Science fiction in the 1970s was like everything else: groovy.

Gone were (for the most part) the hard-hitting social satires of the 1960s: instead jumpsuits, monster-of-the-week, and pop culture influences abounded. This was also true in musical terms, as prog and folk rock began to fall by the wayside in both the United Kingdom and America in favor of the more image-focused glam rock and disco. Pop albums with covers featuring robots and girls in silver dresses began to appear. The musical genres also began to make themselves felt in TV and film as diverse as Starsky and Hutch (1975-1979) and Space: 1999 (1975-1977), both through their theme tunes and their content. It seemed inevitable that the two most integral types of pop culture at the time should join together.

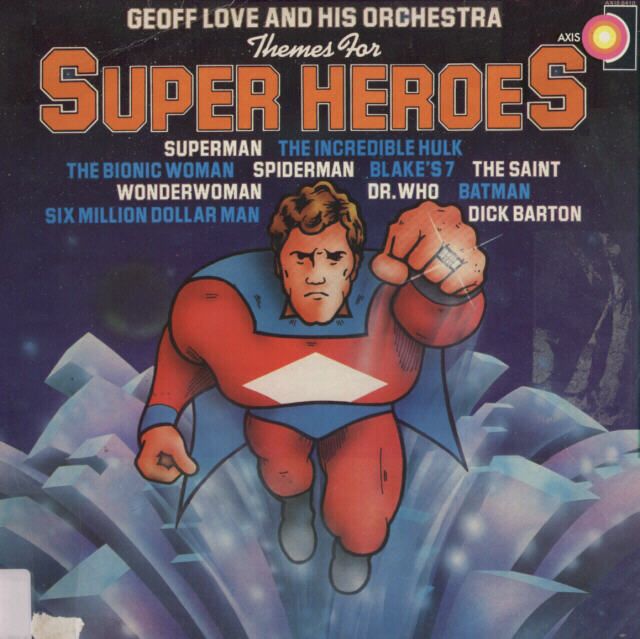

1970s science-fiction, particularly the live-action series of Gerry Anderson (Space: 1999, of course, but also UFO), Blake’s 7 (1978-1981), Star Wars (1977), the 1979 Star Trek film, and other properties such as The Six Million Dollar Man (1973-1978), has been given the name ‘disco sci-fi’ by many outlets such as PopMatters and Disco Mania. But the influences of disco music and fashion cannot only be felt within their series: many theme tunes and instrumental scores took influence from disco.

Just look at the theme to Space: 1999 Season 2, with its pounding, over-dramatic disco beat and electronic score. Others received disco or pop treatment at the same time, creating a feedback loop between the two. Some pop videos also took visual cues from sci-fi, from costumes to blue screen and early video effects, which were then replicated on television pop shows such as Top of the Pops. In short, the 1970s was the decade where science-fiction went pop; when sci-fi went disco.

The Sci-Fi Influence on Disco

This was not, however, a completely isolated phenomenon: retroactively termed ‘Space Age Pop’, many artists of the late 50s and early 60s replicated the electronically driven sounds of films such as Forbidden Planet (1956) within their work. From Sid Bass’ From Another World (1956) to Joe Meek’s Telstar (1962), the musical conventions and iconography of space and science fiction were already leaking into the musical mainstream. Prog rock also set the template for later space disco, as they incorporated synthesizers into songs that sought to break away from a restricted idea of space, inner and outer, whilst of course, glam rock artists such as Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars took influence from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1962) into their art. Disco also became a reaction against more down-to-earth, self-consciously “real” movements like prog or Northern Soul.

