"I am Tank Girl." This is what Lori Petty thought to herself after she read the script for what would become the 1995 feminist sci-fi cult film Tank Girl. Twenty-five years later, this is one of the first things she tells me over the phone.

At this point, Petty was a star-in-the-making. She’d been acting in TV since the mid-80s and had had key roles in some of the 1990s’ most beloved films, most notably in Point Break (1991), as the orphaned surfer girl Tyler Endicott (who teaches Keanu Reeves’ Johnny Utah how to surf) and A League of Their Own (1992), as the headstrong pitcher Kit Keller.

Petty’s easy-going, natural good looks, athleticism and charm shone through in all these roles. She was never the cute, quiet girl next door. In the roles she played leading up to Tank Girl, there was always a certain sass-filled charm that shone through. She could kiss you, or punch you in the face, you never knew which was coming. Which is exactly the type of unpredictable, wild charisma that made her perfect for Tank Girl.

For anyone who’s not seen Tank Girl, let me try and describe it and entice you to continue reading and, perhaps, seek this bizarro riot grrl gem out.

The film is set in 2033, in a post-apocalyptic world where water is a rare commodity. Rebecca ‘Tank Girl’ Buck is a quippy, dirty-talking punk that lives in the Australian outback and generally minds her own business…until she gets captured by the evil corporation that controls the world’s remaining water supply, Water & Power (W&P). They kill her boyfriend, torture her and are generally evil. But she runs away, finds a tank and falls in love with a kangaroo-man hybrid.

