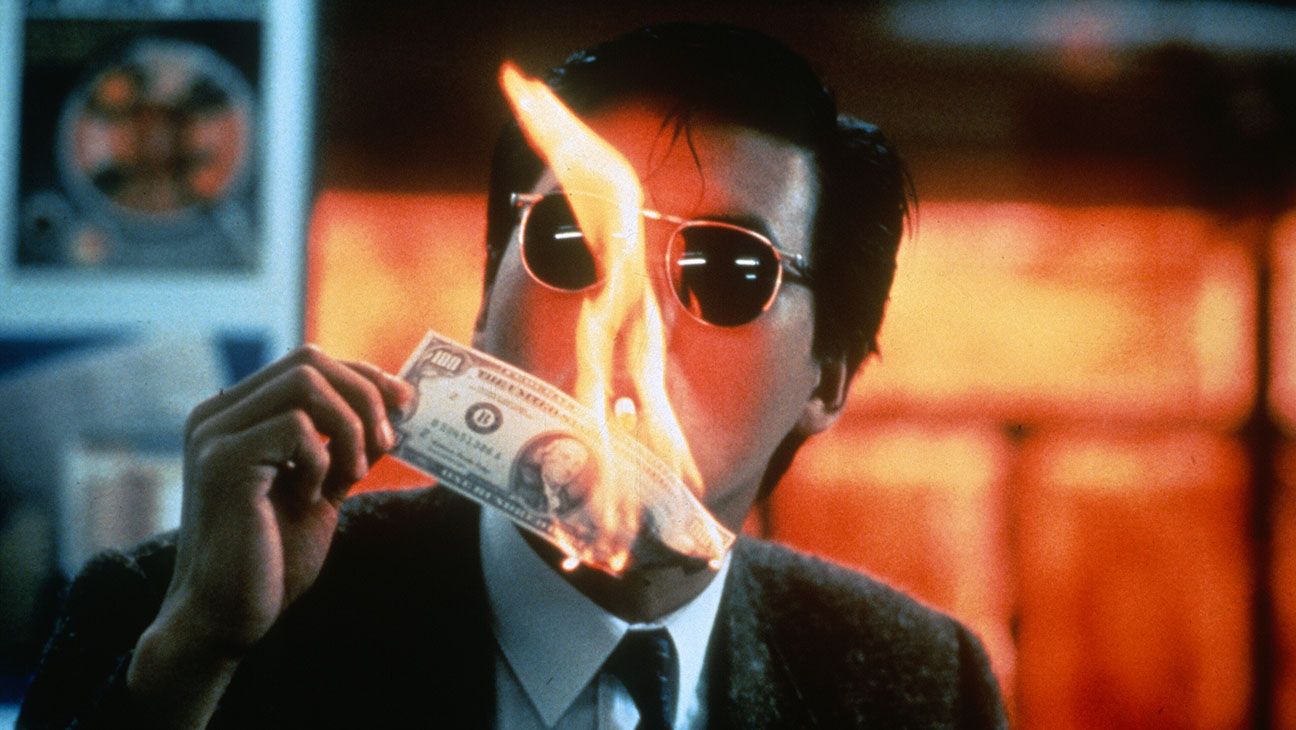

Perhaps the finest example of Woo’s terrific technique can be seen in the seminal shoot em up Hard Boiled (1992). What could have been a generic ‘cops and robbers’ actioner is brought spectacularly to life by Woo’s eye for action. Specifically, I want to examine a scene that occurs at the start of the film, because it contains many of the elements later used by the Wachowskis.

The scene is set in a teahouse. For context, Hard Boiled, living up to the genre of its namesake, encompasses a violent power struggle between Chow Yun Fat’s Inspector ‘Tequila’ Yuen and Alan (Tony Leung Chiu-wai), an undercover officer posing as an assassin. The film is now viewed as a classic of Hong Kong cinema, with many praising its action as some of the greatest ever committed to celluloid. The teahouse scene is a testament to that. The scene builds slowly, the camera weaving through the tables to give the audience an idea of the geography of the space, which is crucial for the events about to occur.

