Say “Threshold” to any Star Trek fan, and you’re bound to get a reaction—a laugh, an eye roll, a scream, an exasperated sigh so loud you could hear it from the outer edges of the Alpha Quadrant.

Fans celebrate its anniversary on social media—#ThresholdDay is on January 29—and have had tattoos honoring it. When I asked people I know their opinions, I heard the whole gamut, from “oh, it’s fun” to “it’s annoying”, “it’s the worst kind of Star Trek,” and “You can never truly recover after seeing it,” and “I remember yelling.”

For the uninitiated, ‘Threshold’ (S2, Ep15) is the name of a Star Trek: Voyager episode that’s bonkers, divisive, and appears on almost every ‘the worst episodes of Star Trek’ list I’ve read.

Transwarp Speed and Infinite Velocity

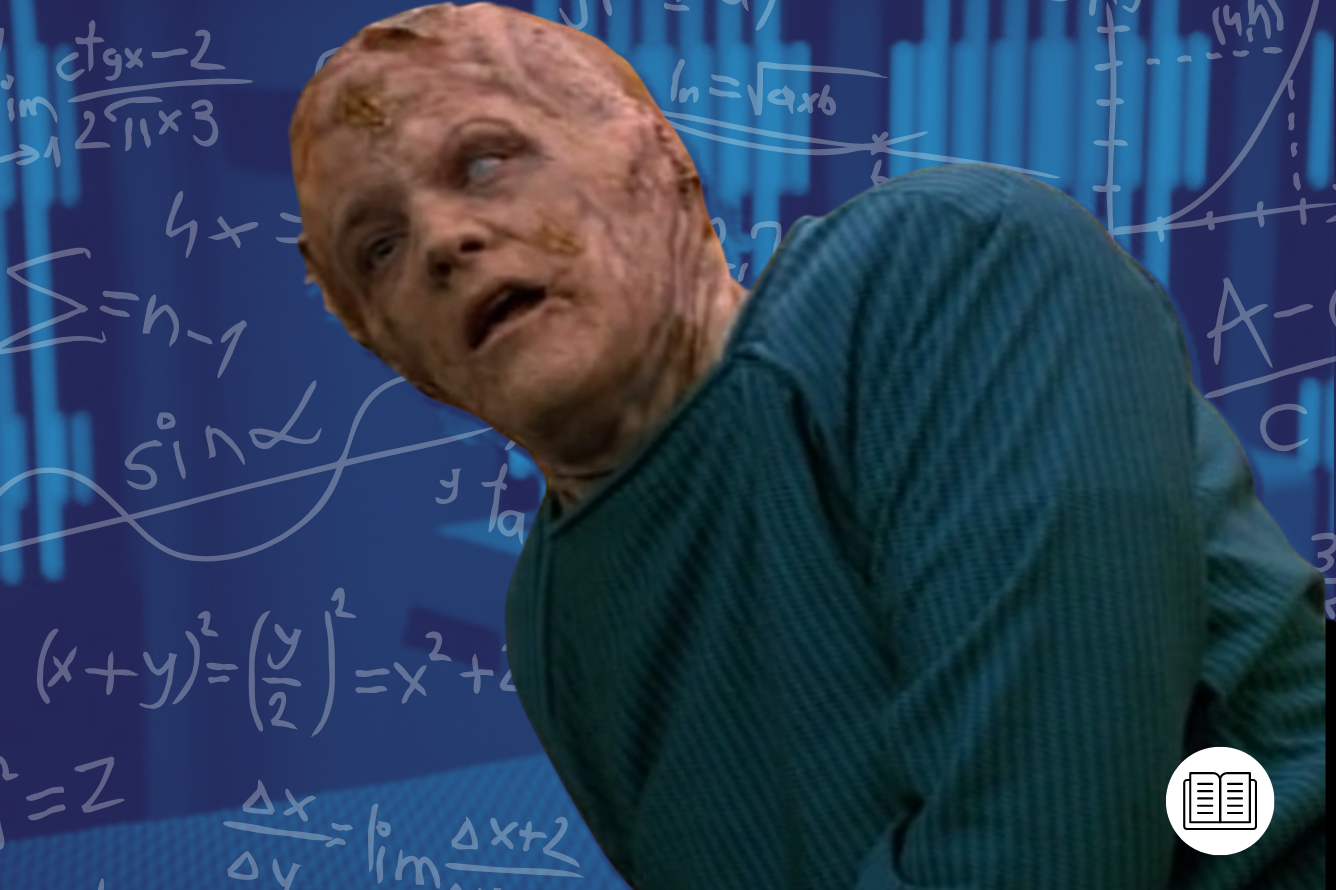

In ‘Threshold’, Lieutenant Tom Paris (Robert Duncan McNeill) takes an experimental shuttle for a spin. He hits Warp 10, a speed so mind-bogglingly fast that it breaks the ‘transwarp barrier.’

Transwarp is discussed several times throughout Star Trek’s history, but the meaning changes a bit each time. If we dissect the word, it simply means the other side of warp—but what’s there?

Going by the explanation in ‘Threshold’, Ensign Harry Kim (Garrett Wang) says that achieving transwarp speeds would mean you’ve reached “infinite velocity”.

Paris further explains—or confuses—things by saying: “It means that you would occupy every point in the universe simultaneously. In theory, you could go any place in the wink of an eye. Time and distance would have no meaning.”

As you might expect, smashing the laws of Star Trek physics to pieces with your shiny ship has some unexpected consequences.

Upon returning to Voyager, Paris begins to change—he can’t drink water or process oxygen, dies briefly, comes back to life, has two hearts, loses his hair, his skin is peeling, vomits out his tongue, and becomes really aggressive.

Paris breaks free, attacks Janeway, and takes her with him back onto the shuttle before whizzing off again at Warp 10.

A little while later, the crew finds the shuttle abandoned on a planet with no sign of Paris or Janeway. All they see are two huge space newts. Yep, you guessed it. That’s what they’ve turned into. And, if that wasn’t daft and deranged enough, they’re surrounded by what appears to be their offspring. (The Vagina Museum in London once published a fantastic Twitter thread about the details of space newt mating.)