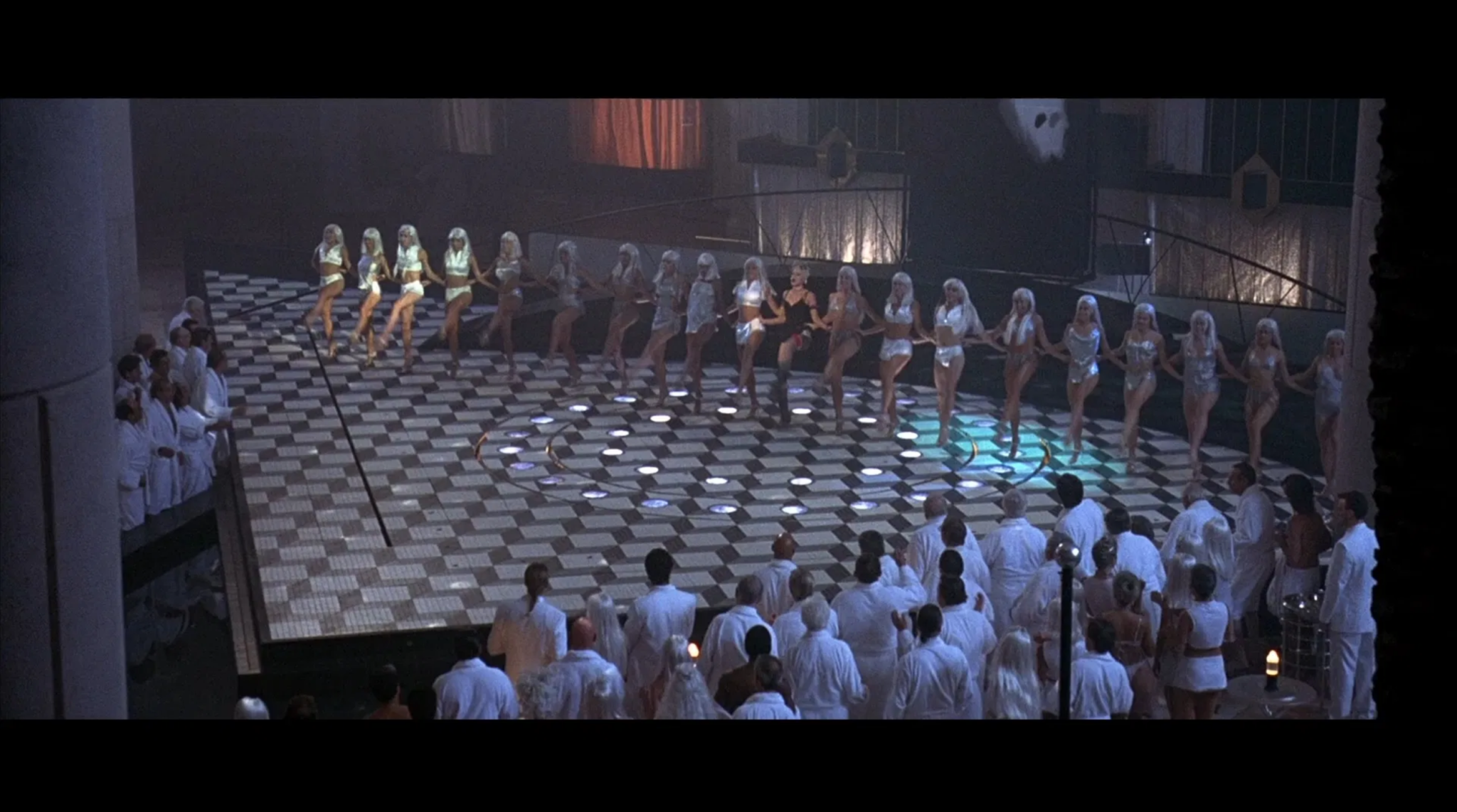

The plot is nonsensical. The fashion is outrageous. The dialogue is frisky. The horniness is out of control. There are kangaroo-soldier hybrid creatures. And a Busby Berkeley-style musical rendition of Cole Porter’s Let’s Do It. Plus a cyberpunk makeover montage. It’s a film that also stars Naomi Watts, Malcolm McDowell, Ice-T and Iggy Pop.

Put simply, Tank Girl is pure anarchy on screen. It’s off-putting, berserker randomness in its purest form. And it’s glorious.

The film, which is most often referenced in articles about box office flops or makes its way onto the weirdest-films-ever-made lists, turns twenty-five this year. Even now, it sizzles with energy. It’s offbeat, and by no means perfect, but anchored by Petty’s performance. There is a radical kindness that shines through her take on Tank Girl. In a point in time where kindness is the word du jour, it’s interesting to look back at a protagonist that remains a wild, unapologetic, hilarious, and entirely indomitable heroine. There’s nothing quite like Tank Girl, before or since.

The Hero We Need: "I'm not bedtime story lady"

The first thing we hear from Tank Girl sets the scene for the film: “Listen up, cause I’m only telling you this once. I’m not bedtime story lady, so pay attention.”

She definitely isn’t.

Based on the comic book series created by Alan Martin and Jamie Hewlett and originally published in the debut issue of Deadline magazine in 1988, Tank Girl was designed to be in-your-face.

Her real name is Rebecca Buck, but that will rarely come up. On the page, she swears, drinks, farts, fucks, spits, and is prone to violence, and shit-talking. In a 2007 interview, Hewlett described the character:

"We’d just see how far we could go before somebody said ‘stop, you’re not allowed to do that’. And nobody ever did, so we just pushed it further and further." - Jamie Hewlett.

She was the opposite of everything considered ladylike. Set in a post-apocalyptic Australian outback, the comic drew heavily from British pop culture and quickly became an icon of counterculture. Tank Girl became a punk and a queer poster girl: her image showed up on merch and on protest signs against Clause 28 (Margaret Thatcher’s amendment that limited British local authorities from ‘promoting homosexuality’). There were weekly lesbian nights in London dubbed ‘Tank Girl nights’. The popularity and success of the comic strip eventually made its way to Hollywood. Deadline’s publisher, Tom Astor, began shopping the comic around studios just a year after its original publication.

At the same time, filmmaker Rachel Talalay discovered the comic book whilst making her directorial debut with Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare (1991), the fifth instalment in the Nightmare on Elm Street franchise.

Talalay had been working in film for a decade at this point, working her way up in production roles and fell in love with the character. She wanted to make the Tank Girl film and got in touch with Astor. After hearing nothing back for almost a year (rumour is that she was low down the totem pole of potential directors), she finally secured the rights and pitched the idea to Steven Spielberg’s production company Amblin Entertainment and Columbia Pictures. Both passed. However, MGM came on board and Tank Girl began assembling the team, with Talalay at the helm and working closely with the comic’s creators, Hewlett and Martin. Jamie Hewlett said: “Can you imagine a 23-year-old being flown to Hollywood and picked up in limos?” he laughs. “I mean, they lay all that shit on.”

