The evening before we’re due to speak, Cameron M. Smith – archaeologist of early humanity, explorer of Earth’s frozen extremities, homebrew spacesuit engineer, and professor of Anthropology at Portland State University – emails over a quote from the late physicist and mathematician Freemon J. Dyson’s From Eros to Gaia (1992):

“Space is huge enough so that somewhere in its vastness there will always be a place for rebels and outlaws. Near to the sun, space will belong to big governments and computerized industries. Outside, the open frontier will beckon as it has beckoned before, to persecuted minorities escaping from oppression, to religious fanatics escaping from their neighbors, to recalcitrant teenagers escaping from their parents, to lovers of solitude escaping from crowds. Perhaps most important of all for man’s future, there will be groups of people setting out to find a place where they can be free from prying eyes…”

The author of Principles of Space Anthropology: Establishing a Science of Human Space Settlement and Emigrating Beyond Earth Human Adaptation and Space Colonization is reflecting on The Expanse shortly after the conclusion of Season 6. In particular, the extent to which shifts in language and culture, depicted on screen and in the books by James S.A. Corey track perfectly with the current thinking of anthropologists.

“What’s so compelling is that it’s so plausible,” he says. “They go to space and it doesn’t fix all of humanity’s problems. We carry those problems with us. And they have conflict and I think that’s going to be the case. I don’t think [space settlement is] the ultimate solution for our problems. But I think going beyond our planet, at least offers opportunities for new ways of thinking, and new philosophies.

“[Robert] Heinlein said, when it gets so crowded that you have to carry an ID, it’s time to move. I like this concept.”

Space Incorporated: Scratch SpaceX, Get Protogen?

“A hundred and fifty years before, when the parochial disagreements between Earth and Mars had been on the verge of war, the Belt had been a far horizon of tremendous mineral wealth beyond viable economic reach, and the outer planets had been beyond even the most unrealistic corporate dream.”

So opens Leviathan Wakes (2011) by James S.A. Corey, the first book in the series. The idea of big business wielding all-but-unchecked power over the lives of settlers and spacefarers has been a concern of science fiction long before Nostromo’s sealed subroutines. The exploitation of Belters by Inners (inhabitants of Earth and Mars) that underpins grievances in The Expanse aren’t new themes for science fiction to explore, but they are more relevant than ever.

Warnings about unregulated corporate adventures beyond Earth’s atmosphere grew in intensity when in May 2020, SpaceX became the first private company to put a crewed flight into orbit. Born out of billionaire shitposter Elon Musk’s long-held ambition to plant mankind on Mars, he was beaten to the 66-mile high club by Amazon tycoon Jeff Bezos, who led Blue Origin’s first crewed flight in July 2021 personally and then went back in October with the 90-year-old William Shatner. Presumably, the insurance premiums were eyewatering.

The last launch operated directly by NASA and not contracted to a commercial operator was in 2011. For over a decade, hopes in the west for space exploration and settlement rested on the private sector. Fellow space anthropologist Savannah Mandel has described the risks in strident terms, telling Frankie magazine in 2021: “Whoever owns those space settlements gets to make the rules. If Jeff Bezos puts a colony on Mars, Amazon will control it.”

“Suppose everyone has access to resources on the Moon,” she continued. “That’s great in theory. But the people who actually get there and mine it in the first place, they’re going to be the super-wealthy or heads of government, or people working for them, so the wealthy will just get wealthier. And if someone breaks a Moon Treaty up there [or] if someone wants to explode a nuke on the Moon, who’s going to stop them?”

“Even 10 years ago it was a much more, maybe naive,” Cameron reflects, “I just kind of thought, well, we’ll go to space and open up these new states for human thought and philosophy and art and all of that. I still think that will happen.

“But then there is, of course, human conflict. One of the most compelling things to me about The Expanse is the brutality of that space environment, and how easily it’s manipulated to control people. The Belters are running on hope. For them, it’s very tough, because they depend on others for all resources. Their thing is to try to get independent of that.