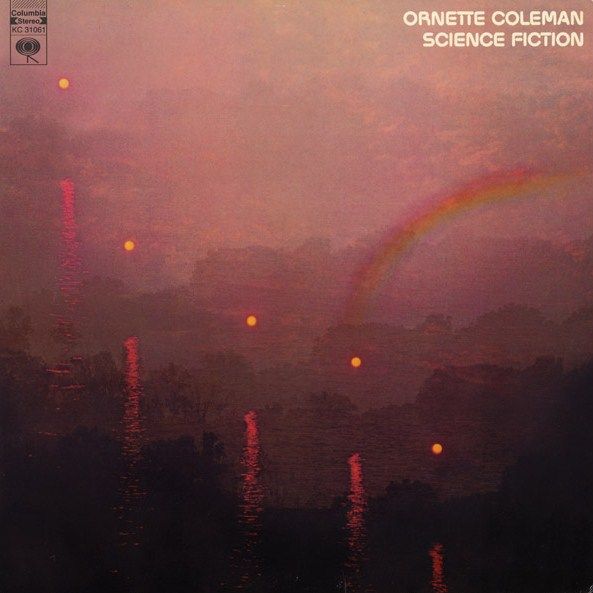

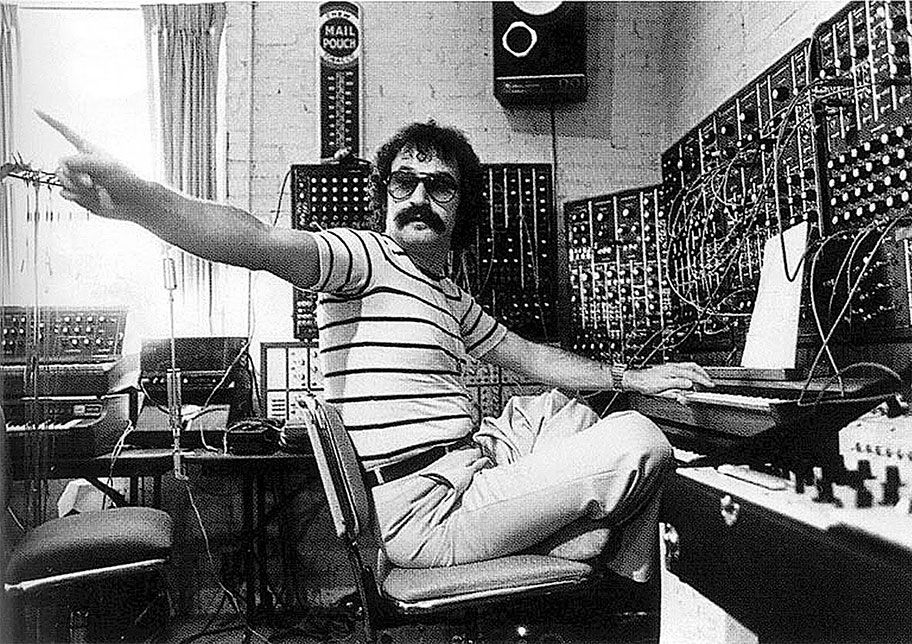

Afrofuturism began to experiment with mixing space-age sounds with African-American art, in tracks such as Ornette Coleman’s Science Fiction (1972) and LaBelle’s ‘Lady Marmalade’ B-side Space Children’ (1974). As disco began to emerge from the underground clubs of the early ‘70s, it brought with it notions of electronica, especially in the work of Giorgio Moroder, whose use of the Moog set the template for the synth-heavy style of the ‘80s.

In this fertile atmosphere, with its focus on space themes and out-of-this-world instruments, the popularity of science fiction film was also brewing, as the primary era of ‘Space Disco’ largely follows the trajectory of the Star Wars original trilogy. As Tim Worthington, author of Top of the Box: The Complete Guide to BBC Records and Tapes Singles, explains:

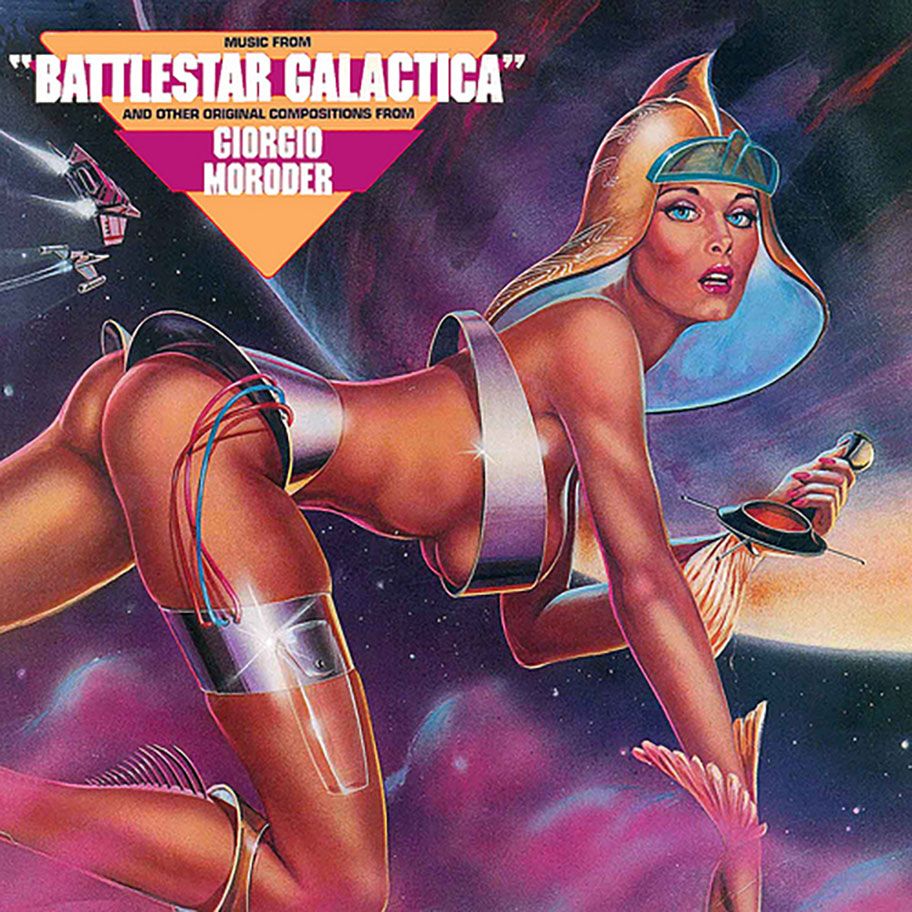

“Sci-fi in the late ’70s on the other hand had got a bit, well, disco though, with tacky spaceship designs, glittery spacesuits, and so on – things like Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, Battlestar Galactica, Space Sentinels, even Star Wars to an extent, and of course, Rose denounced K-9 as ‘a bit disco’ in the revived Doctor Who. Plus they all had disco-funk-styled soundtracks too, as presumably, that was what was cheapest and easiest to get session musicians to do at that point as well as being modish and fashionable.

“Then there were disco outfits doing in that same direction as well – Labelle, Space (the French band), Hot Gossip etc – and they sort of met in the middle. When you look at some of the Top of the Pops performances of things like [Dee D. Jackson’s single] ‘Automatic Lover’, they could be straight out of a nightclub scene in Battlestar Galactica.”

These blockbuster successes, alongside those of the other films listed above, propelled the alien into the mainstream, as did disco, with its parade of the “other” in the form of queer, inclusive communities. Thus, the stage was set for disco renderings of science-fiction theme tunes.

Sci-Fi Scores Get a Disco Makeover

Star Wars had also changed sci-fi through its preponderance of merchandise: as Worthington says “it was mass-marketed but only on terms that the studio was happy with, so everything looked and felt ‘official’ as part of the universe (or at least what we thought was the universe until we were told otherwise).” The incoming John Nathan-Turner era of Doctor Who also had an impact, due to its freewheeling licensing. In short, musical innovation, late 70s style, a new wave of popular science fiction, and innovations in marketing combined to create the perfect storm for disco remixes.