On 29th January 1996, "Threshold", the Star Trek: Voyager episode where Captain Janeway and Tom Paris turned into giant space newts and had babies first aired. In advance of #ThresholdDay we aim to answer a burning question: did Paris and Janeway fuck? If so, how did they fuck? pic.twitter.com/Hp3sA4Ix2W

— Vagina Museum (@vagina_museum) January 28, 2022

I know what you’re thinking. Was it a mutating disease laying dormant in the shuttle’s environmental systems activated by transwarp travel? Or maybe aliens lurk in the bits between space and time, waiting to replace the two Voyager crew members?

Nope, it’s revealed that all of the transwarp adventurings accelerated the natural course of evolution—those giant amphibious creatures Paris and Janeway become are all of us in the future.

“The mutations we observed are natural,” The Doctor (Robert Picardo) explains. “The changes within his DNA are consistent with the evolutionary development of the human genotype observed over the past four million years.”

I’m confident I could write a whole book unpicking this one episode’s many confusing and nonsensical threads and still wouldn’t get anywhere. Asking questions like, why did they evolve into space newts? Isn’t the delicate balance of life on the planet that big space newt Janeway and big space newt Paris were found on fundamentally destroyed? And, crucially, what about their damn kids?

Before my blood pressure hits Warp 10, let’s bring things back down to a more manageable Warp 3 and find out the answer to the question at the core of ‘Threshold’. Is it really possible to speed up our evolution?

The Speed of Evolution

I spoke to Mohamed A. F. Noor, the Professor of Biology and Dean of Natural Sciences at Duke Trinity College of Arts and Sciences, author of Live Long and Evolve: What Star Trek Can Teach Us about Evolution, Genetics, and Life on Other Worlds, and a consultant on Star Trek: Discovery Seasons 3 and 4, who told me that first, we need to clear up a few things about evolution. “Evolution does not occur in an individual,” he explains. “So I didn’t ‘evolve’ from a baby into an adult – that’s just development.”

So what we see in ‘Threshold’ isn’t really evolution. But, fascinatingly, evolution, which is the spread of new inherited forms throughout a population, can happen pretty quickly—well, pretty quickly by real-world standards.

“Many people are aware of the classic example of the peppered moth in England,” Noor tells us. “In the early 1800s, all the moths were white-peppered colors, but following the blackening of trees and lichens on which they hid, fully black forms became much more common by 1900.

