Frank Herbert’s Dune has long been thought to be an “unfilmable” book – and its long history of cinematic adaptations has tended to bear that out.

After failed attempts to get a Dune movie off the ground by filmmakers like Alejandro Jodorowsky and Ridley Scott, David Lynch's 1984 version (picking up on their prior efforts) feels like the end of a game of telephone, messy big-budget studio film from an auteur more interested in the surreal and intimate.

Then there are the twin Sci-Fi Channel (now Syfy) miniseries from the 2000s, courtesy of writer/director John Harrison; adapting the first three books into 12 hours of television, they certainly do more to flesh out the world of Arrakis and the path of the Imperium than Lynch could do with millions of dollars and two hours. But it suffered from its budget and, again, the difficult nature of adapting such dense material.

Denis Villeneuve’s version, Dune: Part One (2021), is the latest attempt to adapt Herbert’s vision to the screen, and it’s certainly one of the most sprawling, modernist approaches to the material you could imagine. But for all its spectacle and star power, it's got its own problems finding a human element in all of Villeneuve’s arched-brown minimalism.

People often cite the convoluted, spice fog-thick worldbuilding of Herbert’s universe as a central reason Dune adaptations fail. (Heck, the 1984 theatrical release featured a glossary handed out to patrons who wouldn't know their CHOAMs from their carryalls). But my (perhaps spicy) take is that Dune's difficulties in heading to the screen, whether big or small, lies in the book’s characters – specifically, its protagonist, Paul Atriedes.

Dune is a story about ideas and history, about the ways individuals struggle to make an impact on the broader trajectories of time and inertia. Ostensible, Dune is a coming-of-age story for Paul, a young lad thrown into a grand adventure to seek out his destiny. But it’s also a deconstruction of that same hero’s journey, a tale of what happens after the hero saves the universe and takes the throne – and the lives that will be lost in the process. That makes the book a hard block of marble to carve into the dimensions of a standard space adventure film.

It’s also a struggle for the actors who’ve been tasked to plat him: Paul, after all, is a superbeing, albeit one who struggles against that path that has been laid out for him. He’s more stoic and sure of himself than the kind of underdog protagonist we typically get in these kinds of sci-fi stories; he may have the special powers and unlikely destiny of a Luke Skywalker, but not his humble upbringing.

Between the huge emphasis on lore, and the relative blankness of Paul as a character, it’s hard to make the part stand out on-screen amongst the sprawling scope and larger-than-life characters (in the Baron’s case, literally) that surround him. But paired with each attempt’s particular circumstances, and the visions of their respective directors and actors, each Paul we’ve seen on screen has had their share of ups and downs in the role.

Kyle MacLachlan in David Lynch’s Dune (1984)

One of the major hurdles for any Dune adaptation is age — in the books, Paul is in his mid-teens, a boy-king whose youth belies incredible wisdom and the horrifying power that lies just beyond his grasp. But that doesn’t work as well in sci-fi film and television production; kids have to play by different union rules with shorter work hours, and oftentimes may not have the emotional depth and complexity needed to carry out such a gigantic starring role.

As such, both the Lynch and Sci-Fi Channel versions age Paul up from his teens to his early twenties, which brings us to Kyle MacLachlan. A talented actor in his own right, the then-24-year-old MacLachlan was plucked from obscurity by Lynch after a casting director saw him play Tartuffe in Ashland, Oregon; Dune is his first film. While Dune would flop (and get MacLachlan’s career off to a rocky start), he’d recover nicely and settle into a robust career as a character actor, oftentimes with his new collaborator Lynch in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks.

Lynch’s take on Paul, however, gives MacLachlan little to work with. Lynch’s films often feature airy, aloof performances that hew more towards the absurd, which makes the cast of his Dune feel more alien than any of the following adaptations that would come. MacLachlan is a particular casualty of this: His Paul is stiff, wooden, uncomfortable, uncertain eyes hidden under a mop of thick, feathered ‘80s hair.

On a certain level, it works for Lynch’s version: Even within the weirdness of Herbert’s universe, Lynch’s take on the material takes bizarre turns, from S&M heart-plug Harkonnens to stillsuits that look like outright leather-daddy fetish gear. (Let’s not even touch the ending, which proffers up a magical rainstorm to bring water to Arrakis.) As such, MacLachlan’s bewilderment in the role serves nicely as a conduit for our own confusion, the audience taking in the strange sights right along with him.