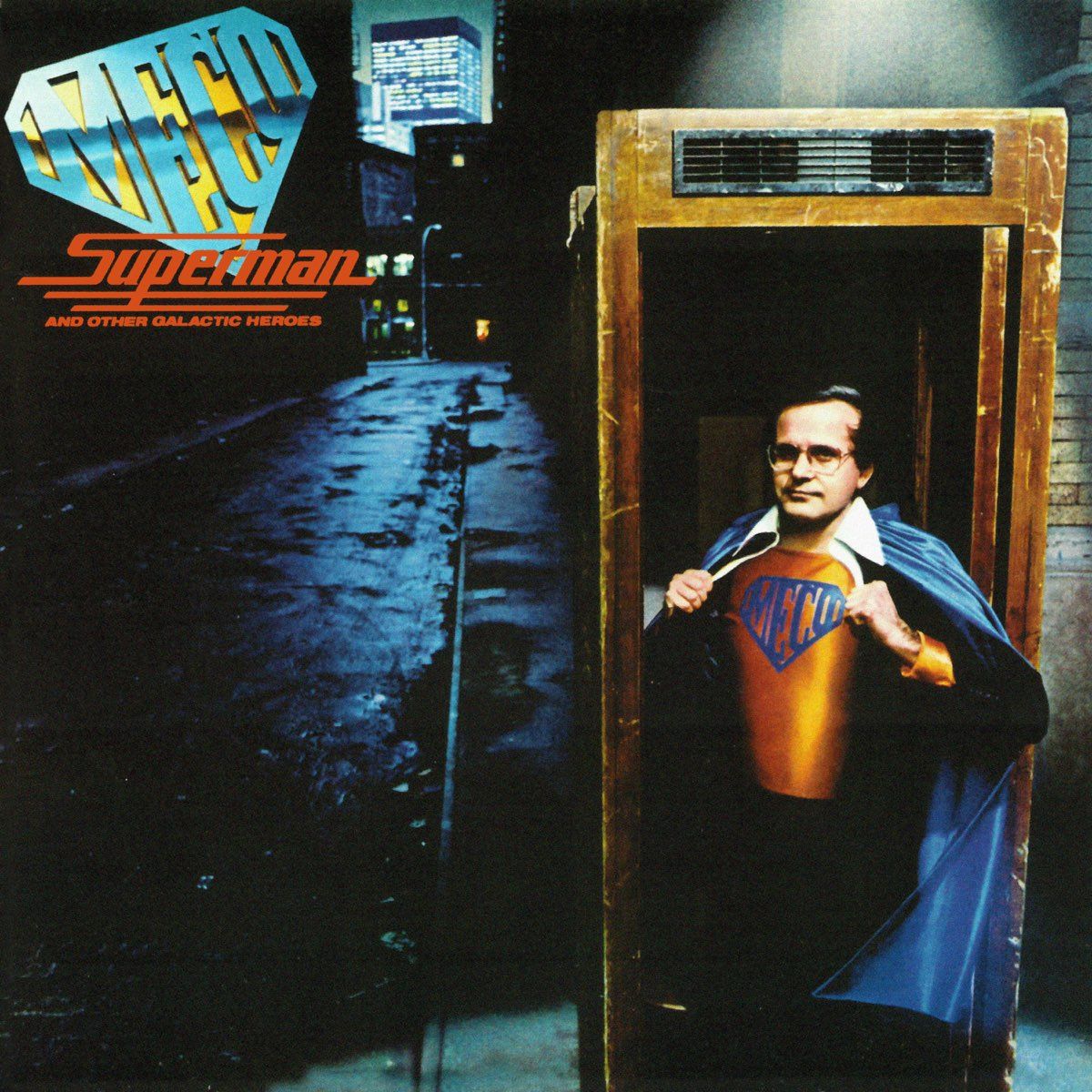

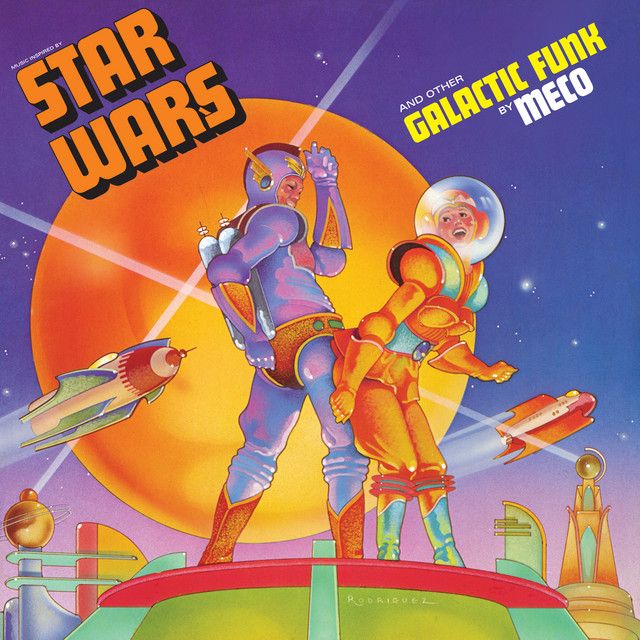

The most famous of these is undoubtedly Meco’s ‘Star Wars Theme/Cantina Band’, taken from the album Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk, and which reached Number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in October 1977. Incorporating the film’s main theme, cantina band, and Princess Leia’s Theme, alongside sound effects including the hum of a lightsaber and R2-D2’s ‘voice’, this track set the template for successful disco renderings of themes that retained their musicality and incorporated a danceable beat.

Meco – known to his mother as jazz musician and record producer Domenico Monardo – told Starlog No. 11 (January 1978): “I saw the film three more times. By the second showing, I began hearing the music. John Williams does some amazing things in the movie but everything is hidden by the action. All those beautiful themes.

“The fourth time I saw Star Wars I just listened. I bought the soundtrack and thought, ‘Hey, they could be doing more’.”