“On Earth, it’s rampant. And it seems unstoppable. You can boycott Coca-Cola or whatever, but it doesn’t seem to make much of a difference. I think [space settlement is] still a good idea. I think we still should, you know? It’s at least it’s a chance, it’s a chance for new concepts. And I think of the Renaissance: it came from new discoveries, they used telescopes, they use microscopes. They’re finding we’re not the center of the universe. Along comes evolutionary conceptions: ‘Aha, there’s a mechanism behind everything that is alive, it’s not necessarily just popped up out of nowhere from the mind of a great Creator’. So all those things are happening. And the new philosophy of humanity emerges right during the Renaissance.

“I think that the potential is there for the same thing with going into space. But now that I look at The Expanse, I think about it a little bit more realistically, perhaps maybe not quite as optimistically, or maybe not quite as naively.”

Resource Management: “Our Air, Our Water”

Even without the murderous machinations of Protogen and its parent company, Mao-Kwikowski Mercantile making Weyland-Yutani look like Lush, corporate control over vital resources – air, water, food – is potentially problematic. It seems inevitable that where a resource is scarce, that resource will command a premium. Even with a hypothetical state intervention to deliver this fundamental precondition for life as a human right, someone will have to control it and somebody will have to pay for it.

The very first episode of The Expanse, ‘Dulcinea’ (S1, Ep1), takes us inside the politics of Ceres Station. One of the earliest settlements in the Belt and the de-facto capital of its separatist aspirations, Tycho Manufacturing and Engineering Concern hollowed out the asteroid in search of every last scintilla of mineral wealth and span it into gravitational life to use as a supply hub. Although a UN protectorate at the beginning of the series, Earth is an absentee landlord. The private sector is responsible for law enforcement (Star Helix Security), whilst the flow of water (courtesy of ice trawlers like those of Pur’n’Kleen) is turned on and off at whim or siphoned away by black marketeers and criminal cartels. Water rationing is so severe that windows are caked in grime.

The episode’s Belter firebrand tells us:

“This station became the most vital port in the Belt. But the immense wealth and resources that flow through our gates were never meant for us. Belters work the docks, loading and unloading precious cargo. We fix the pipes and filters that keep this rock living and breathing. We Belters toil and suffer, without hope and without end – and for what? […] Every time we demand to be heard, they hold back our water – owkwa beltalowda – ration our air – ereluf beltalowda – until we crawl back into our holes – imbobo beltalowda – and do as we are told!

Savannah Mandel’s predictions about conflict between corporations and individuals play out with the opening of the ring gate in The Expanse Season 4. In this feeding frenzy for the furthest reaches of known space, Royal Charter Energy and their trigger-happy corporate enforcers provide the friction. Under shark-eyed security chief Murtry (Burn Gorman), they’re willing to defend their corporate claim to gloomy Ilus IV even if it means the deaths of innocents – Belter refugees from Ganymede whose settlement predates their arrival by two years and the grant of their ‘exclusive charter’ by three months.

Murtry holds no illusions, telling holden in ‘Saeculum’ (S4, Ep9):

Murtry: People like you always forget, civilization has a lag time. Like light delay. You come out here, and you think because you’re civilized, civilization comes with you.

Holden: Throw your gun down, and put your hands on your head. We’ll only get this one chance.

Murtry: You’re just walking in the footsteps of history. The ancient frontier. Those post offices, and railroads, and jails, cost thousands of lives to build. This is no different. I am the kind of man the frontier needs. You’re the kind that comes after my work is done. You should have stayed at home…’til I built a post office.

“If you have a resource that people want,” says Cameron, “then somebody is going to grab control of that resource. That’s not just a Western industrialization thing. Here on the northwest coast of North America, there were resources in pre-European times like salmon. They go up a river at a certain time of year, and everybody wants them. In certain places, native people built villages right at the spot where that run was happening. They, therefore, controlled that resource. If you wanted to come and fish, they’re like ‘Great, you can fish’, but they’re going to take 10 percent of whatever you got. So they quickly apprehended that, okay, we can basically control this resource.

“Its very cool term is ‘the deviation amplification model’. So the deviation is that at some point during the year, there’s not much salmon, then the deviation is that there’s a lot of salmon, but if you move there and you control who gets access to the salmon, you are a deviation amplifier. We have great documents like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that we came up with after World War II that tried to ensure access to resources for all, but we also have a long history of the deviation amplification or control of access to resources.”