A mixture of tight close-ups and point-of-view shots from a distance put the viewing audience on edge – conflict, it seems, is inevitable. When the brutal battle finally kicks off, a good six minutes into the film, Woo ratchets up the pace and the intensity, and here is where we can really see why Woo is revered by the public and peers alike. Where a lot of American action films utilize hyperkinetic editing, quick cuts, and shaky camera work to convey chaos, Woo’s camera glides – it isn’t for nothing his action films are described as ballistic ballets.

In an article on the scene for Director’s Guild Quarterly, Woo recalled:

“I like to choreograph action pretty much like dancing. When you dance, you feel the beauty of the body’s movement—the slide, slow-motion, flips, or whatever.”

The Creative Legacy of John Woo

The Matrix turned slow motion into a cliché, and that’s important to think about when viewing Woo’s work, especially for the first time. Parody may have robbed these techniques of their power, but that is soon forgotten after witnessing Woo’s baroque brutality. The subway shoot-out and subsequent fistfight is perhaps the most obvious Woo homage, utilizing as it does many tricks taken from his arsenal.

As Neo and Smith prepare to fight, they leap towards each other as the camera swoops around them in slow motion, before crashing to the floor. This technique came to be known as ‘bullet time’, which was also used in the now-famous scene in which Neo dodges bullets by bending over backward. Compare this to the shootouts in Woo films. The main difference is that Woo uses slow motion to enhance the impact of both the gunplay and the reactions as people are hit. If they were played at normal speed, the scenes wouldn’t have nearly as much impact. The majesty comes from each gunshot being treated like its own story, each death a momentous event. In Hollywood pictures, goons are gunned down indiscriminately, whereas, in Woo’s pictures, each death means something, which arguably makes them more realistic – these are human beings being killed, and Woo makes the loss of life felt rather than simply treating the scene as fodder.

The hospital shootout is another seminal scene, which has inspired countless imitations. The hospital plays host to a bloody battle, as Yuen and Alan fight their way through a gang of triads. What makes this scene work is ironically its simplicity. Woo trains his camera on his actors and simply follows them, never cutting away as the carnage unfolds. In many respects, this makes it one of the least overtly stylized scenes in Woo’s career, with no doves or even slow motion. It is more akin to a documentary, as bodies are blown apart and crash through windows and doors.

In the context of The Matrix, though, the scene that would have been a one-shot actually had to be ditched. It was to be Carrie Anne Moss’ lobby escape at the start of the film. However, during rehearsals, Moss sustained an injury to her leg and was unable to complete the stunt in one take,

So how does Woo achieve the astonishing results we see onscreen? Like any great director, Woo knows his cameras inside out. During an interview with Premiere magazine to coincide with the release of Mission Impossible 2 (2000), Woo explained:

“When I’m working on a scene, I have the whole thing in my mind: the action, the tempo. When I’m shooting I know exactly what I need for every shot, every setup, and also about the speed of the camera – which angles use double speed, which ones use slow motion. I also listen to music – the music tells me the time.”

In this respect, the production process for The Matrix was similar. The Wachowskis storyboarded the action sequences through what is the 21st-century equivalent – pre-visualization. This entailed creating each action sequence with CGI and shooting the fight choreography using stuntmen. This not only meant that actual filming could be completed more quickly, but that any errors could be corrected before committing them to film. It also allowed for experimentation and for each action sequence to be choreographed to the highest quality before filming commenced. This is now commonplace in Hollywood, with Alpha Stunts, the stunt company run by Reeves’ stunt double Chad Stahelski, famous for being meticulous in the amount of work they put into planning their fight scenes for the John Wick films which Stahelski directed.

John Woo’s impact on action cinema cannot be overstated. After the wider world took notice of his style, Hollywood had to up their game, and it took until the release of The Matrix for a Western action film to have as much influence. Cinematic gunplay has never been the same since the release of A Better Tomorrow, with every subsequent scene striving for the standards that Woo set. Woo has been steadily making action films in the 21st century, with perhaps the most exciting upcoming project being Silent Night, his return to Hollywood after almost 20 years in an action film that will contain no dialogue.

If you love The Matrix but have yet to experience the majesty of one of Woo’s works, then find yourself a copy of Hard Boiled and prepare to get drawn into the hyperviolent world of Woo.

This article was first published on December 14th, 2021, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