Speaking to The Hollywood Reporter during the promotional roadshow for Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, producer Akiva Goldsman made an interesting reference:

“If you think back to The Original Series, it was a tonally more liberal — I don’t mean in terms of politics, but it could sort of be more fluid. Like sometimes Robert Bloch would write a horror episode. Or Harlan Ellison would have ‘The City on the Edge of Forever, which is hard sci-fi. Then there would be comedic episodes, like ‘Shore Leave’ or ‘The Trouble With Tribbles’.”

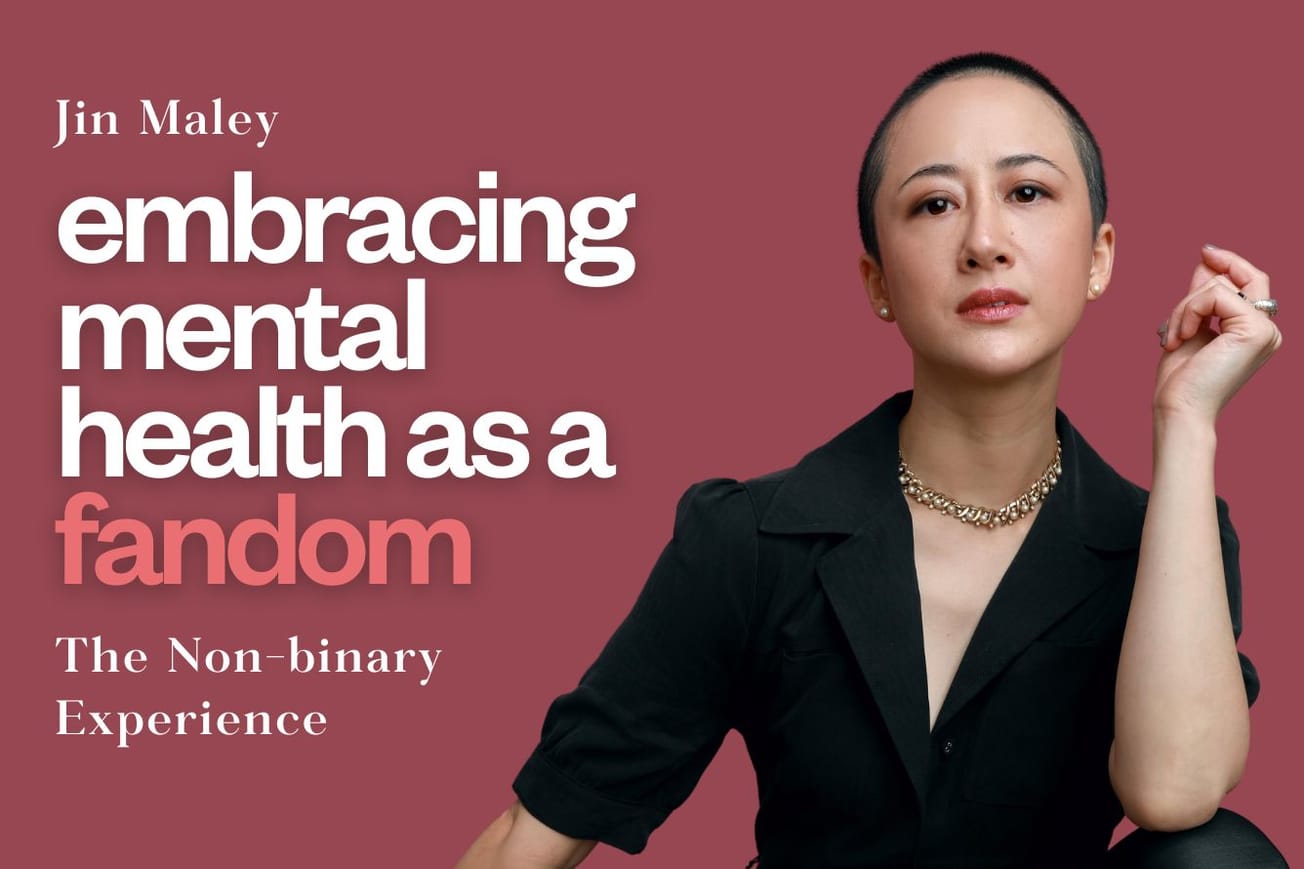

We don’t talk about Robert Bloch much, do we?

