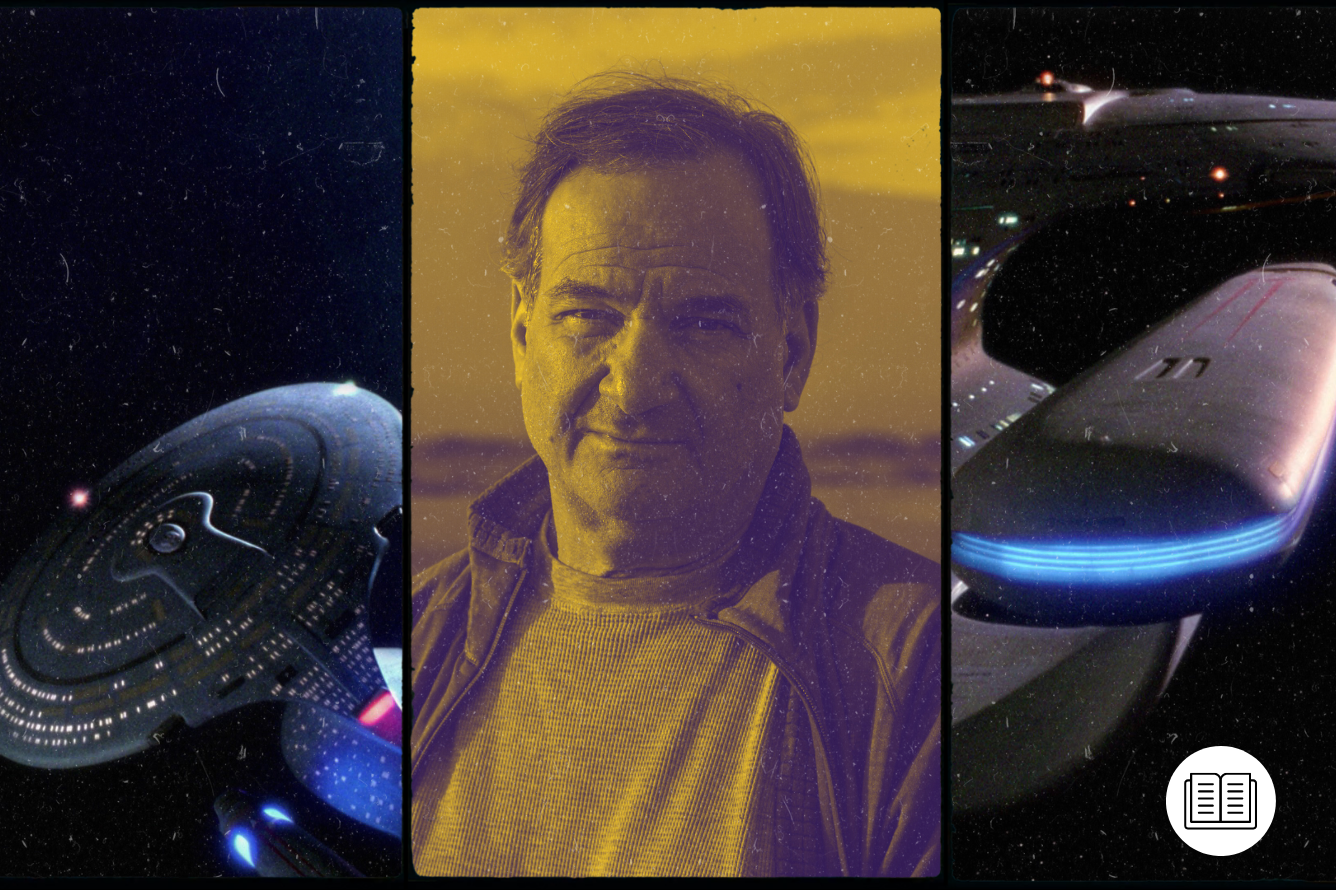

Few people have shaped the VFX industry as much as Rob Legato has. On top of his three Visual Effects Oscars – for Titanic, Hugo, and The Jungle Book – he also provided the effects for Apollo 13, Armageddon, and the first Harry Potter film. But before all of that, he was the guy who brought the USS Enterprise (NCC-1701-D) to life. His background in studying cinematography and shooting commercials gave him the hands-on, all-rounder approach needed to cope with the demands and pressures of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

Starting Out on The Next Generation

When ILM did the VFX for ‘Encounter at Farpoint’ (S1, Ep1), the pilot episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, the plan was to shoot enough footage of the model Enterprise to provide stock footage for the entire season. But when the next episode rolled around, the script called for 15 new VFX shots in that episode alone. It was simply too time-consuming, and too expensive, to get a company like ILM to handle the VFX and model photography week in, week out – so The Next Generation’s VFX Supervisor had to get creative.

