Director Denis Villeneuve has often explained in interviews that his cinematic goal, dream, treasure if you would like, was to adapt Dune for the big screen. But why? And why should Hollywood, or me or you, be so thick with energy or wet with salivation at the prospect of seeing not one, but two Dune films (and the subsequent series) assimilate into 21st-century pop culture? What's so special about Dune, what makes it different?

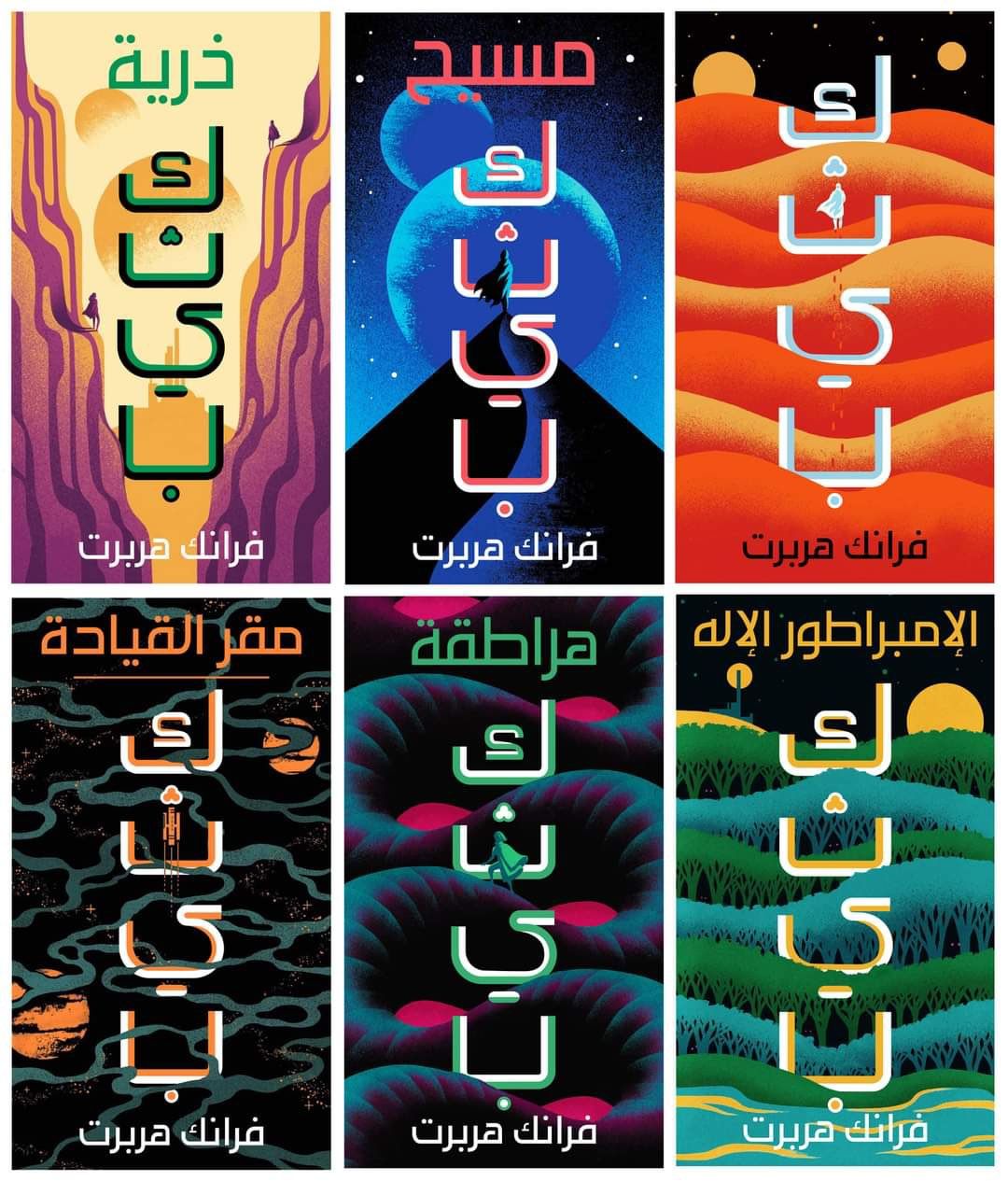

One thing dutifully separates itself from Star Wars or Game of Thrones (which it’s so often compared to). And that’s how it decentralizes western storytelling, with the aid of MENA (Middle East and North Africa) culture and traditions. It’s no surprise the director of Incendies (2010), a fiction film about twins who journey to the Middle East to discover their family history and fulfill their mother’s death wish, would be so attracted to the very literal sandbox of Herbert’s universe and messianic story. But, we must start at the beginning, the root of this inspiration, the book itself and its author, Frank Herbert.