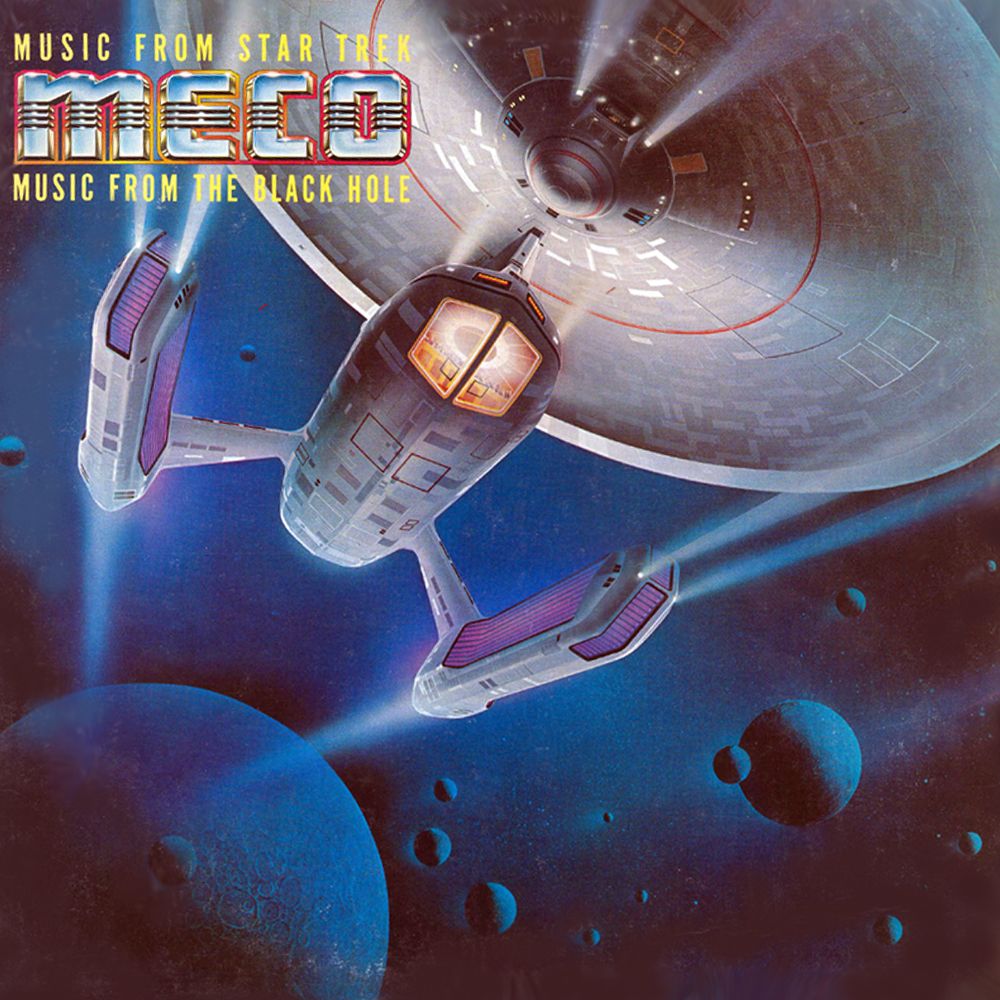

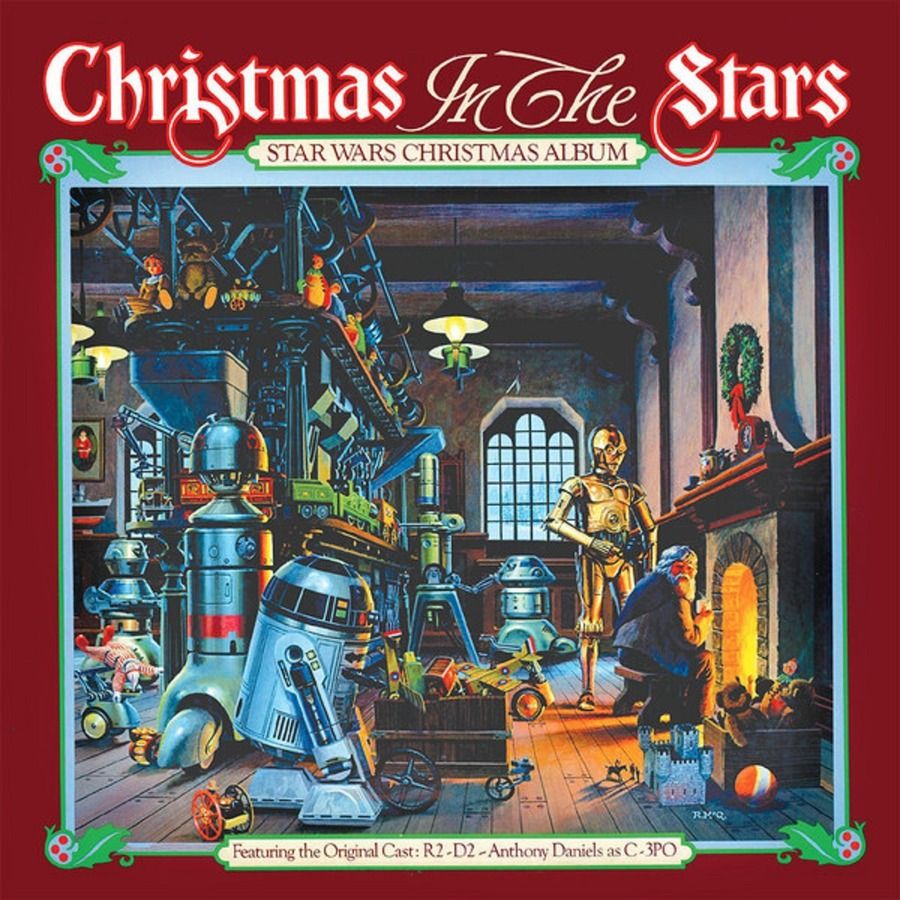

Meco followed this success with Superman and Other Galactic Heroes (1979), featuring versions of the John Williams Superman and Neal Hefti Batman themes, and Music from Star Trek and the Black Hole (1980), which included versions of Jerry Goldsmith’s The Motion Picture theme and that of John Barry’s The Black Hole. Meco also made a startling move into the Christmas album market with Christmas in the Stars: Star Wars Christmas Album (1980), a project as seasonally deranged as the Holiday Special, and featuring songs from C-3P0’s Anthony Daniels about droids making toys for Santa Claus.

Yes, really. Here, Meco set the template for the weird and wonderful relationship between disco and sci-fi, but it could have been so much weirder. He told Starlog No. 43 (February 1981):

“The last song, ‘The Meaning of Christmas’ – the tearjerker – was supposed to be Yoda’s song called ‘Help You I Can’. It was semi-pseudo religious, much more moving even than this is and right now it’s pretty moving.”