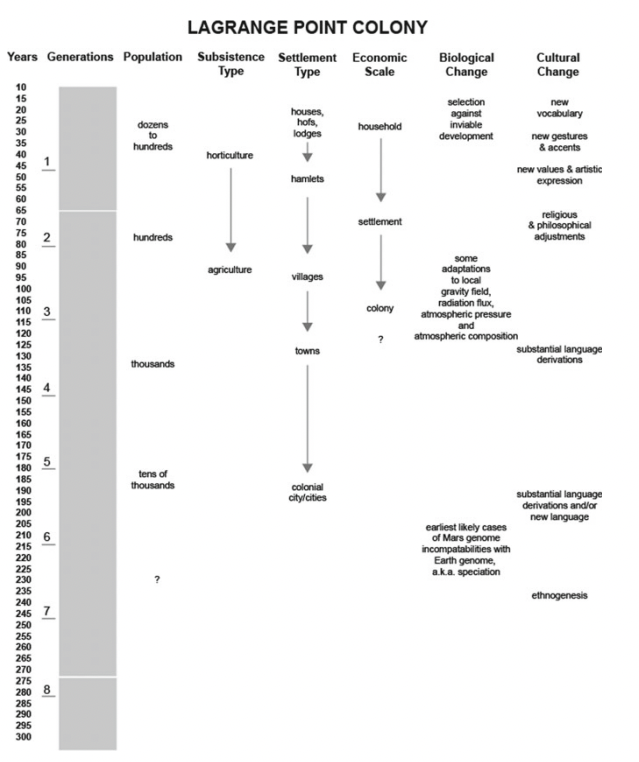

Lang Belta: Words Have Power

In Principles of Space Anthropology (2019), Cameron presents a timeline for how a colony on Mars and at Lagrange Point 5 (a space station in a stable orbit) might develop, in terms of population, economic, cultural, and even biological change. Within 20 years of a colony being settled, you might see new vocabulary; within 30-40 you see new gestures and accents; and by the third or fourth generation, you begin to see substantial changes to language that give way to new dialects or even entirely new languages by the fifth or sixth generation.

Lang belta, the creole of the Belt is more pronounced in the novels but was tooled for the show by linguists to be both intelligible for a TV audience and believable as a creole.

“If you’re only speaking English, you can maybe make out a couple of things,” says Cameron. “But this is a timescale of several centuries. If we look at our own experience on Earth, it’s a few centuries from Shakespearean English to our English. You can kind of get the gist of it, but to really study it you take classes. So I think that the timescale and the amount of divergence [of lang belta] is very realistic. There’s ethnogenesis: new cultures arising, new values, new languages, new food, all these ways that we distinguish our cultures from one another. That also occurs on that sort of timescale.

“You need a couple of generations to teach new values. It’s very hard to change adult values, so you wait till the next generation comes along, and you try and instill it in them. Then okay, they get it and but then there’s always the tension between the teenagers and the adults, so you have to keep drumming it in for a couple of generations. In the case of the Belters, one way to do that is to amplify the difference between Earth’s language and their language. You can use that as a tool to further your greater philosophy, which is distance or separation from Earth by not just patois or pidgin language, but now let’s really push it and diverge our language even further.”

It’s interesting in retrospect to watch how key figures within the OPA – the Outer Planets Alliance – use language. Anderson Dawes (Jared Harris) seems to almost revel in the juxtaposition between his power and sophistication and the language of the underclass, taking on a poetic edge, almost seductive as he urges restraint or rebellion to suit. Camina Drummer (Cara Gee) – who modeled her accent on Dawes giving the character the same hard vowels found in Multicultural London English – perpetually bristles, hiding behind its sullen syllables until destiny comes calling. In her powerful speech to the crew of repurposed Mormon generation ship OPA Behemoth in The Expanse episode ‘Intransigence’ (S3, Ep9), the words roll from her mouth with growing momentum. The cadence is of the Belt, but she uses surprisingly few words of lang belta, as if the trappings of authority remain in the orthodoxy of Earth and Mars:

“This is your ship. This is your moment. You may think that you are scared. But you are not. That is your sharpness. That’s your power. We are Belters. Nothing in the world is foreign to us. The place we go is the place we belong. This is no different. No one has more right to this. None more prepared. Inyalowda go through the ring. Call it there own. But a Belter opened it. We are The Belt. We are strong. We are sharp and we don’t feel fear. This moment belongs to us. For Beltalowada!”