“Instead of it being this kind of mystique that only [companies like] ILM… could do these big Star Trek model shots, I figured I could do it. What’s the big deal?” Legato shrugs, demonstrating the willing-to-try-anything attitude that has now won him those Oscars, as well as two Emmys for his work on TNG and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.

Legato developed his fearlessly creative approach to VFX during his time in commercials in the 1980s, where, despite being a film school graduate with no background – or particular interest – in VFX, his willingness to experiment with filmmaking techniques made him the company’s go-to effects guy. His philosophy at the time was: “Try it. It’ll only fail, and then you might learn something from failing.”

It was a philosophy that stood him in good stead when he joined The Next Generation – and a philosophy that was slightly at odds with ILM’s more rigidly organized way of doing things.

Luckily, the TNG producers were happy to let him put his own plans in place, so long as the show came in on time and on budget. Legato recalls that the attitude from producers at the time was “shoot as fast as you can, we’ll take just about anything,” but for Legato the look was just as important as the speed. TNG launched at the height of the VHS boom, so Legato realized that “in the same TV set that you watch Star Trek: The Next Generation, you could put a cassette tape in and watch Close Encounters [1977], and you can watch the Star Trek feature [films]. You’re used to seeing them in the same venue.”

He wanted to make sure that, while the effects might not quite match those of a high-budget feature film, they would at least be impressive by TV standards.

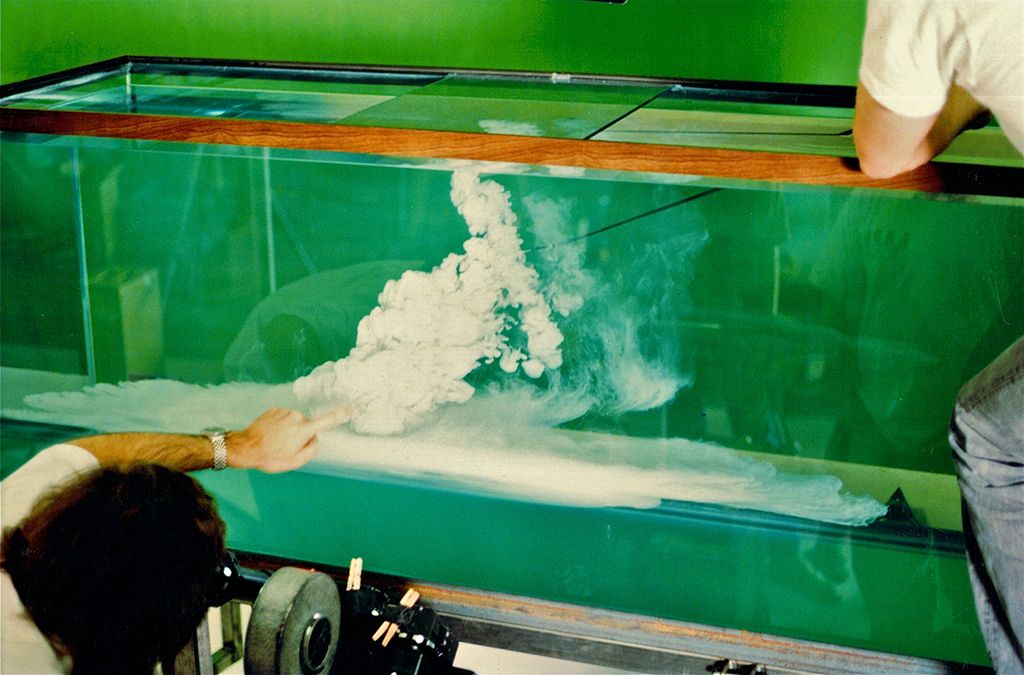

In the early days, Legato “would shoot things in my basement to give it a lot more production value. I knew how to light, so if you shoot in smoke and have a light beam and shadows and shafts, it looks like you have a lot more things than you really have. So you could make something out of nothing. Because there wasn’t really a rule book, and no one knew what I could do or was doing, I was able to do whatever I wanted.”