Other forays into Star Wars disco included The Droids’ (Do You Have) The Force (1977), a series of instrumentals from French producer Yves Hayat inspired by (but not including) extracts from John Williams’ score; Sarah Brightman and Hot Gossip’s I Lost My Heart to a Starship Trooper (1978), which contained both musical references to and direct quotes (Darth Vader, Flash Gordon, ‘Close Encounters’, etc) from popular sci-fi properties; and M.B.4’s Ewok Celebration and Star Wars (1983), which includes a snippet of the Ewok song of triumph, ‘Yub Nub’.

Sadly, we have no idea what M.B.4 – Italian disco legend Mario Boncaldo – was thinking but the end result is a banger.

Sci-Fi Disco Hits its Peak

Giorgio Moroder recorded an extended remix of the Battlestar Galactica (1978-1979) theme for a 1978 release, and the Alien (1979) theme was disco’d by Kenny Dayton, who recorded under the name Nostromo. Other bands took inspiration from science-fiction properties but created their own narratives around their music, such as the Viennese band Ganymed, who were supposedly aliens from Ganymede and showed it by dressing as aliens complete with masks and a lead singer dressed somewhat like a Doctor Who companion. Tracks included ‘Hyperspace’, the story of an astronaut killed by a space siren, and ‘S’Punk’ about a discontented youth turned energy vampire ready to “let my tentacles come and get you!”