Klaes Ashford (David Staithern), her political rival and expected usurper, throws his weight behind her, bringing his palm down heavily on a handrail. The rest of the crew follow with a round of applause or signal of affirmation suited to a people born in space: we’re coming with you.

“They use the language not just for communication, but it’s used politically,” Cameron continues. “It’s used socially, to make a point. The detective, Miller, I started out hating him, but I really loved him at the end and now that I’m watching it, I’m realizing, oh, wait a minute, he was a Belter. Then he kind of defected and became an opportunist or whatever. He’s able to speak that language, but he doesn’t always speak it. He’s using it politically. He’s using it socially. There’s a lot more to [language] than just moving information around.”

This Land is Our Land: Martian Idealism

The evolution of a distinct culture is often one of the tipping points toward independence. Economically too, the scale shows us that within two generations, the settlement is considered a settlement, within two to three generations a colony, and beyond that point is a question mark. Although it looks at economic systems, rather than the yearning for self-determination, both settlement and colony imply a strictly subordinate relationship with a distant Earth. Whilst a settlement is dependent upon material support from the homeworld, a colony is more self-sufficient. In that instance, the ‘?’ represents the unknown, the uncertainty, the rising grumbles at inequality, and the burning desire for the hands that mine the ore or service the systems to receive the rewards.

Or as Ceres Station’s OPA kingpin Anderson Dawes puts it in The Expanse episode ‘Back to the Butcher’ (S1, Ep5):

“Earthers get to walk outside into the light, breathe pure air, look up at a blue sky, and see something that gives them hope. And what do they do? They look past that light, past that blue sky. They see the stars, and they think, ‘Mine.’”

It’s striking how the timeline in Principles of Space Anthropology matches up almost perfectly with what we know about mankind’s settlement on Mars and then violent break with the UN in The Expanse, and where the Belt now finds itself at the start of the series. Both Mars then and the Belt now sit firmly in Cameron’s economic ‘?.’

Even knowing the level of research the writers have invested into their universe – both on the page and on the screen – it shouldn’t be surprising in the slightest that their vision of the future aligns with the anthropological models, but somehow it still is. Nothing in The Expanse is throwaway, it’s considered.

“We’ve been watching the first season again,” Cameron says. “I’m struck by it with Mars, they’re very idealistic. Basically, they say – and I guess the Belters are kind of the same – you take Earth for granted. You don’t know what you have and that’s why we hate you so much. Because you are just abusing this thing that is so precious. Look at us, we’re on a rock, and we have to invent everything. And we have to make everything ourselves. You’ve got oxygen and water. And food is just growing on the surface of your planet.”

Lopez (Greg Bryk), the Martian intelligence officer who interrogates the survivors of the Cant, tells Holden (Steven Strait) the same in the harrowing Expanse episode ‘CQB’ (S1, Ep4):

“My great uncle emigrated from Earth. He missed it terribly. He used to tell me stories when I was a little boy about these…endless blue skies, free air everywhere, open water all the way to the horizon. He told me that someday we would make Mars just like that. When you spend your whole life living under a dome, even the idea of an ocean seems impossible to imagine. I could never understand your people. Why, when the universe has bestowed so much upon you, do you seem to care so little for it?”