Like a hydrogen bomb, Harlan Ellison’s contributions – and grievances – suck the air out of any discussion around the various high-profile early contributors to Star Trek: The Original Series. Especially during the 1970s and 1980s when syndication and then the movies began to craft consensus from the rough cuts that comprised its canon and fandom formed. Harlan Ellison became the story that Star Trek fans told themselves about Star Trek: that it was about big ideas, that it was “hard SF”, and that Ellison’s rightly celebrated ‘The City on the Edge of Forever’ is the best of The Original Series.

That Robert Bloch wrote three episodes is a curio. An aside. An oddity. A blip. No matter how enjoyable his contributions to Star Trek: The Original Series was, Bloch was first and foremost a popular horror writer, the author of Psycho, and an influence on Stephen King. His “based on characters created by” credit can be found on Bates Motel – Ellison’s name, meanwhile, adorns Babylon 5.

A teenage acolyte of H.P. Lovecraft and his flamboyant Arkham House publisher August Derleth, Bloch’s first published stories were either inspired by his mentor or took place in the growing shared universe known as the Cthulhu Mythos. Lovecraft – for all his faults, and they are legion, was touched – and the only story he dedicated to another human, he dedicated to Bloch. Lovecraft’s The Haunter of the Dark (1935) followed a young writer called Robert Blake and was a sequel to one of Bloch’s own stories, The Shambler from the Stars (1935).

Following Lovecraft’s death in 1937, Bloch broadened his output by degrees, building on the themes he had inherited but establishing his own. He became more preoccupied with the inner workings of, well, psychos from Jack the Ripper to Norman Bates. He dabbled in straight science fiction and moved in science fiction circles, but he was – like his Star Trek episodes – an anomaly.

In his introduction to The Best of Robert Bloch (1977) – misleadingly part of Del Rey’s Classic Science Fiction series – publisher Lester del Rey acknowledged that “Science fiction was more of a hobby than a profession for him, one he pursued as more of a reader than a writer.”

And yet… Star Trek.

Weird Trails: Robert Bloch’s Road to Star Trek

It’s unbelievable a figure so important to Star Trek is so enigmatic as Samuel A. Peeples. Although associated with Westerns – as Brad Ward, he wrote “Grade-A Yarns” for Ace Books with titles like The Hanging Hills (1953) and The Marshal of Medicine Bend (1954) – Peeples was prolific in pulp fandom, appearing on the letters’ page of Thrilling Wonder Stories and Super Science Stories as early as 1940, where he invited overtures from other fans in the Texas area and desperately sought the final pieces for his Edgar Rice Burroughs collection.

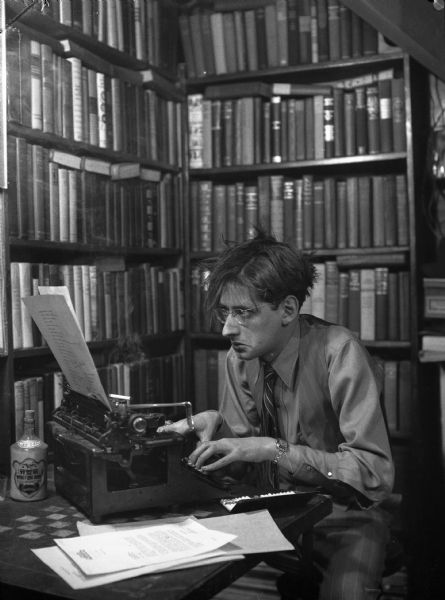

Peeples first met Bloch in 1954 at the 12th World Science Fiction Convention (in attendance Isaac Asimov, Doc E.E. Smith, Fritz Lieber, and rocket scientist Willy Ley) and the two struck up a friendship. In 1957 – having impressed the right people with his prodigious paperback output – Peeples pointed his wagon west towards Hollywood and a slew of straight-shooting shows like The Rifleman, and Rawhide. Following a persuasive long-distance telephone call and the promise of a writing gig in TV, Bloch relocated to Hollywood in 1959 and received his first of four credits on the crime drama Lock-Up (“True Stories of THE ACCUSED! THE CONVICTED! THE CONDEMNED!”).