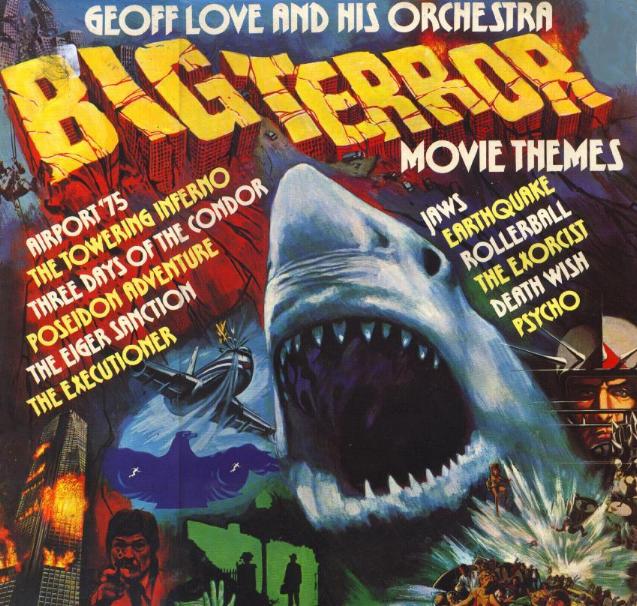

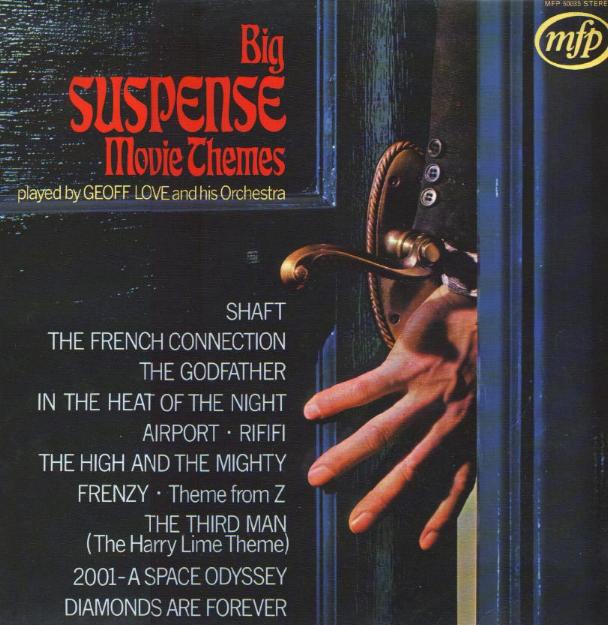

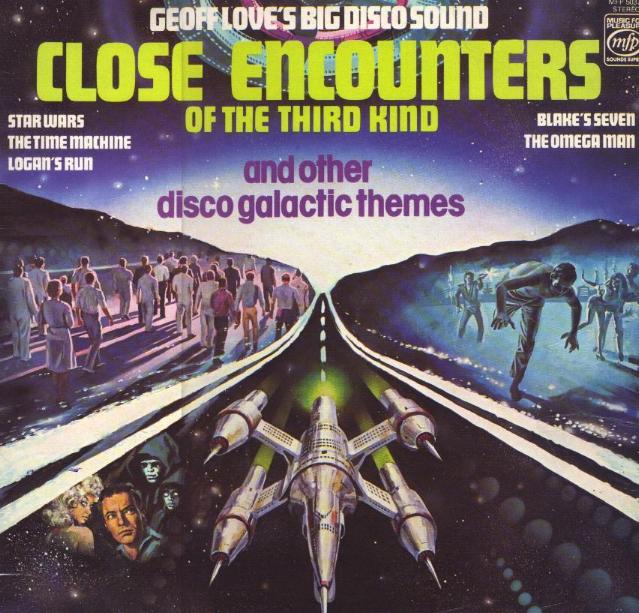

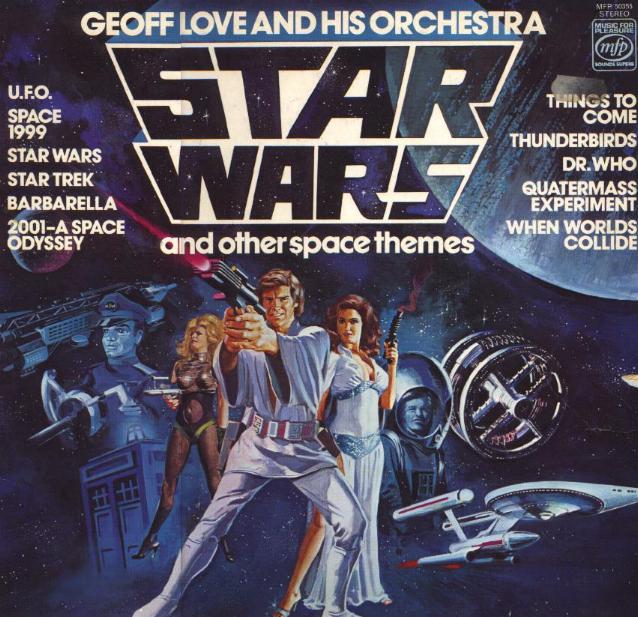

The UK in particular was adept at producing sci-fi covers, most notably from renowned easy-listening giant Geoff Love. Produced for his regular label MFP (Music for Pleasure), Love released Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Other Disco Galactic Themes (1978), which included reworkings of American imports like Star Wars, Logan’s Run (1976), The Time Machine (1960), and The Omega Man (1971), alongside a version of homegrown hit Blake’s 7.

The sheer range of themes here suggests their potency as memorabilia of their initial film, especially at a time when few were available outside of occasional television appearances. Versions of Jaws (1975), Tales of the Unexpected (1979-1988), and even Colditz (1972-1974) – the series covering the Second World War prison camp – appeared. Similarly, the inclusion of both American and British properties shows how they were foregrounded as the greatest generators of sci-fi content at the time, on both film and television, a fact often ignored in the emphasis on film sci-fi across much criticism. These albums also managed to replicate the sound of “big disco” with what Worthington describes as “a band of cash-in-hand studio players who would have wondered why there was nobody playing cribbage at discos through a couple of tunes they’d probably only heard for the first time the day before for a budget-priced album being recorded against the clock.”

These albums and releases were profitable largely due to the popularity of what they were covering with kids. To quote Tim Worthington:

“What would be more likely to keep a youngster who won’t stop going on about Star Wars despite the fact that they haven’t actually seen it quiet for an hour than an album with some of the music on it?”

Disco Sci-Fi’s Back, Baby

In a way, the albums replicate the cashing-in on the sci-fi craze as Moonraker (1979) or the same way that the ’60s tie-in ‘Star Trek Helmet’ had slapped the word ‘Spock’ on the front and expected it to work. Later, lounge music and nostalgia began to play a part in popular culture. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the 90s saw reboots of 60s action-adventure series The Avengers, a Gerry Anderson craze, and a lounge-lizard cover of Oasis’ ‘Wonderwall’ a la Quincy Jones; more people began to turn back to both the original recordings of these themes and their disco remixes.