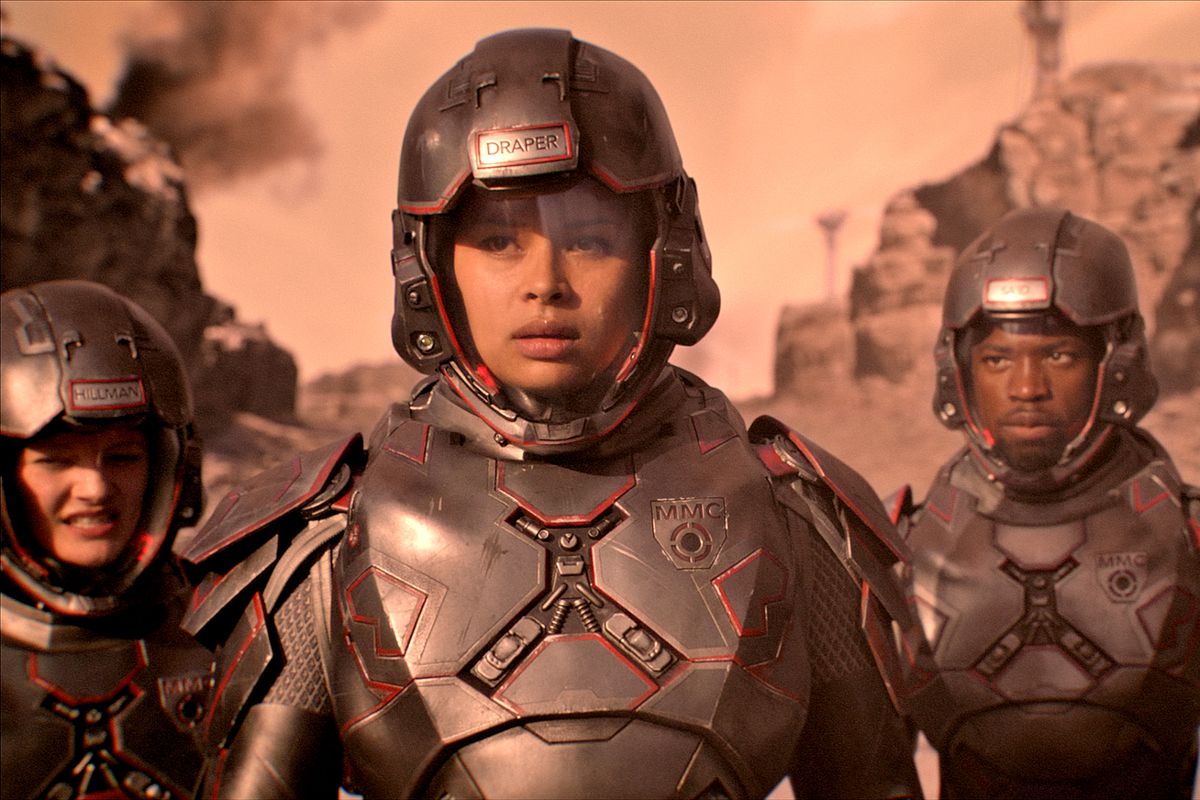

Whilst the Martian Congressional Republic has a few generations of settlement over the Belt, its culture is nowhere near as wild a departure from Earth’s. This isn’t evidence of the series’ meticulous worldbuilding finally coming up short – the opposite. The proximity to Earth has ensured a more predictable pattern of immigration and ideas, whilst a cohesive state – a single navy and government – relies on uniformity of language and values to function, especially so given. the highly militarized character of Martian culture.

“It’s a shorter travel time to Earth,” Cameron explains. “So Earth concepts are just more portable. They’re easily more easily maintained on Mars but Ceres where the Belters are, the asteroid belt [is] a little bit further. There’s more scope there for more radical ideas.”

Mars may be closer to Earth, but it’s still far enough for independence to flower, unlike Luna which remains an appendage of the UN.

“Jeez, who said it? It was a Robert Zubrin of the Mars Society. He had kind of the same idea. People said, ‘Let’s build a new colony on the Moon’. And he says, ‘No, that’s too close’. If you really want a Renaissance, you have to go further away. So it’s harder to get there. So he was talking about Mars. The quotation I remember from him about this is he said ‘Anywhere, but Mars, the cops are too close.’

“Earth is always going to be in control of the Moon because they’re so close – they can control it. But if you go to Mars, you need to have a philosophy of independence, because it’s too dangerous to say, ‘Well, we have to depend on Earth’. So on Mars, there’s a distance that is great enough to start to foster real independence.”

Born out of this philosophy of independence (or fear the cops were too close) is a shared vision common to settler communities that grow towards statehood, to build a paradise in the dust. Reality and mythology may not always line up – particularly if the land is already inhabited – but the transforming zeal shaped the first centuries of settlement in Canada, the United States, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

“If you’re a farmer,” says Cameron, “and you’re on a plot of land, and you’ve put all your blood and sweat and tears into that one plot and you’re less well, you can’t just pick up and leave it. You’ve literally got people buried under the house – early farming communities buried their people inside their houses, under the floors. So they’re heavily invested with a spot on the landscape.”