Although it might seem like a little punk rock movie, there was a stunning amount of talent involved with the production, both established and newcomers. The great Stan Winston, the make-up effects designer who’d already picked up three Academy Awards for his work on Aliens (1986), Terminator: Judgement Day (1991) and Jurassic Park (1993), worked on the creature effects. Courtney Love, then the frontwoman of punk band Hole, recently widowed and with her second album Live Through This garnering critical acclaim, curated the soundtrack. The costume designer Arianne Phillips had just made The Crow (1994) and would go on to be a triple-Oscar nominee for her work on Walk the Line (2006), W.E. (2012) and Once Upon a Time in… Hollywood (2020). The production designer was Catherine Hardwicke, who’d already worked on films like Braindead (1990) and Tombstone (1993) and would go on to become a director herself, making Thirteen (2003), Lords of Dogtown (2005) and Twilight (2008).

Tank Girl was a relatively big-budget action film, with a kitty of $25 million and studio backing. The production made the casting of the lead role into a publicity stunt, advertising that they were looking for “a stunning woman in her twenties, spirited, sexy, quick-witted, irreverent and tough, possessing a rugged rock & roll spirit! Able to take care of herself in most situations, both physically and mentally; and rides a water buffalo. (No go-go boots; no white shoes!).”

Enter Lori Petty. The actress had just released Point Break (1991) and A League of Their Own (1992), and was on the cusp of breaking into leading roles. She was not familiar with the Tank Girl comic books, but once she read the script, the role became an obsession. “I am Tank Girl,” she said to herself, to her agents, to everyone around her. Petty wanted the role, badly. She devoured all the comic books and was ready to go. She was told she had to audition (“Yeah, yeah, sure, but I am Tank Girl”). When the casting of English actress Emily Lloyd (A River Runs Through It) was announced, on the front page of The Hollywood Reporter, she was on the set of In the Army Now (1994), filming with Pauly Shore, Andy Dick and David Alan Grier. She wanted the role so bad, her trailer was covered in Tank Girl comics, pasted onto the walls. The actors came into her trailer to break the news to her, showing her the headline and offering their condolences. She didn’t believe them. They started gently taking down the torn out pages of the comic books but she was incredulous: “What are you talking about,” she reminisced, “I’m Tank Girl.”

Some weeks later, the actress that had been cast was let go because she refused to cut her hair for the role and Petty got the call.

It’s impossible to imagine any other performer giving so much to this role. The film lives and breathes through Petty’s performance. Her physical performance is almost slapstick-like. Her movements are jittery, when she runs she or fights it’s like she’s never run before in her life, but no one has told her. “She doesn’t come from reality, she comes from a comic book, from the page,” she says, “So she couldn’t be human.” She shifts from dirty jokes to tender teasing in the blink of an eye. Every situation is turned into a joke. Petty maintains the same intensity throughout the whole film as if Tank Girl herself had jumped out of the page momentarily to poke fun at the mere idea of a movie version of herself.

Tank Girl is the very definition of in-your-face. Nothing about her is chill or quotidien. She is the sort of girl you’d see in the skate park in your hometown, falling on her ass with a laugh, with consistently scraped knees, a different hair colour every week. Always fierce, fearless and completely magnetic.

Much of the dialogue was improvised by Petty. Her favourite line she said she took from her Black queer friends and the underground ballroom scene: “Darling, you are so pretty it makes me sick.” A lot of the improvisation on set was her, just talking. One time, she winked at the classic line “I’m too old for this shit!” and Talalay exclaimed: “Never say that! Tank Girl doesn’t age!”

Tank Girl is our conduit into this world. There isn’t much world-building of this post-apocalyptic world, we don’t really spend time on understanding what happened, or learning anything about this reality. It doesn’t really matter, it just is. She’s talking directly to us from the very first moment of the film and almost everything about the film is experienced from her point of view.