The Cultural Origins of Dune

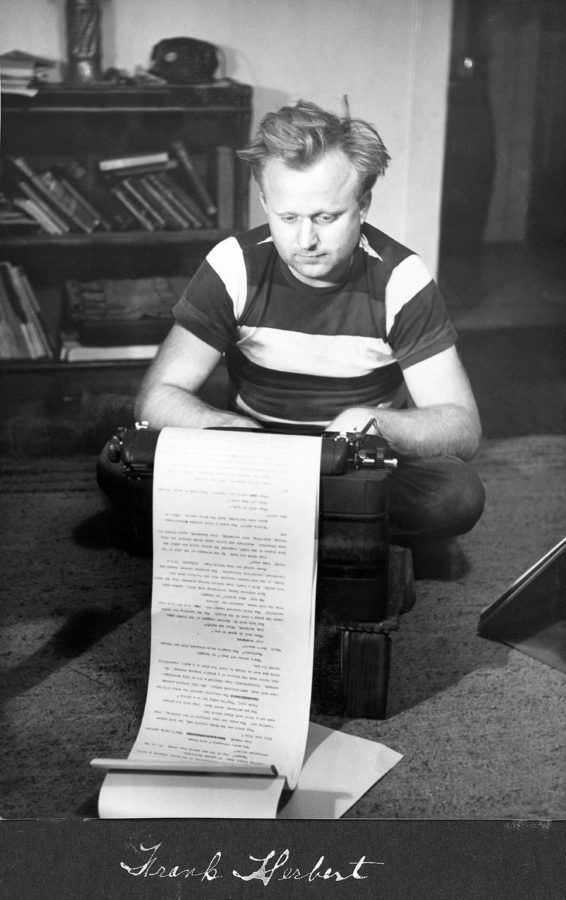

Frank Herbert is as American as it gets, from Washington and born on a farm just after the Great Depression, he ran south to Oregon because of his troubled home life, where he would let his interests and curiosities direct him. That part is important. One of those was photography, which took him to the US Navy in the Second World War for six months before writing (and a family) would become his most recognizable of loves. He would spend years writing political speeches for Guy Gordon during the McCarthy era, short stories, editing magazines, and studying ecology, engineering, Zen Buddhism, and politics.

He was raised for some time on the Quileute Indian Reservation by a man from the Hoh tribe. His life went on, his interests never ceased instead they deepened. In fact, the initial spark that led to the famous story of Dune was in fact, Herbert’s commission to study dunes in the deserts of Oregon. His adopted home. Flushed with his taste for psilocybin (magic mushrooms) and the expansive latitude and unforgiving heat of the Oregon dunes in Florence. He would be struck by a story he wouldn’t be able to shake, one of the giant Sandworms, a native tribe, the expensive spice Melange, and the jihad of the one, us, and the rest of the universe would come to know as Maud’Dib. That story would become Dune, and yes, according to himself he totally ignored the original commission in favor of this science fiction, which may have seemed absurd at the time.

In an interview from 1969, Herbert would explicitly note he read over 200 books in his studying for Dune, books that would range across the spectrum of religion, ecology, culture, history, engineering, and so on and so forth. He cheekily, admits, that his curiosity and openness to the world around him were what inspired him. After all, he was a poor farm boy from the northwest. You can’t blame him. All of these influences would fold themselves into his story, this approach to writing and storytelling is what legal historian Haris Durrani calls, “syncretic”. He credits knowledge of this term to a friend, New York Times journalist Evan Hill. Many, to make one. In fact, many great artists or storytellers do this when they create new original works.

As writers and creators know, nothing is truly original. What differs from one to the other, is the diversity of that syncretism. In Herbert’s case, it’s extremely broad and just as importantly, daring in its approach.