Inevitably Bloch soon found more suitable vehicles for his talents, contributing to 10 episodes of the Boris Karloff anthology Thriller – which adapted Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper amongst other tales – and 17 to Alfred Hitchcock Presents, including one so stomach-churning that it was never broadcast (‘The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’ – S7, Ep39). Unlike later anthology shows The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, Alfred Hitchcock Presents and its expanded successor The Alfred Hitchcock Hour preferred its tales rooted in reality. All of this was grist for the bloody mill of Bloch who was as comfortable with serial killers as supernatural chillers.

Also in production at Revue Studios using many of the same crew as Alfred Hitchcock Presents was Psycho. Despite being based on Bloch’s 1959 novel – itself a loose retelling of the Ed Gein case cribbed from the headlines – he wasn’t given the opportunity to adapt the screenplay. Bloch received only $9,500 before the publisher, his agent, and the taxman took their cut but it did much for the author’s reputation, which was already growing in Hollywoodland. His gratitude to his old friend was evident, dedicating his 1961 collection Nightmares to publisher August Derleth, contemporary Fritz Leiber, and Samuel A. Peeples.

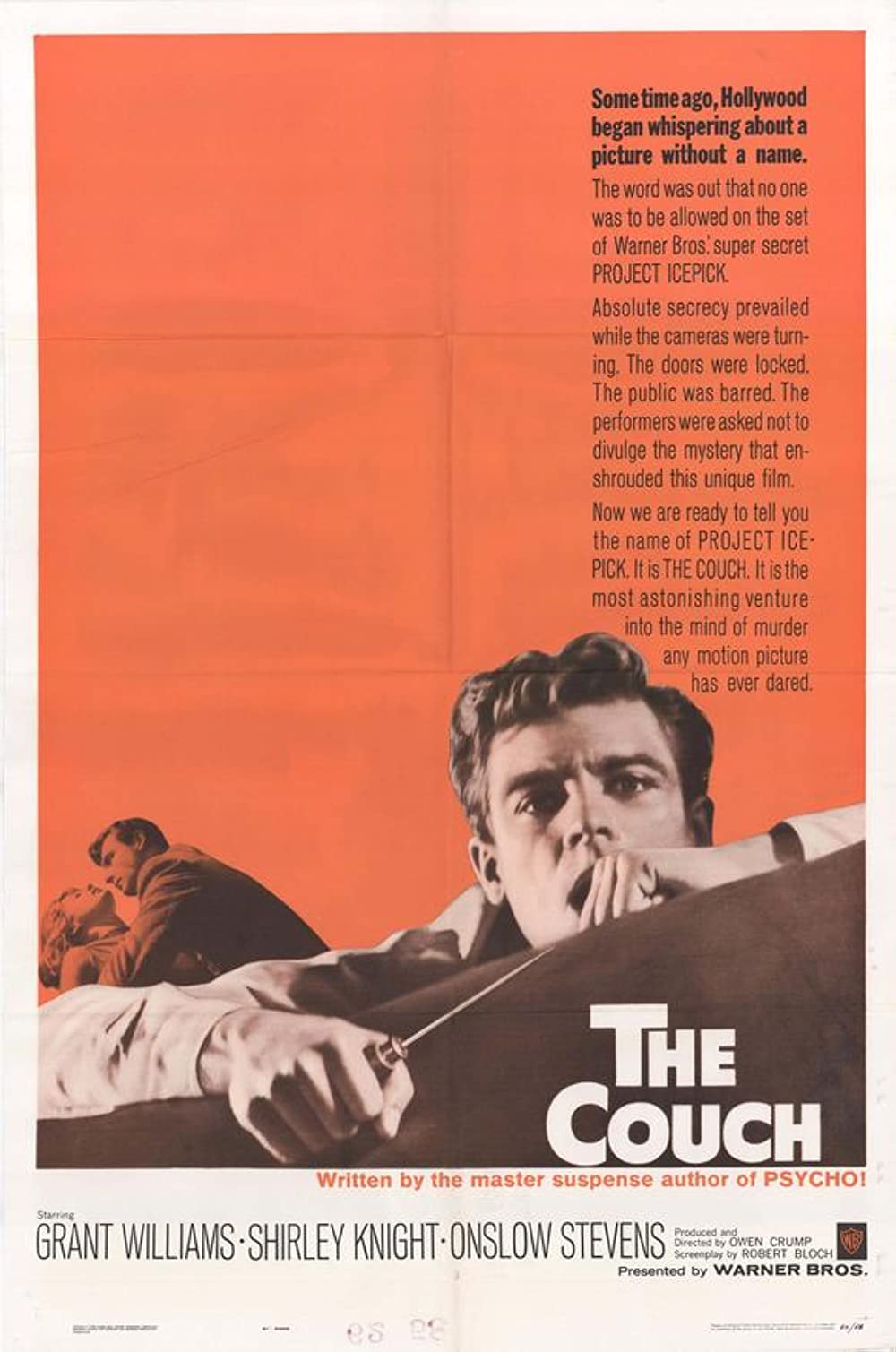

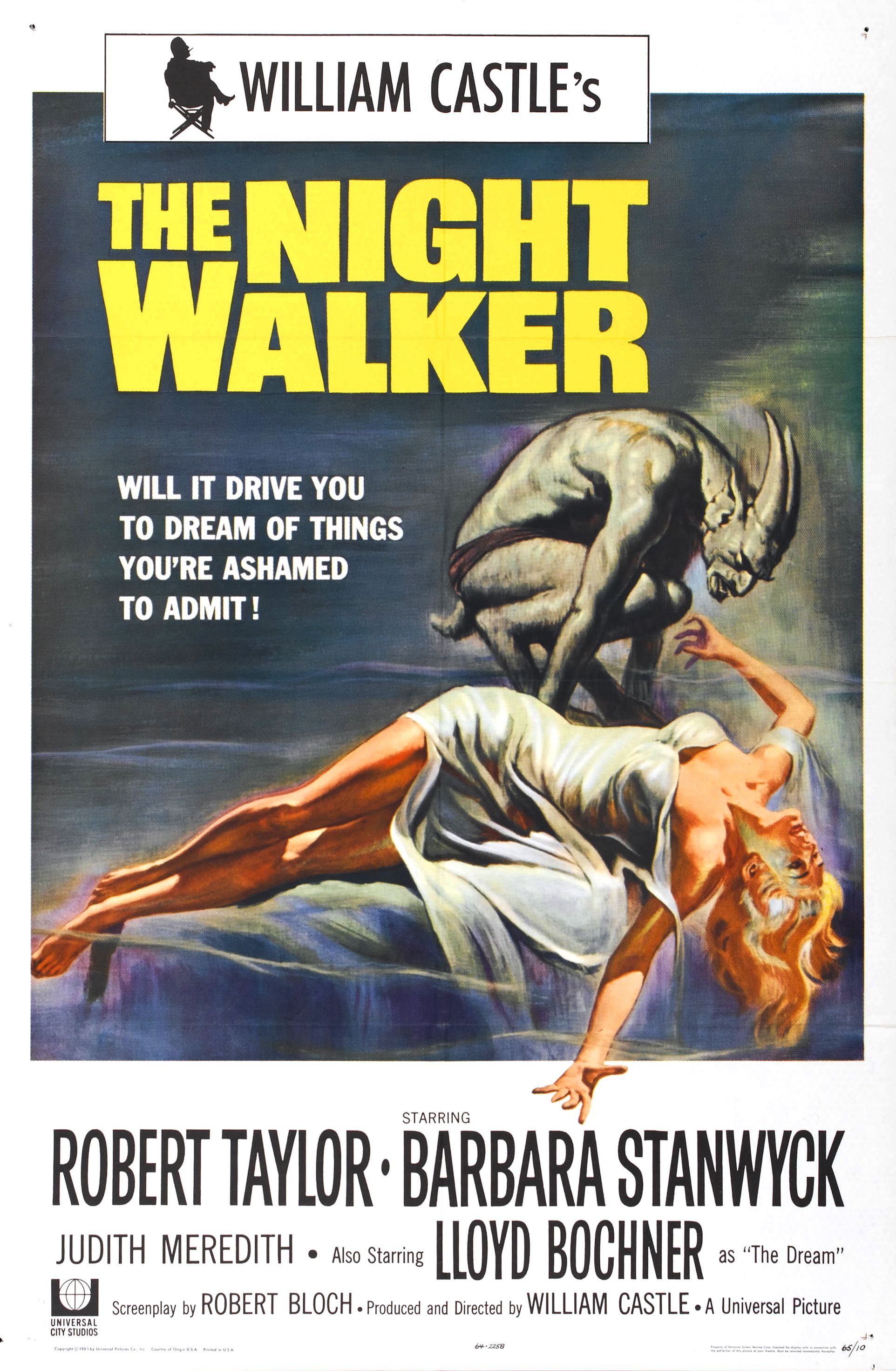

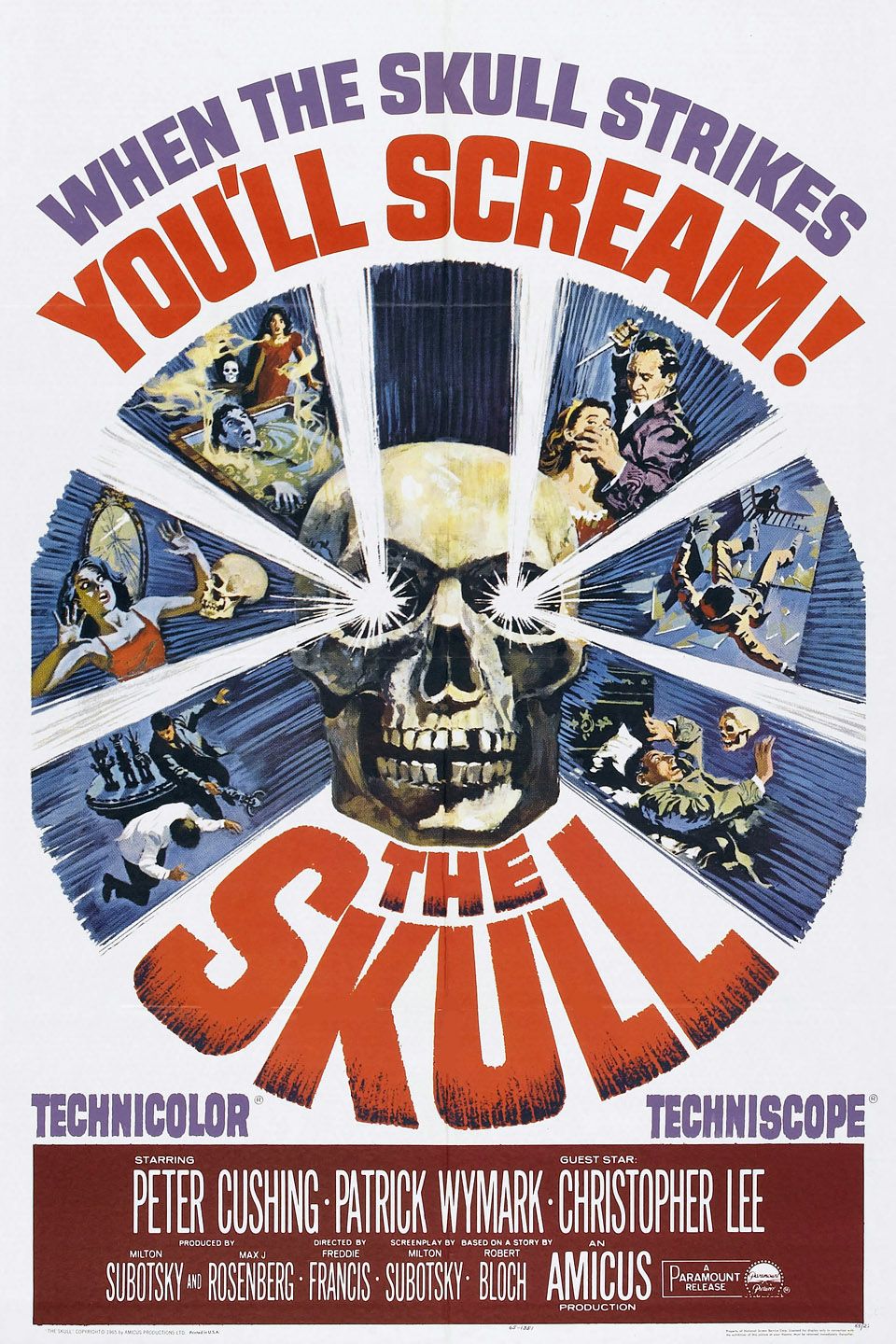

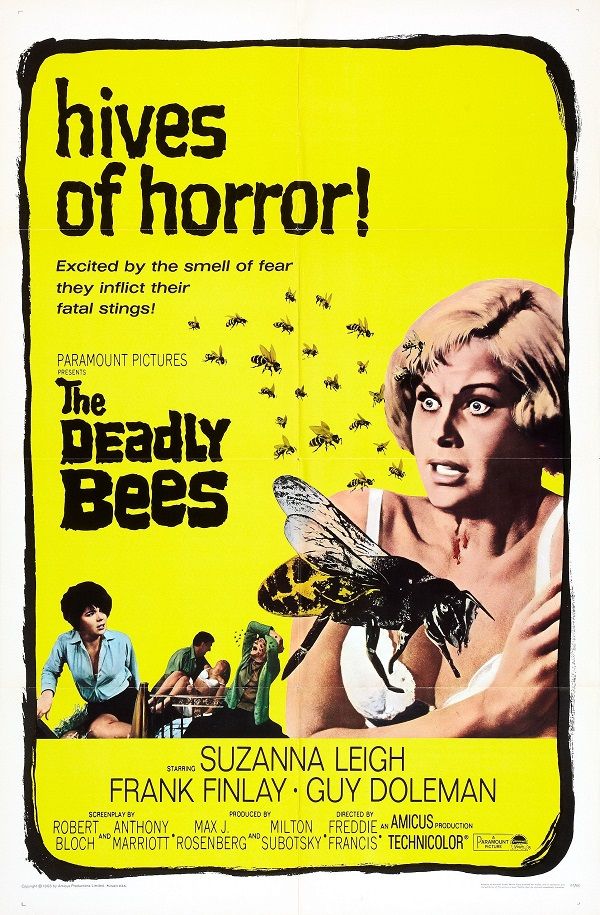

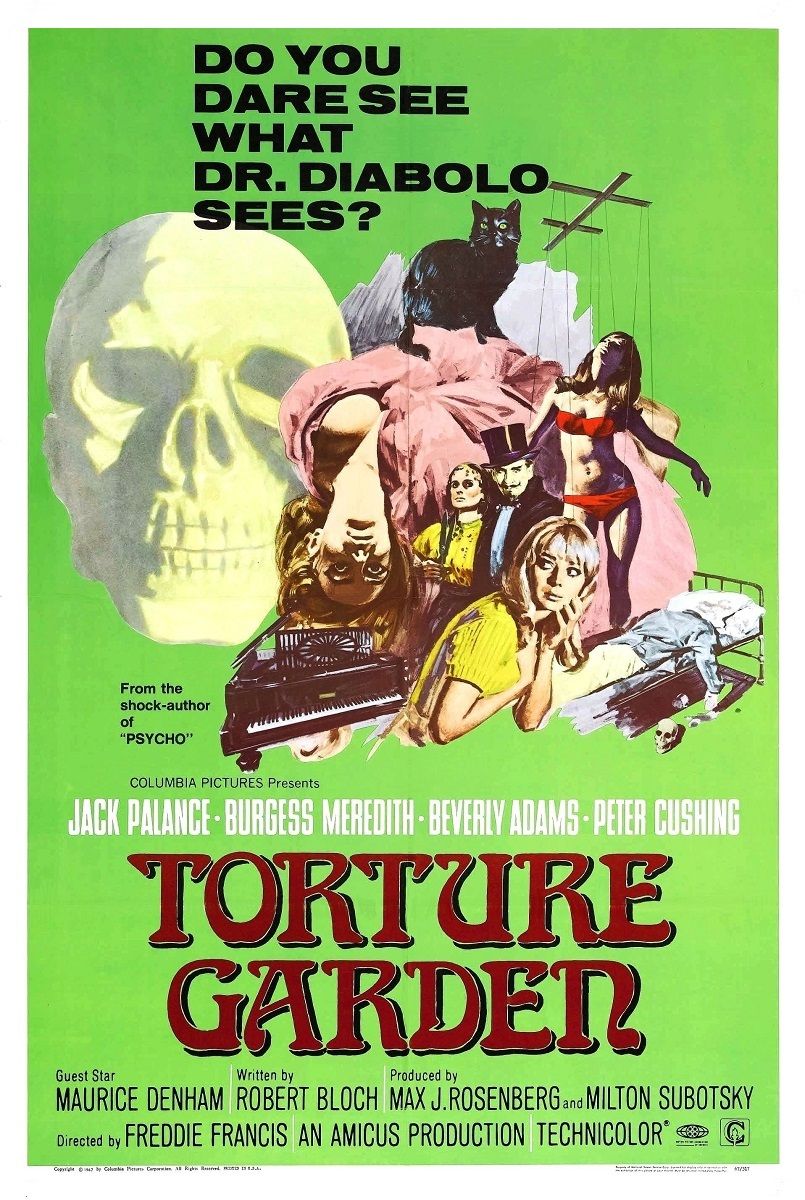

Whilst Psycho wasn’t ‘his’ movie, Bloch moved in on the big screen as well as small, selling his original screenplay for The Couch (1962), working with horror huckster William Castle on Strait-Jacket (1964) and The Night Walker (1964), and beginning a long and more prestigious association with British studio Amicus. After The Skull (1965) – starring Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee – was adapted from one of his shorts, he seized on the opportunity to work with them on scripts for The Psychopath (1966), The Deadly Bees (1966), and Torture Garden (1967) before the decade closed.

Samuel A. Peeples was also keeping busy. Another member of his friendship circle, Gene Roddenberry, was developing a science fiction show. With little knowledge of the genre himself, he made use of Peeples’ prodigious library and formidable knowledge, borrowing from him the phrase “Wagon Train to the Stars.” Roddenberry’s memos of their lunches record Peeples recommending to him eight writers, five of whom would make the cut.

Among them was Robert Bloch.

Following concerns that ‘The Cage’ – the original Star Trek pilot – was too po-faced, NBC decided that Roddenberry’s “Wagon Train to the Stars” needed a little more Wagon Train. Peeples was employed to write the second pilot and what became the third broadcast Star Trek episode, ‘Where No Man Has Gone Before’ (S1, Ep3) with all the fisticuffs and daring-do the network could ever want. A grateful Roddenberry offered Peeples a line producer role, but his saddlebags were clearly stuffed – Peebles created Custer for ABC in 1967 and Lancer for CBS in 1968 – and so Gene L. Coon entered Star Trek history instead.

