If you’re looking for entry points into the industry, then Mark Siegel is a pretty unorthodox example, but perhaps that’s what makes it so inspiring. His career goes from a slapstick starting point to puppeteering some of 80s cinema’s craziest critters, and then into the emerging field of CGI as a stalwart of Industrial Light and Magic.

Siegel was teaching junior high in his hometown of Minneapolis before turning his back on dispensing education, in favor of receiving it as one of the 1,700 students to pratfall through the doors of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Clown College between 1968 and 1997, earning a spot in their touring show.

There he was fortunate enough to study under the late, great Verne Langdon who “besides teaching us clown makeup and helping develop our characters. He taught us basic prosthetics – he had recently been on the original Planet of the Apes [1968] with John Chambers. I learned how to take the casting of my nose, do sculptures and molds and make my own rubber clown nose. Verne liked my work. And I enjoyed doing it. And we stayed in touch.”

Langdon was a cult figure in horror circles for the range of high-quality Halloween masks he sold through the pages of Famous Monsters of Filmland, and in 1975, he put that know-how to good use and launched Land of a Thousand Faces for the Universal Studio Tour. During the show, which was performed eight times a day, audience members would be pulled on stage and transformed into replicas of Boris Karloff’s bolt-necked Frankenstein’s Monster and Elsa Lanchester’s statuesque Bride of Frankenstein.

“He needed people with the right skills,” explains Siegel on Ed Kramer’s CGI Fridays Episode 1, “[but] couldn’t pay union makeup artists or anything. He knew I had the skills. He wound up hiring me and three other guys he knew from the circus. So I was on the ground floor helping to create and then working for the Land of Thousand Faces for about three and a half years thinking it was a temporary job while I was trying to be an actor. I learned virtually everything about sculpting, mold making, mask making prosthetic makeup effects, a lot of the materials, [and] met some people in the business like Rick Baker because makeup effects were just booming at that time.”