That is, by drawing from many Eastern and MENA cultures from the structural DNA and language of his story, which is an American English language book set to be read mostly by that demographic, at least upon release at the time in the mid-20th century. Quite aggressively, forcing white Americans to familiarise themselves with the meanings, semantics, and feelings of these cultures. So often, the word “jihad”, which roughly translates to “struggle” is connotated with shame or spite in 21st-century media.

For so long, our stories have twisted and turned the idea of MENA culture and language into something every person in the Western world should be inherently cautious of. But for example, when the protagonist, Paul Atriedies’ journey of growth and power becomes known as “jihad”. It extracts those terms from cultural specifics and our perceived pre-history, to create a new, less sensitive meaning. One that is different from those prescribed by the structural political forces above us. This is not entirely true, in further reading of the Dune books, jihad would become a politically charged term, as a product of Paul’s horrific actions.

This could be construed as cultural appropriation, however, Dune’s focus never prioritizes one culture, and to say so brings us around to the theme of syncretism again. The language, manner, and lore of the Dune universe is an amalgamation of so many different cultures and religious ideas, that if there is anything Herbert is guilty of, it’s knowledge appropriation, not cultural appropriation as Durrani describes. He sews so much of his research and interest into the book, that all of it in some sense has been misused, or rather a better way to express, “displaced”. It’s not so different, from George Lucas’s inspiration of Japanese culture and spiritual ideas to create the foundation of Star Wars (1977), except Herbert’s excavation is much, much, more thorough and broad.

Dune isn’t exclusive to MENA ideas, plenty of references to western religion and history are made. “Messiah” and “crusade” are terms tossed around, albeit with less frequency than the Eastern references. Though, Haris admits Christianity is not necessarily ‘Western’ either. Herbert’s interest in these ideas is less potent. This isn’t to impress, that this kind of appropriation is better or worse. It’s hard to judge, as it depends on the background of the reader and how much they experience from the story.

As for the aforementioned Star Wars, there are plenty of souls who’ve no idea it’s related to any history, or culture in reality. Those who don’t know that Stormtroopers are named after the Imperial German shock troopers of the First World War… however, an audience’s interaction with the story is all but guaranteed once they begin reading. That interaction in itself is what provides the human brain with a foundation to begin to understand new ideologies. Every time the brain interacts with the story, we consciously make ourselves receptive, in other words, our guards come down and we relinquish control, thus inviting the storyteller to teach us something worthwhile in exchange for our attention.

So, syncretism and knowledge appropriation, what does this mean exactly, and how does this relate to Western storytelling? Knowledge appropriation, in this case, could arguably be traded for orientalism. Edward W. Said defined orientalism in his 1978 book of the same name as “the basic distinction between East and West as the starting point for elaborate theories, epics, novels, social descriptions, and political accounts concerning the Orient, its people, customs, ‘mind,’ destiny and so on.”

Most maps in the USA have America in the center, the other continents surround it. This is not how maps are made in Europe, or other parts of the world. But Americans see themselves at the center of the global story, the protagonists. This filter creates a romance with everything around America. With many other cultures taking a backseat to this, over time, this lens or filter becomes invisible, most Americans don’t know their maps are different. This comes back to our sensitivity as an audience to MENA culture and traditions. Judaism, Buddhism, and Islam, all seem like exotic trips to our Western regularities. So often pertained to as the ‘other’ seen through the eyes of some character or place we can relate to as if it were fictional tourism.

However, Herbert’s syncretism and knowledge appropriation bucks this trend massively, especially for a book written in the 1960s. “Anyone can write about anything, just put in the work. It’s very clear that he did the work.” Durrani explains carefully. Forcing young white boys to pronounce words like “Gom Jabbar”, “Kwisatz Haderach” and “Sardaukar” is a far cry from what I expected when I picked up the book about four years ago. I still think about how I played with these words and sounds in my mouth when I first read Dune, it felt like I was learning a new language.