But MacLachlan is also hampered by Lynch’s attempts to translate the book’s heavy reliance on internal monologue to the screen: half his dialogue is relegated to gauzy voiceovers dictating Paul’s emotional state, whispered as if he’s doing an ASMR video. (“The worm is the spice. The spice is the worm!” *crinkles a candy wrapper next to the mic*) When he’s not doing that, the wild emotional swings of the script feed him giant slices of scenery to chew, particularly in the rushed third act that speeds through Paul’s time with the Fremen and his ascension to the Kwisatz Haderach.

It’s a performance, and a film, more indebted to Star Wars than Lynchheads might want to admit, and the Luke Skywalker bleedover makes Paul suffer as a result. Where the book is, as we’ve mentioned, a cautionary tale about the paths of savior figures, Lynch’s version plays Paul’s ascent without a hint of irony. There’s no hand-wringing about the jihad Paul’s rise will herald, no troubling implications for his supremacy over the universe. Atreides and Fremen good, Harkonnen and the Emperor bad; stab Sting before he can pull a poisoned blade out of his metal bikini. Bing, bang, boom, galaxy saved.

With that nuance gone, there’s little for MacLachlan to do besides delivering his hokey dialogue with all the sincerity of a zealot. His Paul is the one most suited to an unironic, surface-level read of Dune as a straightforward sci-fi adventure — a boy coming to manhood through the rightful fulfillment of his destiny as the savior of the universe. This not only makes him boring, it makes his version antithetical to the very ideas at the core of Herbert’s novel.