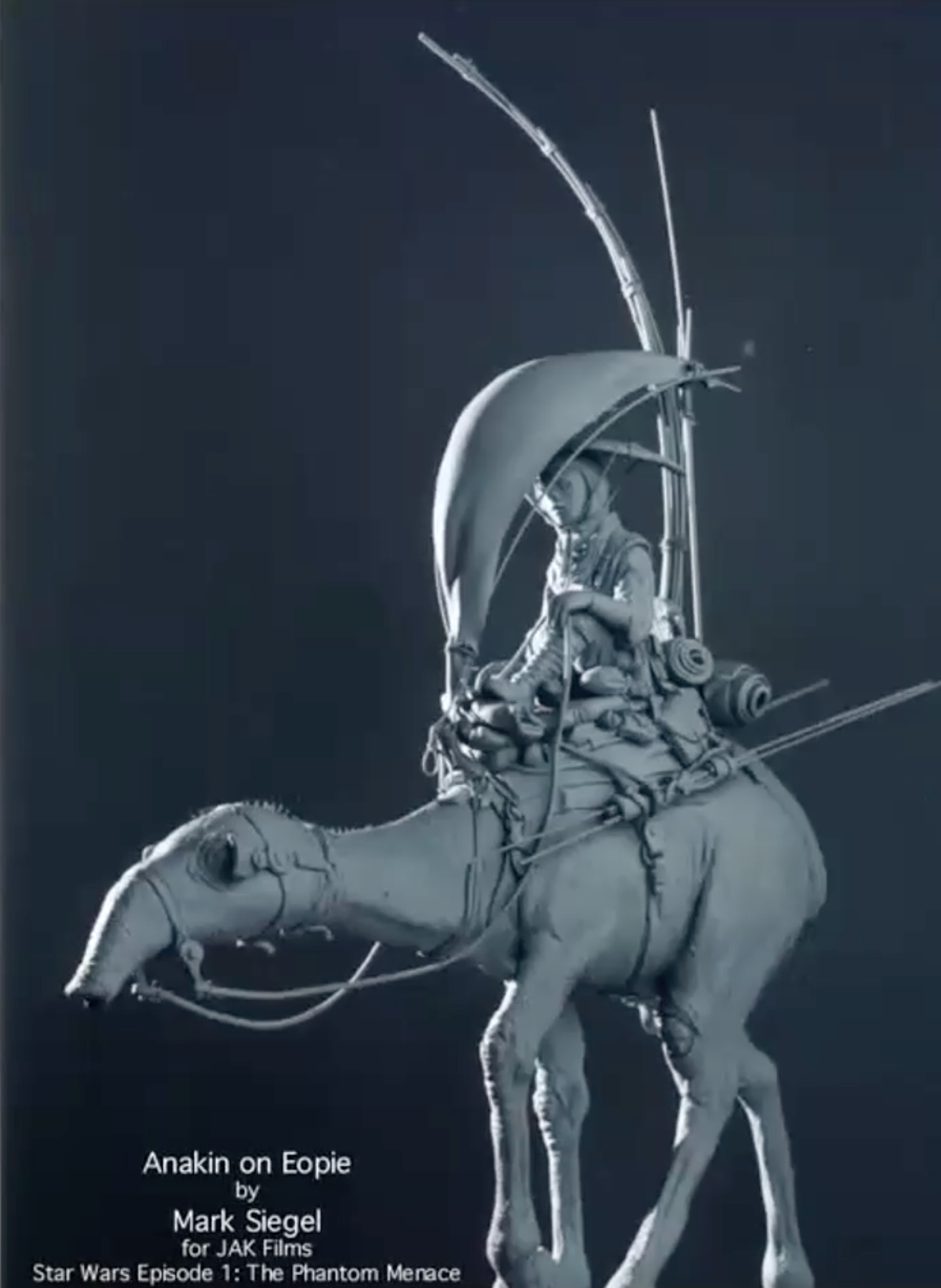

From there, Siegel entered the world of visual effects as a freelancer, racking up an incredible array of credits in the model shops and creature shops for Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi (1983), The Goonies (1985), Big Trouble in Little China (1986), and The Blob (1988).

He sculpted Klingon foreheads for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) and waggled Slimer’s tongue as a puppeteer in Ghostbusters (1984), but while working on John Travolta’s burbling baby comedy Look Who’s Talking (1989) for Magic Vista Studios Inc, Siegel heard that Industrial Light and Magic had been contracted to produce the effects for Ghostbusters II (1989) and put himself forward.

“Slimer was kind of the main reason they hired me and then for a while they were thinking of cutting Slimer out of the movie. And I thought, ‘Oh, maybe I’m out of a job’. Then they brought him back. By that time he had become kind of a star on his own – [he] even had his own cartoon show. So the designs got a little more cartoony. And he’s very cute. But he’s not the original Slimer. And what I loved about the original Slimer was that he really was kind of ugly. He was inspired by John Belushi, especially his character Bluto in Animal House [1978], who was really kind of gross and disgusting and it was just because of his behavior that he was also somehow cute and charming and very funny. That’s a quality that the original Slimer had, and because it went more cartoony, I don’t think that part of it was quite as successful.”

Siegel did, however, get an opportunity to correct the record as he saw it when the Planet Hollywood chain of themed restaurants commissioned a sculpture from ILM.

“I thought, ‘Okay, this is the opportunity, I have to bring it back a little bit closer to the original Slimer without departing too much from the one we were working on. Because I mean, that’s what we’re working on. It couldn’t do that. But I brought back the body proportions, quite a bit more. I kept the smile, but it was not quite as broad and extreme. His cheeks are not quite as wide.”

Siegel’s journey from the model shop to CGI was a gradual one, but one he credits with an early interest in the potential of computer graphics and with ILM’s determination to invest in its existing team. CGI was still a new field and the model shop was often tasked with producing physical prototypes so that the animators could study them. Bizarrely, that means some of Siegel’s VFX credits from the era aren’t actually visible on the screen – these include a shark glove puppet for test shots in Back to the Future Part III (1989) and a sculpt of the metallic T-1000 for Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991) so that they could examine the way the light plays on the liquid metal fabric of Robert Patrick’s uniform.

“Then, of course, Jurassic Park [1993] happened and I was blown away by it because all of us from the model shop got called into the little D screening room and got to see some of the test footage. A lot of the people were saying, ‘Well, there goes my job’. But I was thinking ‘This is really cool.’ Eventually, ILM started making self-training available to those of us in the model shop. To ILM’s credit, they recognized that the art is the art and the artist is the artist. And if you could learn another tool, you bring the same eye and the same creative skills to that tool. They were encouraging people with the practical skills to start moving over to CG. It was frustrating because we didn’t have official training, they just made computers and some manuals and software available to us to do after hours, after a regular day of work.”

This is just a snapshot of Mark Siegel’s incredible conversation with Ed Kramer, so if you want to hear a pair of CGI wizards geek out over Ghostbusters and Star Wars, or trade stories from their time on Galaxy Quest, and Pirates of the Caribbean then you can listen to Ed Kramer’s CGI Fridays episode 1 above, or through your podcast platform of choice.

This article was first published on June 3rd, 2022, on the original Companion website.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