She introduces us to her community: her boyfriend Richard, a hunk of a man we get to know only briefly and mostly naked; and Sam, a young girl who’s fascinated with the Rippers (feared creatures no one has seen). “She’s got a community. She cares about them,” said Petty, “She doesn’t have any power, she just wants some water.” Tank Girl’s relationship with Sam is tender and sisterly. She teaches her how to be a proper young lady (“Don’t say buttsmear. It’s not becoming. Say… asshole. Or dickwad.”), gifts her snazzy weapons and protects her. The production design of their shared house is nothing short of North London warehouse communal living goals, complete with an underground greenhouse.

Her community is defined only by their opposition to W&P. W&P is a ridiculous caricature of an evil corporation, led by the masterfully evil Kesslee, played with delicious glee by Malcolm McDowell.

Horny on Main: "It's... really... hard for me... to play with myself in this thing."

What still resonates, perhaps now more than ever, is Tank Girl’s overt, playful sexuality. She forces her boyfriend to strip for her, role-playing a spy. She cuts up her pantyhose with a pair of neon pink and green toy scissors, the camera lingering over her legs. She taunts the W&P henchmen with dick jokes.

Tank Girl’s sexuality is very much in the comic book. Hewlett has said that the character is loosely based on “a group of girls I used to go to college with who were unruly and sexy, and kind of bad, which inspired me.”

The film’s Tank Girl is sexual and sexy, but the polar opposite of performative sexiness. Everything is on her terms. Petty shifts effortlessly between manic energy and intense horniness in seconds. Trapped in a truck with a handful of leering henchmen and a single streak of blood flowing down her face, she barks: “I like pain. Hot oil. Vacuum attachments.”

She plays around with the way men look at her, throwing their lascivious gaze back at them before, say, blowing them up with their own grenade or snapping their neck with her legs. It’s glorious to watch her be completely in control of her own sexuality whilst being entirely aware of the way that the men in the film look at her and other women. Tank Girl is undaunted by their advances, but that doesn’t mean she’s oblivious. She’s spikey, but there’s no hardness to her character.

When a guy sexually harasses Jet (Naomi Watts, in one of her very first roles) in return for his protection, Tank Girl interferes and protects her, taking the shy engineer under her wing.

"The moment I feel teeth. You feel lead."

When a paedophile patron (played by Iggy Pop, because why not?) of the cyberpunk brothel Liquid Silver demands an underage girl, Tank Girl humiliates the madam of the place by making her sing Let’s Do It. Which evolves into a Busby Berkeley-inspired peak chaotic musical interlude that includes Tank Girl dry-humping some henchmen while singing Cole Porter.

It’s understandable that Tank Girl is a divisive property, because it cares so very little about its plot, and has no interest in a grand overarching narrative, or setting up a big franchise. Sex is one of the biggest themes of Tank Girl, as is the constant threat of sexual violence against women. She saves Jet. She saves Sam. She interferes when she sees a woman or girl being harassed. But she refuses to be afraid. In one scene with Jet, now her perennially terrified sidekick, she just rolls her eyes and says: “Jet, they’re men.” The men in the film are caricatures of what we now call ‘toxic masculinity’. “Sometimes the guys are threatened by it – the older agents,” said Talalay in a 1994 interview. “Like, ‘What is this? Why are the only good guys in the script mutant kangaroos?’” Sex is arguably the one thing that Tank Girl takes seriously whilst also making it a key part of its humour. Tank Girl will shift anything into a dirty joke.

One of the most notorious aspects of the film were the Rippers, the man-kangaroo hybrids that became allies to Tank Girl and Jet, and our leading lady’s romance with Booga (Jeff Kober). Talalay knew the interspecies romance would probably be a bit much for the studio, so the subplot was only worked into the script after several drafts were handed in. And yet, a love scene between Booga and Tank Girl got cut from the final version. “Tell you what, though,” Petty confides, “I have a photo of Booga naked. With a humongous, fabulous penis. Anatomically correct.” Reader, I squealed when she told me this. It’s the most Tank Girl thing that could’ve happened during an interview with Lori Petty.

"How come you always cover up your mouth when you smile?"