Peeples didn’t stick around but his assistant-turned-screenwriting protege did. Dorothy Fontana – better known by her gender-neutral pseudonym D.C. Fontana – got her start, coincidentally, in the studio typing pool during the production of Psycho. So whilst she didn’t know science fiction, she knew Bloch. “We were turning out the pages for Mr. Hitchcock and his production staff,” she told SHOUT! Factory in 2019. “I liked it so much that the head of the typing department let me read the whole script, which was very nice of her.”

Fontana had ridden with Peeples on Frontier Circus and The Tall Man, before hanging up her harness to take a job with cop-turned-creative Gene Roddenberry on his first series, The Lieutenant. When the show was canceled in 1964 after only one season, she followed him onto Star Trek: “He got about 25 or 30 books of science fiction short stories by noted writers, and he had me read every one of those stories and break it down as to whether it might be a possible story for Star Trek that they could buy. They didn’t, but he did use some of those writers.”

“I was in the first group that was invited to see the pilot,” Bloch told Cinefantastique Vol 27 No. 11/12 (July 1996), ‘and they asked me to do one. I must tell you that my arrangement with my agent is that I never solicit an assignment, never have. They call in and I either go or don’t depending on whether or not the thing seems suitable to me.”

The Cthulhu Mythos and ‘What Are Little Girls Made Of?’

Bloch’s first Star Trek script and his only one for the first season, ‘What Are Little Girls Made Of?’ (S1, Ep8), has the Cthulhu Mythos stitched into its premise beyond the superficial thrills of having ancient android Ruk (The Addams Family’s Ted Cassidy), intone: “I was left here by the Old Ones.”

If you make Kirk a sea captain and turn the snow-caked planet of Exo III into the Antarctic then the hunt for a lost expedition feared dead, but in fact, transformed by their findings subterranean city of a long-forgotten alien race, then it’s basically a sequel to H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness (1931). The striking visual twist of the turntable that transforms an eerie husk of stunted limbs into a perfect android duplicate likewise echoes the reveal at the climax of Lovecraft’s The Whisperer in Darkness (1930):

“The three things were damnably clever constructions of their kind, and were furnished with ingenious metallic clamps to attach them to organic developments of which I dare not form any conjecture. […] For the things in the chair, perfect to the last, subtle detail of microscopic resemblance—or identity—were the face and hands of Henry Wentworth Akeley.”

Horrors abound in ‘What Are Little Girls Made Of?’, from a hapless redshirt’s fading scream as he’s tossed down a “bottomless pit”, to the severe Ruk eerily calling out to Kirk in the voice of Nurse Chapel (Majel Barrett). Then, there is Dr. Roger Korby himself, reminiscent of every ethically untethered ‘mad scientist’ from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to Lovecraft’s Herbert West.

“Do you realize the number of discoveries lost because of superstition, of ignorance, a layman’s inability to comprehend?”

Some slender comparisons can also be found in Bloch’s Iron Mask (1944), in which the French Resistance encounters the historical Man in the Iron Mask, who is revealed to be a 13th-century robot given “perpetual life, and human intelligence” by an English monk Roger Bacon. Programmed to destroy France, the Android in the Iron Mask throws in his lot with the Third Reich.

Although reportedly rewritten by Roddenberry whilst the episode was being shot, Bloch was altogether more sanguine than some of the other literary guest writers, such as Jerry Sohl who put ‘This Side of Paradise’ (S1, Ep24) under a pseudonym, and Harlan Ellison, who spent many thousands of interviews bemoaning the butchering of ‘The City on the Edge of Forever’ (S1, Ep28).

“They did that show fairly consistent to what I had written,” he told Starlog No. 113 (December 1986).

Then story editor John D.F. Black remembered it very differently, telling Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman in Captains’ Logs: The Unauthorized Complete Trek Voyages (1995):

“Robert Bloch is one of those venerables. He’s a writer with a phenomenal and enormous stature among science fiction writers. I respected him and when he came in the story was already on line; the deal had already been made when I signed on to the show. It was a story that I wanted to see what the hell he would do […] in the translation from story to teleplay. I don’t think I would have touched it. [Gene Roddenberry] did.