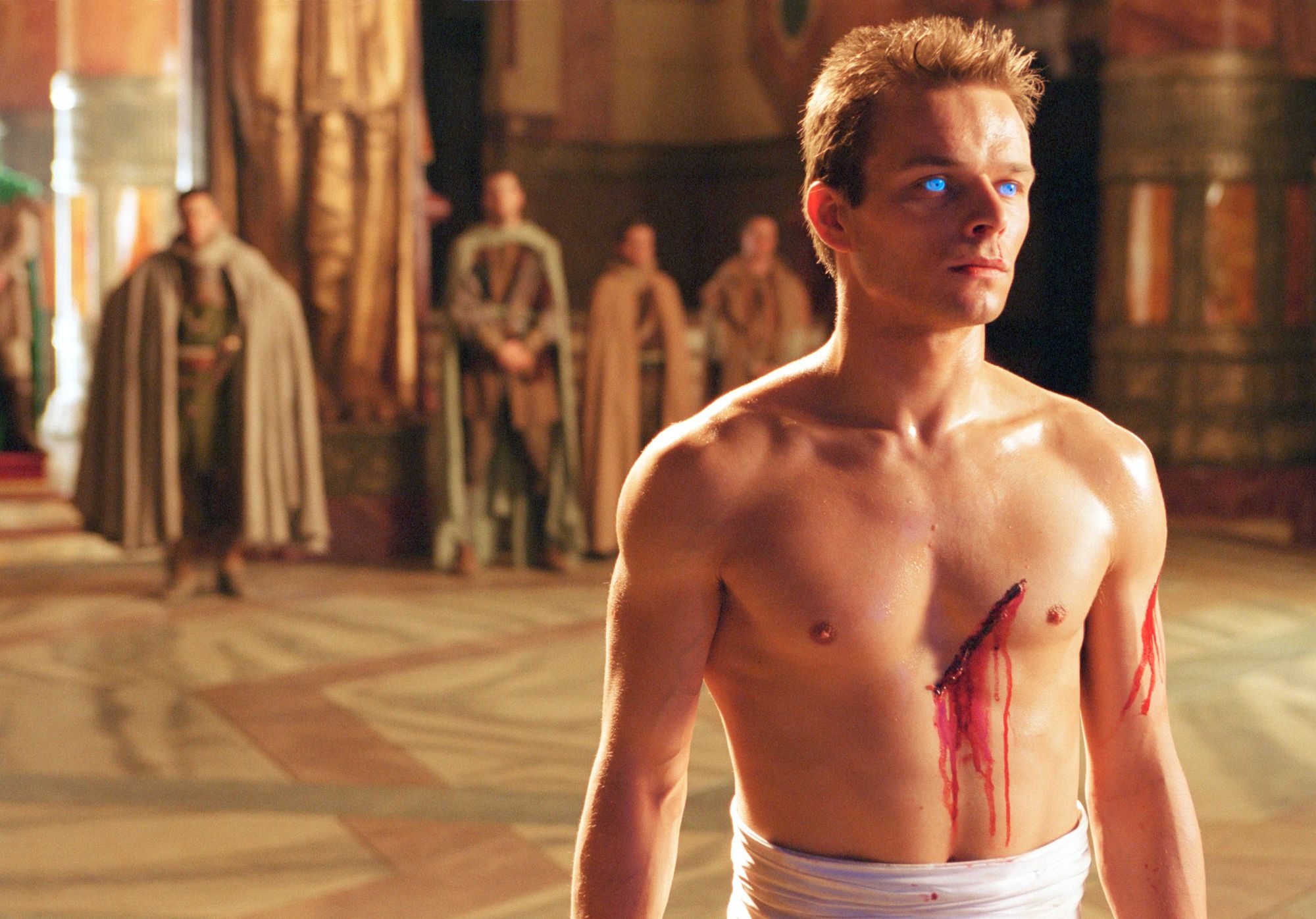

Alec Newman in Sci-Fi Channel’s Dune Miniseries (2000)

Given Lynch’s failed attempt to smoosh the entirety of Herbert’s 600-page doorstop into a two-hour film, it stands to reason that the book (and Paul) would be better served in miniseries format. And to its credit, John Harrison’s three-part adaptation of Dune comes the closest to capturing the political machinations and prophetic warnings of the novel; its script is sufficiently sprawling and dense while remaining innately accessible to 2000s TV audiences, which is probably why it was the highest-rated Sci-Fi Channel premiere to date.

But it suffered from the limitations of basic-cable budgeting, taking place in an era before prestige dramas and big-budget television like Game of Thrones were the norm. Even with its sizable budget at the time, it still wasn’t enough to capture the sprawl of Arrakis in any kind of photorealistic form. This also meant there wasn’t a huge budget for the cast, which meant that, apart from one big-name like William Hurt, the dramatis personae was filled with dedicated English character actors and the Czech Republic’s finest day players.

In the middle of it all was Alec Newman, a fresh-faced Scottish actor for whom Dune was also one of his earliest roles. Like MacLachlan (and Chalamet, who we’ll get into later), he was around 24-25 when he took the part, but unlike them, he had far more runway to learn and play the part of Paul Atreides.

It’s fascinating to watch Newman’s transformation across the three parts of the miniseries, which truly spans years and forces the actor to ‘grow up’ in a way. In Part One, he plays teenage Atreides-heir Paul with a squeakier voice, hunched shoulders, matted-down short hair, a petulant brat who doesn’t understand why the maternal figures around him (Jessica, the Reverend Mother) treat him with such disdain. But as the House of Atreides falls, he grows close to the Fremen, and settles into his role as Messiah, Newman speaks with quieter certitude; his hair grows wilder and his stance more regal. This Paul gets more chances to wrestle with the pain and burden of leadership, and the ostracism that comes with being an outsider to Arrakis.

With the script as close as it could potentially be to capturing the intricacies of Paul’s character, the shortcomings, it must be said, unfortunately, fall more on Newman’s performance. Unlike world-class actors like MacLachlan and Chalamet, Newman has fewer tools to parlay in his performance as Paul; his line deliveries more wooden, and his facial expressions a bit more unsure. He has trouble wrapping his mouth around some of Harrison’s more baroque dialogue and struggles to build chemistry with many of his costars.

In many ways, Newman himself feels like Paul within the context of Dune’s production — a boy uncertain of his responsibility as the lead of this giant cable network miniseries, and it shows in the nervousness of his performance. He feels too old for the petulant Paul to not read as irritating; he feels too young to sell the cosmic weight of Paul’s boy-messiah status. It’s a frustrating dissonance between the gifts of the script and the limitations of the production itself. One wonders whether he’d done better with more resources or a more expertly-honed cast around him.

That potential certainly bears out in Children of Dune, whose first part hews largely to Dune Messiah and keeps Paul as lead. Newman feels more seasoned in the role, a bit more grown-up, wearied of the massive burden his crusade has placed upon his shoulders. Newman’s innate dourness as a performer lends itself well to a man who’s conquered the universe but understands that his moment on top is soon to pass. Unfortunately, that’s overshadowed by the incredible star power that James McAvoy brings to Leto II in the following two parts, contrasted starkly by Newman’s goofy, gravelly take on a post-exile Paul, blinded by a stone burner and forced into the deep desert as a mercurial oracle. Newman can’t help but suffer in proximity.