The production of Tank Girl was infamously problematic. The studio, initially intent on making a quirky, punky action film, quickly took away creative freedom from Talalay and the battles for control of the film became an everyday ordeal.

Filming lasted 16 weeks, and mid-shoot Talalay also found out she was pregnant. The production was gruelling: “If I worked 16 hour days, they worked 20 hour days,” said Petty about the crew, “I’d wake up, work out, go to work, makeup, shoot, go back home, work out for another hour, have a glass of wine, soak in the tub, sleep and then six hours later was back on set. I’m not complaining, that’s just regular Hollywood stuff.” She remembers staging a coup on set after she noticed several crew members falling asleep on their feet.

She’d seen an overworked crew member die in a car accident after falling asleep at the wheel whilst making Point Break, and she knew she could make the production halt if she stuck by the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) rules of only allowing members to work 12-hour shifts, or getting paid overtime. She didn’t want the overtime money, she just wanted the crew to sleep. However, she didn’t get involved with the daily studio battles: “I wasn’t a producer or a writer at that time. So I didn’t. I knew they were going through it but I didn’t get involved at the time. Maybe I should’ve. But I didn’t.”

Tank Girl’s creators Hewlett and Martin did not have a great time with the making of the film, and the adaptation has since remained a sore subject. In 2011, Martin recalled: “Unfortunately they tried to make it look cool. They argued over what was cool and what wasn’t cool. When you go to Hollywood and you see a bunch of fat businessmen sitting in offices arguing what’s cool, you just think, ‘No mate. Whatever you are going to come up with you’re wrong.’ The struggle just ripped the heart out of the film and ended up not looking like anything really.”

Petty remembers them fondly, they were on set occasionally and at the end of the shoot, Hewlett gave her a signed and framed original of her favourite image from the Tank Girl comic books. In the image, Tank Girl is plopped atop a water buffalo, a cigarette loosely hanging from her lips, sleeping, and it reads: “Sometimes when I’m asleep I dream that I can fly. It’s not really flying sometimes I dream that I’m running away from the army down past the pub near Stevie’s House… and I start leaping, over rocks and bushes, and then I feel my heart kind of tugging upwards and I put my arms out like wings… and raise my legs up to my chest like undercarriage… then I just glide along… leaving the army behind me… god I’m fucked.”

Everyone involved in the film has been consistent in blaming the studio interference for a messy final product and lackluster release. Talalay called Tank Girl her favorite film to direct in an interview, “until the studio intervened in their useless wisdom about the ‘morality of America’.”

The final nail in Tank Girl’s coffin was the rating. The film was rated R in the United States. This meant that its distribution potential was limited, only allowing it to be shown to audiences over the age of 17. An R rating meant that the film’s core audience, teenage girls, couldn’t legally go see it. The huge impact that the MPAA’s rating system has on films, particularly on independent films, and particularly on films depicting sexuality, is well-documented and subject to a thoroughly fascinating documentary This Film Is Not Yet Rated (2006). Of course, a film about a foul-mouthed, dirty-minded, burping, farting punk with ever-changing hairstyles wouldn’t be ‘appropriate’ content for teen girls.

It’s often forgotten that Tank Girl was a fairly big budget, commercial project. It had a massive campaign, with premieres in Los Angeles and London. The publicity team asked Petty at the time what cinema she’d like to see the premiere happen at, a theatre that had some meaning to her. She chose the Chinese Theatre, a true movie palace where countless movie premieres have taken place. “It’s the dream,” Petty remembers. “When I was in high school in Iowa, I was drawing pictures of the Chinese Theatre. It’s the pinnacle of success.” It was packed, her mom and her sisters flew in for the premiere, Commes des Garçons lent her a stunning outfit. It was so packed that in order to get to the after-party at the hotel across the street, Petty had to be carried on the shoulders of the security guard.

It was on the premiere’s red carpet that she first saw her co-star Ice-T (who plays the leader of the Rippers, T-Saint) in the flesh, without the layers of prosthetics and make-up on him. The London premiere of Tank Girl was at the Roundhouse, and “the nice English boys” (that’s Hewlitt and Martin) took her to all the good clubs and parties while she was there. The promotional tour that followed was gruellingly intense. “One day I had breakfast in Paris, lunch in Rome and dinner in London,” Petty reminisces. There was a lot of hype behind the release. She was doing press, Q&As, signings. There was a clothing line with t-shirts, dog tags, posters and more.