The term Gom Jabbar originates from the Qur’an, where it appears as “qawm jabbar” but its meaning is disputed. A name for a tiny weapon in Dune which appears in one of the story’s earliest moments (during the humanity test Paul undertakes), is lifted from a significant phrase from the Islamic holy book. How often can you say the same for Game of Thrones, or Star Wars? It’s certainly a far cry from “lightsaber” or “blaster”. This entry point becomes a path for readers to begin assimilating some knowledge of Islamic ideas through language. Arguably, language is the cornerstone of any culture. Communication leads to understanding. Islam is a religion so often demonized and ill-represented, sometimes swapped or traded for Christianity in storytelling, as if religions were simply coins. They’re all different but express the same thing. Which is simply untrue. These aspects of knowledge congregate to create a syncretic approach to Dune.

Rewiring How Our Brains Experience a Story

We’re brought to another aspect of Dune’s storytelling, that’s representation, race, and ethnicity. Race, as we’ve come to know it, doesn’t exist in reality. But in Herbert’s sci-fi saga, what’s the point of considering someone’s race when humanity has expanded to the point of rivaling the processing capacity of a computer and an obscenely fat and grotesque body of Baron Harkonnen can float around the room? Haris makes a strong case that rejects the exclusion of differences that reflect our current society, “I think his treatment of Paul and the Fremen is in large part an interrogation of whiteness and brown/blackness.” Race is an idea invented by a human being in our timeline, after all, there’s only one human race that’s very obvious to see. What we’re exploring is ethnicity and its degrees of complexity.

Herbert uninvents race in Dune. This being as it is, all characters we’d recognize as typical humans like us, are referred to as having “olive skin”, including Duke Leto and the Atreides family. In fact, for a sci-fi story to be believable, it’s required to have a diverse and ambiguous cast. The original Star Trek series is a perfect example of that. It fathoms a post-racial environment, where humans are less interested in differences and more interested in similarities. Coupled with Herbert’s persistent interest in MENA culture and religion, it’s not necessarily true to say the cast of Dune should be of MENA heritage, however. It is necessary to point out that at least some of that cast should represent the route of the story’s inspiration in this human world that we do know and are familiar with.

Your friendly reminder that Dune was inspired by the Middle Eastern oil crisis of the 1960s and borrowed heavily from Arab, North African and Islamic culture but the new film, despite being shot in the United Arab Emirates, does not have a MENA actor in its main cast.

— Hanna Ines Flint (@HannaFlint) April 14, 2020

It’s truly, utterly bizarre, that aside from the Persian-American David Dastmalchian who plays Piter de Vries, not a single one of the lead cast from Villeneuve’s first film is of MENA descent or heritage, and at the time of writing only two of the cast of Dune: Part Two – Swiss-Tunisian Souheila Yacoub as Shishakli, and the British-Iranian Alan Mehdizadeh as a Weapon’s Master. Whilst there is an increasing number of ethnically ambiguous cast members, “olive-skinned”, like Oscar Isaac, Jason Momoa, Zendaya, Dave Bautista, Stephen McKinley Henderson, and Javier Bardem. Leit Kynes has been gender-flipped and played by Black British actress Sharon Duncan-Brewster, in the book Kynes is described as mixed-race, half Fremen, half off-worlder.

In fact, just a little research and you’ll find many of the supporting Fremen actors are of African descent. A step in the right direction but only a step. The lead cast is still representative of what Hollywood thinks is palatable. These actors are already box-office hits individually, and Hollywood is comfortable letting them take the center stage behind its Western lens. After all, if no one knows where they’re from exactly, it is easier for them to sell. Ambiguity can act as a shade to hide behind. Haris points out, “They haven’t mentioned Islam at all in the marketing.” The idea of which worried us both.

If we take this ambiguous cast and syncretic storytelling style as it is, the sum of its parts is still something that resonates with how our brain experiences a story, especially one of this size and scale. When the first round of viewers turned on Star Trek: The Original Series in 1966, how they experienced a story changed remarkably. Here’s one that didn’t concern itself with the petty ‘isms’ Western culture was structured on, we had a black woman (see Uhura played by Nichelle Nichols) in space while black people would still suffer from the apartheid in South Africa until the end of the century. And that matters. The storyteller knows this part of your mind is shut off and they’re taking advantage by forecasting a way of thinking in your brain. You must accept Uhura, regardless of her skin – otherwise, how could you apply yourself to the story of Star Trek?