“The opposite then happened after the passage of the clean air acts in the 1950s and 1960s—now, the white-peppered form is by far the most common,” he explains.

Granted, the moths didn’t evolve to become a different color as quickly as Paris evolved to become a different species, but the changes happened within human lifetimes. By Trek terms, that’s slower than one-quarter impulse. In real-world terms, it’s remarkably fast.

When evolution happens rapidly, it’s often due to an external factor—in this case, the color of the trees. I spoke to Dr. Charles Foster, a Bioinformatics Research Associate in the Virology Research Lab at the University of New South Wales and Prince of Wales Hospital. He explains that evolution occurs more ‘neutrally’ in a stable and safe environment—changes are not good or bad for the species, they just happen.

“But if strong external pressures are applied to a population—or experienced by a population—one would expect there to be ‘sped up’ evolution,” he says. As well as the moths, Dr. Foster points to examples of domestication, where species of animals have changed over time based on human intervention.

Other examples of rapid evolution here on Earth tend to be problematic. “Some of the best examples come from pathogenic bacteria and viruses,” Dr. Foster says.

“When these organisms are treated with antibacterials and antivirals, it’s possible for ‘superbugs’ to emerge because of acquired immunity and resistance to the treatments,” he explains. “This process can also arise when treatments are applied at a suboptimal dose, so the ‘bugs’ are not all killed.” Individual organisms then develop beneficial mutations, and that’s how we get antibiotic-resistant bugs.

Evolution vs Mutation

‘Mutation’ and ‘evolution’ are words often used interchangeably in movies and TV shows. But Noor urges us to be cautious when mapping science fiction onto real-world science.

“Yes, it is true that new mutations are the raw materials for adaptive evolution across generations,” Noor explains. “But the fraction that allows this is extremely low, and any process just accelerating mutations overall in an individual is far, far more likely to be bad than good.”

He also tells us that mutations wouldn’t be “coordinated” among all of the cells in your body. “So, if Dr. Crusher or the EMH or whoever says ‘they’re experiencing a high rate of mutation’, best not to expect any superpowers or transformation to alien form,” Noor says, bringing our hopes of developing X-Men-like mutations crashing back down to our boring old Earth.

“If someone suddenly has a high rate of mutation in their body, it’s FAR more likely they’ll die or have terrible cancers than acquire any fantastic ability,” he says.

But Why Space Newts, Though?

Those incredibly stressed out by ‘Threshold’ might be comforted to learn that the creators knew they were doing something unconventional with this episode—but claim it was intentional.

In Captains’ Logs Supplemental: The Unauthorized Guide to the New Trek Voyages, Jeri Taylor, a Star Trek scriptwriter and producer, explains that the inspiration for ‘Threshold’ was breaking the Warp laws and asking: “What happens if you do go Warp 10, how does that affect you?”

“So we all sat in a room and kicked it around and came up with this idea of evolution and thought that it would be far more interesting and less expected that instead of it being the large-brained, glowing person, it would be full circle, back to our origins in the water,” Taylor explains. “Not saying that we have become less than we are because those creatures may experience consciousness on such an advanced plane that we couldn’t conceive of it. It just seemed like a more interesting image.”

I hear you if you still fundamentally hate this episode and everything it stands for. But it did show us a kind of evolution we’ve not seen much of before—there were no large-brained, glowing people with superpowers, that’s for sure.

And Taylor’s right. Who’s to say space newts don’t have some inconceivable, advanced consciousness beyond our wildest dreams? And who knows how we’d evolve if we were simultaneously at all points in space—talk about external pressure.

After all, some theories suggest that our futures won’t be filled with super-advanced creatures, space newts, or humans with superpowers and big brains, but due to a process called carcinization, everything on the planet might one day become a crab.

This reminds me of a scene in The Time Machine (the book, not the movie) when H.G. Wells’ traveler takes a trip tens of millions of years into the future. What does he find at the outer limits of time? Crabs, loads of them.

Although ‘Threshold’ might not rate highly for what we know about evolution today—or, for many, enjoyment—I don’t think we can knock this fresh and creative approach to evolution too hard.

This article was first published on June 29th, 2022 on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