The impact of both disco and science fiction can be clearly seen on the unreleased Pulp demo ‘We Can Dance Again’, a perfectly good disco track that may have been a genuine hit. Why wasn’t it released? It sounds eerily similar to Geoff Love’s cover of the theme from Blake’s 7. The impact of the disco remix as emblematic of its era has continued even into the modern day. James Gunn produced the ‘Guardians’ Inferno’ music video as part of the promotional campaign for Guardians of the Galaxy: Volume 2 (2017). A bedazzled, bacofoil tribute to tie-in singles of the past (complete with requisite David Hasselhoff) the video gives the Guardians theme tune a pounding disco beat, not completely unlike Meco. Not only does this speak to Gunn’s tendency to repurpose old music trends for his projects (as we’ve most recently seen in Peacemaker), but also demonstrates how the kind of found-family, disco science-fiction of Guardians is inextricably linked with the era it originated in: the 1970s.

So why have disco remixes retained their power? “When they work, it says a lot about what a tremendous piece of music the original composition is,” says Tim Worthington. This can also be seen in the endless reworkings and remixes for reboot films, say with Star Trek (2009)’s use of Alexander Courage’s original theme, or the slight adaptations to the Star Wars overture as seen throughout the Prequel and Sequel Trilogies. Adapting these iconic pieces of music into new mediums allows people to enjoy them in new ways, and to appreciate their original qualities. And the potency of these remixes, coming up to 50 years after their original release, also testifies to the remaining power of disco. Artists like The Weeknd and Dua Lipa have heavily leaned into the disco genre in recent years, which in turn has led to a resurgence in original recordings, even ones as obscure as those listed above.

The science fiction disco remix track might seem like something out of the ark, but it provides a snapshot of a time when two of the world’s greatest film and music genres collided. They suggest the beginnings of a merchandise obsession that is yet to dissipate, the inventiveness of music producers across America and the United Kingdom, and are often much better than you’d think they would be. Their influence has remained for music nerds, sci-fi fans, and cultural historians alike. Whilst they might have been produced by session musicians or young producers inspired by blockbusters, they retain their groove regardless.

This article was first published on March 3rd, 2022, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