Frank Herbert’s Dune takes up a similar mantle being made within those same few years but what it’s asking you to commit to is much more complicated than the casting of Uhura. There is no ambiguity in Nichelle’s casting. She’s clearly African-American. In Dune, ambiguity is everywhere. When Paul joins the Fremen, his eyes take up the same blue-on-blue tint as their people, as do other characters. It’s an ecological side effect. I imagine a young Frank Herbert losing himself on a native reservation. Was it his experiences that inspired this? Or is this a comment on appropriation? Paul assumes power quickly, as an imperialist would a colony. To assume his background intelligence was somehow superior to theirs before he truly knew their ways. When European men arrived on the beaches of foreign lands, they claimed their superior intellect and fate which brought them there.

His iteration of a hero’s journey is ambiguous too. Paul is more like Michael Corleone in The Godfather than he is like Jesus of Nazareth in the New Testament. His turn from innocent victim to godlike omniscience is terrifying. “He keeps making you ask questions. He’s positioned as Lawrence of Arabia, yet in another way, he is the prophet, Mohammed. You could say it’s a critique, you could say it’s not.” Durrani expels the ideas excitedly and we confirm that Dune has many contradictions, between what’s written, and what’s not (check the appendix), what were Herbert’s beliefs in reality, and his beliefs in the book. Positioning Paul as the sympathetic protagonist (or antagonist depending on how much of the series you commit to) is probably one of the most delightful literary tricks Herbert pulls. Remember this is 1964. All white boys were seen as heroes after two world wars for an economically undefeated America. Vietnam would change that. Having the white savior you rooted for on page one become a cold-blooded demi-god with the ability to kill millions wasn’t necessarily the kind of book you’d sell and expect to sit right for white Americans. I think victims of colonialism won’t have a hard time imagining that kind of arc though.

The Fremen, first referred to as “savages” by those who know little about them are represented as probably the most intelligent and resourceful of all the factions portrayed in Dune. Despite a history of a plundered homeworld, they still live in large numbers and are adorned with respect by those who know of them. We certainly know they aren’t the savages we’re expecting when Paul is taken in by Stilgar and becomes known as Usul of their tribe. Herbert is actively taking our hands and asking us to inherit a new culture, new information, and new religion. And we do, pretty quickly. If anything it proves there is strength not only in knowledge but in communal knowledge and specifically, the learning of it. Paul isn’t the only one to join the Fremen, and so does his mother, Lady Jessica, and paternal warrior, Gurney Halleck.

The Progressive Legacy of Dune

It took writing this essay, my research, and talking to Haris. To have some wave of conclusion come over me, whatever Hebert thought about the world didn’t matter much. He was clearly very enthusiastic about learning it and probably spewed out much of what he learned into his own version of a holy book; he so often referenced other holy books and scripture, it’s the only way to come to terms with all its contradictions, intratextual and intertextual references. Who is this all for? Well for himself. Or himself at the age he was when he ran away from home at least. I admit it’s a comforting, somewhat patronizing way to look at an artist’s work. Nevertheless, we must remember Dune is a book first sold in the United States by a publisher, in English. And a book’s job of entertainment or information is always second to how many copies of that can be sold or read.

The structural forces above us provide a hefty barrier between us, the audience, and the works that could’ve been. I explain my fascination with Dune comes from the fact I’ve never seen or read or heard of a story in the shape that Dune takes, and it was written almost 80 years ago… there’s a phrase, you know the one. “One small step for man, one giant…”– yeah, you get the point. Dune is just a book, maybe Herbert’s holy book. But still, it’s one of the first syncretist stories for the modern world. Truly a story of the future for the future, whose focus is how we communicate, how we evolve, and most importantly, what humanity wants. Is it Spice? A savior? Evolution?

Call it science fiction, call it religious speculation. Whatever it is, it’s definitely more than most. More than most stories, as well as the reproduction of many stories and a critique of these same stories. It is and it isn’t. It’s Dune. Frank Herbert’s Dune. Whether or not a Western man from the Midwest can decentralize storytelling from his own power structure, he certainly tried very hard to. Probably harder than anyone else has. Legendary’s familial and non-committal approach to marketing Dune (2021), with all its Islamic wording, political critique, and ecological commentary hidden behind the sculpted face of a young charismatic Timothée Chalamet is a fitting example of how giant Herbert’s leaps were, and how small the steps of storytellers in Hollywood and Western culture have been since...

This article was first published on October 8th, 2021, on the first Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