Timothée Chalamet in Denis Villeneuve’s Dune (2021)

This brings us to the golden boy of the hour: Timothée Chalamet’s take on Paul Atreides in Denis Villeneuve’s 2021 take on Dune. Right away, Chalamet is both blessed and cursed in the role. The good news is that Villeneuve’s take is an enormous, big-budgeted affair with all the top talent Hollywood can muster at its disposal. He’s surrounded by an enormous cast of A-listers (Oscar Isaac, Rebecca Ferguson, Jason Momoa), captured by Grieg Frasier’s monochromatic but striking cinematography, and costumes and production design that capture the kind of brutalist weirdness that we could have expected all the way back in Jodorowsky’s abortive attempts.

The bad news? Villeneuve is only adapting half the book. The title card for this one reads Dune: Part One, and it feels like it: understanding the rushed nature of Lynch’s version, but knowing they don’t have the storytelling space a miniseries offers, Villeneuve opted to split the book in twain, offering this first half of the story in two and a half hours.

For Paul, and Chalamet especially, this means that Paul’s journey is truncated severely; we only get to see him as a boy coming to Arrakis, just barely glimpsing the future of his destiny as his family is destroyed and he and his mother seek the refuge of the Fremen. The final line of the film comes from Chani (the girl of his dreams, played by Zendaya in essentially only the final 15 minutes of the picture), who tells Paul, “This is only the beginning.” Truer words were never spoken; it’s hard to even gauge Chalamet’s take on Paul in a story that feels this incomplete.

What we do have, though, evinces one of Villeneuve’s major hurdles with the material: it’s so focused on lore and implication that it doesn’t have time for the people it depicts on screen. As Paul, Chalamet is mostly a mope, a sullen corpse-boy who speaks half his lines as if his jaw is wired shut. He looks the part, that’s for sure; while he’s the same age his predecessors were when they took the role, his gaunt cheeks and slight frame make him look much more like the too-wise teenager Paul from the books.

But there’s none of McLachlan’s twinkle in the eye, though he better captures Newman’s adolescent angst. There’s an intensity, a self-seriousness to Chalamet’s performance that makes him hard to read, barring those too-rare scenes where he bonds with Jason Momoa’s gregarious Duncan Idaho.

Otherwise, his performance is filled with a sense of emotional constipation, as if he’s holding in the heft of all of these expectations within his tiny, lithe bones lest they burst from him in a ball of fury. (It’s an interesting approach, especially when it finally comes out in a rant to Jessica in a stilltent after they’ve just escaped the Harkonnens: “You made me a freak!” he squeaks resentfully, in pure “I didn’t ask to be born!” energy.

How to Do Paul Atreides Right

So far, all three Dune adaptations have yet to disprove the theory that the book is truly unfilmable, right down to the inscrutable nature of its protagonist. Whether MacLachlan, Newman, or (what we’ve seen of) Chalamet, Paul Atreides-turned-Muad’Dib is a character whose innate essence just hasn’t been fully cracked on screen.

Is there a way to do Paul justice? It’s hard to say, really. He’s an innately novelistic character, one that doesn’t lend itself easily to the rhythms of genre filmmaking. He’s not a scrappy underdog hero, nor does he really have right on his side: He’s a boy groomed from birth to be the Messiah, even if that grooming is less borne of moral righteousness than the machinations of systems that existed long before he was conceived. Following him through a rollicking space adventure either means ignoring the ugly downfall that’s to come later, or leaning into Paul’s alienness and losing what might make him human and relatable to an audience.

Also, without that nuance, Paul becomes the kind of white savior that critics of Dune have long lambasted; the recent version, with its relative lack of MENA talent on screen and images of ululating throngs of women in burqas reaching out for Paul as their savior, does little to dispel that thought. A solid adaptation of Dune, and of Paul specifically, has to thread those particularly difficult needles. It has to recognize Paul’s thorny nature as a white messiah to a colonized planet, understanding the flawed nature of that savior complex and its short shelf life. At the same time, it has to find a deep core of empathy and humanity for a character who, on paper, is more of a thought exercise in the limitations of prophecy than a swashbuckling action hero.

The limitations of Hollywood filmmaking (and basic-cable budgets) have so far been unable to produce this narrative superbeing. Here’s hoping future turns at bat can turn that around. Otherwise, the real Paul Atreides might just have to live where he always has: in the imaginations of those who read Herbert’s books.

This article was first published on October 21st, 2021, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