Tank Girl was rated R (which, in the US market, means that any children under 17 need to be accompanied by an adult). Petty was furious about the rating. Tank Girl was released on the same weekend as Tommy Boy, the Chris Farley-David Spade fronted comedy, which grossed $8 million in its first weekend. Meanwhile, Tank Girl, which opened in 1,341 theatres across the US, grossed just over $2 million in its first weekend. It would end up grossing just over $4 million domestically and was considered a box office flop. Petty went around theatres in Los Angeles, dropping in to see the crowds in theatres and was convinced that people bought tickets for Tommy Boy to sneak into Tank Girl. It does beg the question what it was about Tank Girl that merited the R rating. The violence is cartoonish, there isn’t any actual sex, and – alas – zero Ripper penis. “I killed people in it,” Petty said, “but there wasn’t any blood, it was cartoon violence! But it was because it was about a woman talking shit.”

It took a while for Petty to shake off Tank Girl after the shoot wrapped. Weeks after the shoot had ended, she’d had had recurring sensations, sort of memories that she couldn’t quite catch, a thought that she couldn’t quite grab. She ended up going to a psychiatrist.

'What do you do for a living?' she asked, and I told her. 'What was your last job?' and I told her Tank Girl. 'What did your character do?' Well, she lives in the future and there's no water. She's married to a kangaroo. And she's tortured by this evil Malcolm McDowell, you know, the guy from A Clockwork Orange. I'm put in a freezer in my underwear and tortured. I'm hung upside down in a tube and they try to drown me to death. And she's like 'okay, stop.' And the psychiatrist said: 'you actors are so stupid.' - Lori Petty.

The next time it happens, she got told, say this to your brain: “Thank you so much, we’re not doing that right now.” And it worked.

Tank Girl was full of promise. It was Rachel Talalay’s first big-budget action studio movie. It was Lori Petty’s big star-making role. “I really thought I’m going to break the glass ceiling and there’s going to be success for women in action [movies],” said Talalay in 2014.

It wasn’t.

But that doesn’t mean it did not have an impact. Petty started noticing women cosplaying Tank Girl at conventions: “Twelve-year-olds, 15-year-olds, 50 years olds dressed as Tank Girl. I’m so impressed by them,” says Petty. “They’re technicians. If I see someone in a Tank Girl helmet, I have to sign it! It’s imperative!” She kept a lot of the props, outfits and memorabilia from the making of Tank Girl- but it was all lost in an arson attack on her storage unit while she was shooting Orange is the New Black. The Tank Girl merch continues getting sold out, consistently. A couple of times a year, Petty will buy t-shirts, magnets, and other merch from the official Tank Girl store (“stuff I had a thousand years ago.”) And every time she does that, she laughs, she gets a refund and an email saying ‘Can you stop doing that! Just email us if you want anything.’

There is a particular flavour of ‘90s weirdness that is impossible to name and impossible to replicate now. It’s a genuine meld of camp sensibility, a winking humour layered with double entendres and timelessness. Films like The Addams Family (1991), Men in Black (1997), Beetlejuice (1988) and, of course, Tank Girl exist in their own particular universe, partially divorced from the era in which they were made. They walk a fine line between campiness and earnestness.

Tank Girl was the first true unruly female anti-hero. There hasn’t really been such a powerful, no-holds-barred riotous female character on screen until very recently. Tank Girl walked so Harley Quinn could run. To no one’s surprise, Margot Robbie’s production company has now optioned the rights to make a new Tank Girl adaptation. In Talalay and Petty’s hands, she deviated from the comic books but became her own, unique blend of madness, humor and sexiness. Petty says it best: “She doesn’t need to fit into a system. She’s her own system.”

This article was originally published on March 7, 2021 on the original Companion site.

The cost of your membership has allowed us to mentor new writers and allowed us to reflect the diversity of voices within fandom. None of this is possible without you. Thank you. 🙂