On Mars too there is a relationship with the land, a fixed point that Belters lack. The Earth’s ambassador to Mars Franklin Degraaf sums it up best in ‘Remember the Cant’ (S1, Ep3):

“You know what I love most about Mars? They still dream. We gave up. They’re an entire culture dedicated to a common goal, working together as one to turn a lifeless rock into a garden. We had a garden and we paved it.”

We Go Together: Beratna Collectivism

It’s probably doing the source material a disservice to distill it into binaries, but Mars and the Belt present two very distinct directions of travel. Mars is a seemingly unified and homogenous whole, driven by a single purpose to reshape an inhospitable environment, whilst the Belt is as disparate as the asteroids themselves, boasting as many factions as there are crews.

For Martians, there is Mars.

For Belters, there is the ship or station first, and the ill-defined collective identity of ‘the Belt’ second. For all their disdain for welwala deemed too close to the inyalowda, the six seasons of The Expanse have shown us Belters repeated break with their faction or consort with Inners (for the good of the Belt), but only when they break the trust of their comrades – as Naomi (Dominque Tipper) does with Marco Inaros and her estranged son, Filip (Jasai Chase-Owens) – do they go beyond the pale.

Family and crew are literally interchangeable, not just with Naomi in her earlier life on Pallas Station, but with Drummer’s polyamorous found family aboard Dewalt and Mowteng. Decisions aboard Dewalt and Mowteng were made collectively in consultation with the crew; they ate together, fought together, and slept together. Even as the family splintered, changed, and grew, it remained Drummer’s family. This contrasts sharply with Naomi.

After her betrayal of Roci by leaking the Protomolecule to Fred Johnson (Chad Coleman), her abandonment of Drummer, and then her second escape from Inaros, Naomi is finally cast adrift. She cuts a lonely figure in Season 6. Having lost the confidence of all but the unflinchingly devoted Holden, she finds herself a member of the lowest single unit in Belter society: a Belter without Beratnas.

Writing in the space journal Room, Dr. Elizabeth Tiarks – Senior Lecturer at Northumbria University Law School – suggested restorative justice, particularly the empowerment-focused conferencing model, as a means of conflict resolution in space missions where access to more formal solutions is impossible. This process involves the entire crew – offender included – discussing the situation and agreeing on the solutions (or punishment) as a means of cauterizing the disruption and returning everyone to their duties.

“I was just listening to an audiobook of James Cook, the explorer,” Cameron continues. “You listen to his diaries, and it’s very interesting. He doesn’t talk about the crew, he talks about the people. I swear, his number one concern is making sure that they’re well-fed and warm. It’s a tough life, they have to do these jobs, and they can get bad punishments if they do them wrong, but it’s like a family. He’s the big man of the family, but it’s like a family. That’s because they’re on the edge. They have to stick together. They have to stay together. Because if anyone screws up, everyone could suffer.

“That’s very much like the crews of these ships or the Belters. My favorite character in The Expanse may be Anderson Dawes. Everything with him is very grey, but he does have a guiding compass, which is to keep the Belters alive, [and] keep them going. It’s like that James Cook ship where there’s a very clear guiding principle, which is independence for those people, and brutal things can result from that if they really desperately committed to that.

“Getting your people over the horizon, you can achieve that in different ways. You can achieve it through tyranny, but you can also achieve it through a more communal effort. This is the fine line or the tightrope that we’re always walking with human cultures; how much power do we give to our leaders? Do we have leaders? Or do we have rulers? There’s a great book called From Leaders to Rulers. It’s about this whole question: how has humanity in the past achieved its goals? How did humanity go from having leaders to having rulers? How do people give up their independence? Which they seem to have in smaller, more mobile cultures, like hunting and gathering, they have leaders, but not rulers.

“Agriculturalists almost always end up having rulers. Maybe it’s deviation amplification, rulers managed to get hold of basic things.”

Oxygen, for instance, or the Protomolecule.

Cameron M. Smith still thinks humanity’s future is in the stars. He wouldn’t have scratch-built his own thousand-dollar pressure suit or tested his endurance for some of the harshest environments on Earth if he planned to stick around, but he’s much less optimistic about how we’re going to behave once we get there.

Or as Miller would say:

“Optimism is for assholes and Earthers.”

And he does have something of the Belt about him, don’t you think?

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