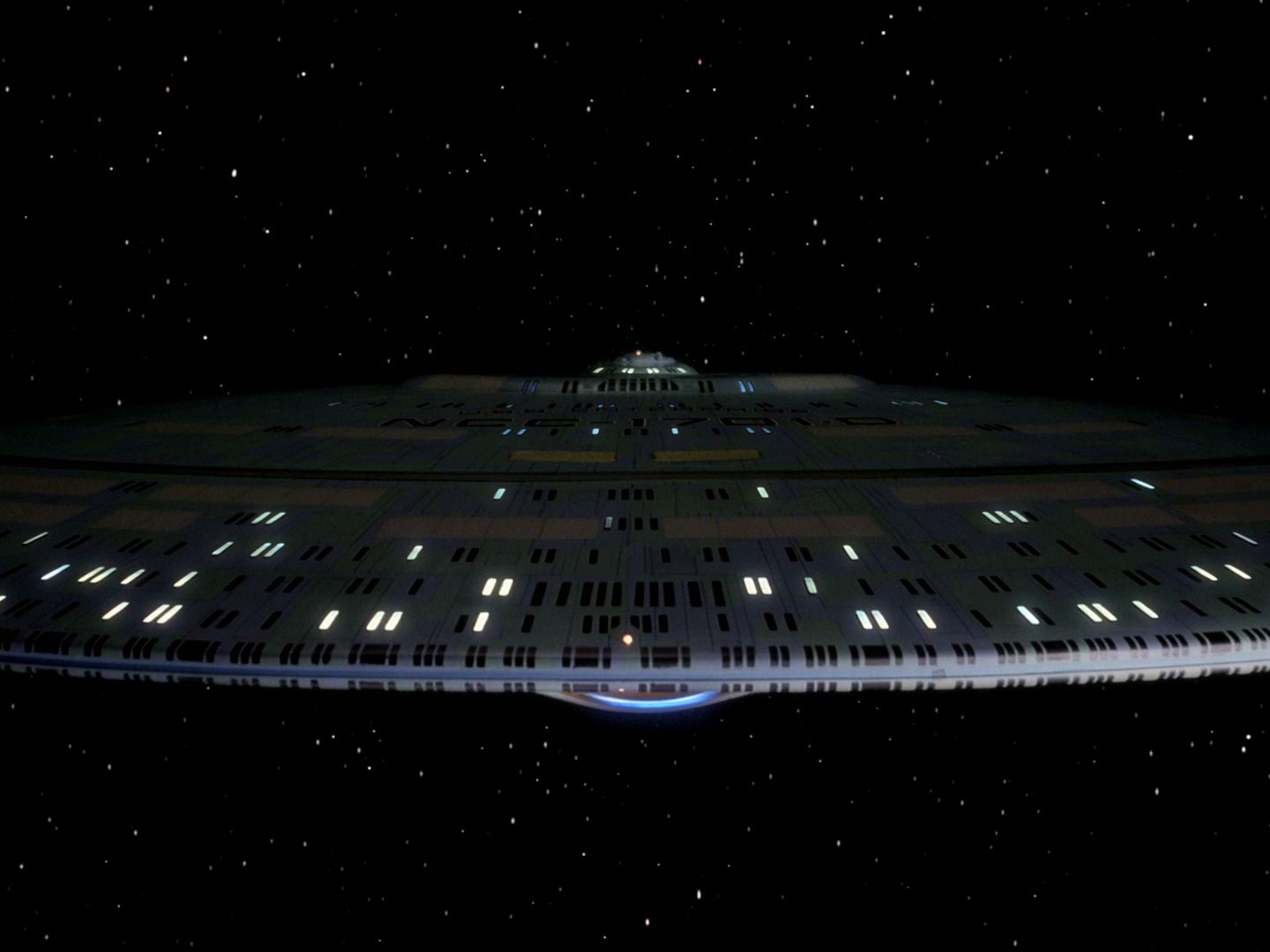

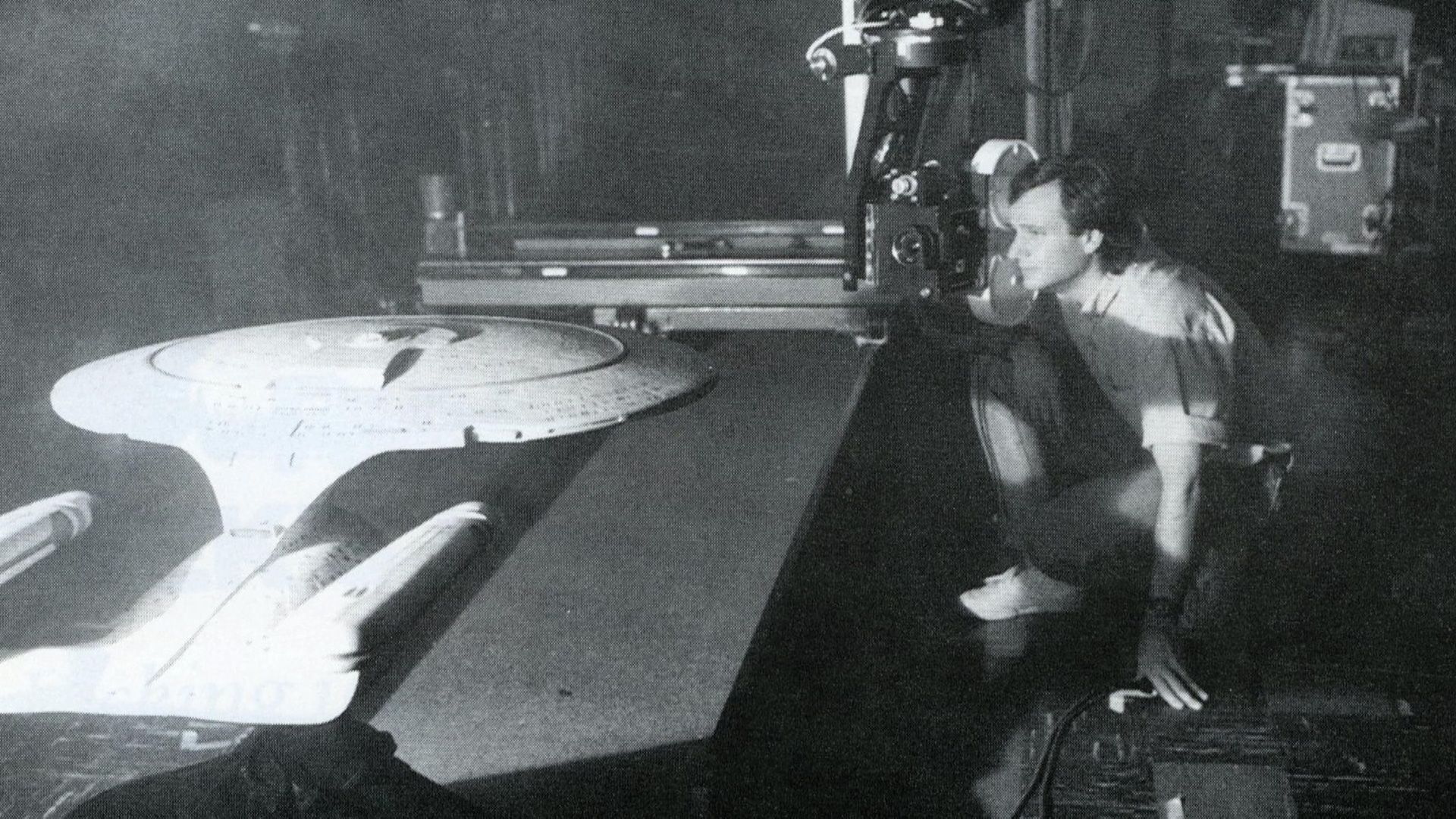

The process of shooting the ship and planet models was one of gradual discovery, and Legato and the crew essentially learned and developed the process from scratch. They used motion control, the process by which a fixed camera move could be programmed into a computer, allowing the camera to replicate the exact move multiple times. That move could be used to separately shoot the ship, the stars, and any other element needed in the shot, and they could all be composited together into one shot in post-production.

“The beginning was very tame, we did lock-offs,” Legato says. “The ship would move but the stars wouldn’t move because we needed to motion control those, or create them in some way.”

You might think that a franchise as scientifically forward-thinking as Star Trek would have come up with some sort of advanced technique for creating the spacescapes that the Enterprise flies through – but no. Legato and his team “put a bunch of pinholes in a black piece of paper [and] backlit it.”

It’s just one example of the quick, off-the-cuff thinking that was needed to bring TNG in on time and within budget. Legato recalls that they had a week per episode for TNG, and that in the early days he would regularly work 18-hour days, simultaneously handling post-production effects on one episode, shooting the next episode, and prepping for the one after that. Speed and creativity were of the essence.

In the end, once their process was locked in, Legato could shoot “maybe eight shots in a day. ILM would do one shot in a week… I could do a tremendous amount of decent-quality work. I wouldn’t say it was great quality work, but decent quality work that was different for TV.”

On Deep Space Nine, they brought in a guy who had previously only done features VFX work, who “said that I shot more in two weeks than they would shoot in a year on a feature.” Legato would refuse to storyboard because he enjoyed the process of discovery and the “happy accidents” that could happen while shooting and lighting models. As well as making the process more creative and flexible, it also made it faster, without having to go through the rigmarole of getting shots approved first.

“I just got better week after week, because I was trying new things without having to go through a process,” he says.

Shooting Models More Dynamically

Soon, they began to iron out their process and make changes. The Enterprise model that ILM built was six feet across, which limited the ways they could shoot it. Their studio space wasn’t huge, and they could only get the cameras so far away from the model.

“I said that for me to do a better job I need a small, half-size Enterprise that has more detail on it because I used to like to light it to look more like a feature. The original Enterprise, as designed, was supposed to be this sleek, plasticky-looking thing, well of course it makes it look like a model when it’s just a sheet of plastic with nothing to catch the light.”

For $35,000, Tony Meininger (who later did the models for Titanic) built a three-foot Enterprise.